Management of Superficial Fungal Infections

Peter C. Schalock

Arthur J. Sober

Although they are neither dangerous nor life threatening, superficial fungal infections are prevalent, irritating, and often recurrent. They are easily diagnosed but commonly confused with nonfungal dermatoses such as impetigo (see Chapter 184) and nummular eczema. The primary care physician and other health care professionals encountering such patients should be capable of providing a definitive diagnosis, cost-effective therapy, and patient education for prevention.

Most of the organisms that cause superficial fungal infections are ubiquitous in nature. Fungal infection occurs when one of these ubiquitous organisms invades the superficial layers of the skin. Hereditary factors and systemic diseases like diabetes commonly contribute to susceptibility, as do local precipitants such as dampness and friction leading to skin maceration. Dermatophytes do not usually invade below the level of keratin. Dermatophytic and candidal infections produce scaly, erythematous lesions with defined margins; multiloculated bullae may occur, especially on the feet. Characteristic presentations vary depending on the organism and area of the body involved.

Tinea Versicolor

Tinea versicolor, caused by Malassezia globosa and other Malassezia species, produces brown, pink, red, or white scaly patches or slightly elevated plaques on the chest, back, and shoulders. During the summer, it may present as areas of hypopigmentation often mistaken for vitiligo. Decreased pigmentation results from the inhibition of melanocytes by dicarbonic acids produced by the yeast. Scratching a macular area raises a small amount of fine scale, suggesting the diagnosis. Examination of the skin with a Wood light reveals gold or orange-brown fluorescence. The infection is confirmed by scraping a scaly lesion and examining it with a drop of 20% potassium hydroxide for characteristic short hyphae and spores, sometimes referred to as spaghetti and meatballs.

Dermatophyte Infections

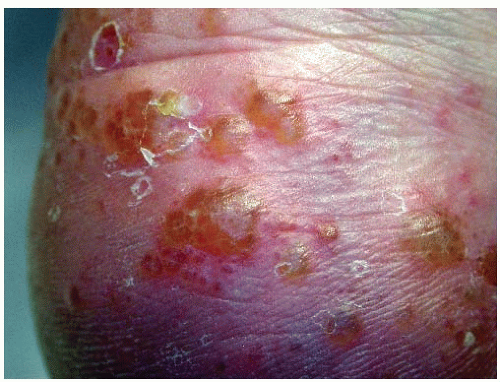

Dermatophyte infections are defined by the area of the body they affect. The most common is tinea pedis. This condition is characterized by blisters and/or inflammation and scale on the soles and interdigital areas of the feet (Figs. 191-1 and 191-2). Tinea cruris involves the groin and inner thighs and sometimes even extends onto the abdomen and buttocks. Tinea corporis affects other areas of the body, including the trunk and extremities; facial involvement is referred to as tinea faciei. Tinea capitis, or scalp ringworm, occurs almost exclusively in children. Tinea barbae, involving the bearded area, is uncommon but needs

to be considered in the differential diagnosis of a facial rash. Onychomycosis, caused by Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum, leads to characteristic accumulation of subungual keratin, which produces a thickened, distorted, crumbling nail. Microsporum canis, acquired by contact with infected pet cats and dogs, is another common pathogenic fungus.

to be considered in the differential diagnosis of a facial rash. Onychomycosis, caused by Trichophyton rubrum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum, leads to characteristic accumulation of subungual keratin, which produces a thickened, distorted, crumbling nail. Microsporum canis, acquired by contact with infected pet cats and dogs, is another common pathogenic fungus.

Atypical presentations may be noted. The treatment of a superficial fungal infection with a topical corticosteroid can suppress inflammation without curing the infection, a state referred to as tinea incognito. The infection of the hair follicle by a dermatophyte is called Majocchi granuloma (Fig. 191-3). It is caused by T. rubrum infection and is most commonly seen on the legs of women. It is hypothesized to be from shaving of the legs. The fungal infection penetrates the hair shaft and causes an inflammatory/granulomatous response. Kerion is a vigorous inflammatory response to fungal infection of the scalp, frequently caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. A boggy, tender plaque forms on the scalp, often with lymphadenopathy. Permanent alopecia may occur in long-standing areas of involvement.

Candida Infections

Candida infections of the skin occur principally in intertriginous locations, such as the axillae, groin, intergluteal folds, inframammary area, and interdigital web spaces. Crusted involvement of the orolabial commissures, known as perlèche, and involvement of the glans penis also occur. The presence of erythema on the glans penis and scrotum suggests a candidal rather than a dermatophyte infection. Lesions may be pustular and thin walled, located on a reddish base, and often produce burning and itching. Candidiasis may be clinically suspected by the presence of characteristic smaller satellite lesions (papules, macules, or pustules outside the margin of the primary lesion) (Fig. 191-4).

The finding of scaly, erythematous lesions with defined margins in characteristic areas of the body that promote the growth of fungi should raise suspicion of a superficial fungal infection. Satellite pustules suggest a candidal involvement. In intertriginous areas, fungal infection must be differentiated from intertrigo and erythrasma. Asymptomatic, slightly erythematous to light brown, finely scaling patches in the groin and upper thigh with little or no central clearing are characteristic of erythrasma (a corynebacteria infection). Early intertrigo is characterized by slight maceration and erythema. With time, the redness becomes more intense, and the epidermis becomes eroded or even denuded. Psoriasis involving the nails may lift the nail and mimic onychomycosis, but pitting is not seen with fungal infection; skin involvement with psoriasis can lead to erythematous scaling plaques and be mistaken for fungal dermatitis, but prime areas of involvement (e.g., extensor surfaces) are quite different from those of fungal dermatitis.

Potassium Hydroxide Testing

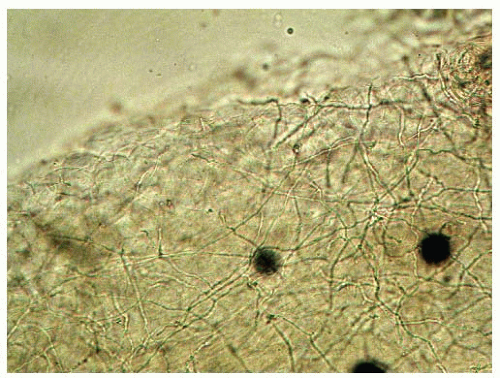

When dermatophyte infection is suspected, microscopic examination of scrapings from an involved area of skin is helpful. To prepare a specimen for microscopic examination, the border of the lesion is scraped lightly with a no. 15 scalpel blade or the edge of a microscope slide. The scale is collected onto a clean microscope slide, and a cover slip is used to push all the scale into a small mound. Several drops of 20% potassium hydroxide solution are placed in the center of the mound of scale, and a cover slip is laid over it. The slide must be heated lightly to improve “clearing” of the epithelial cells.

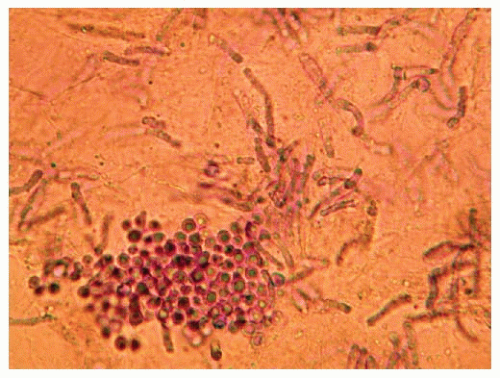

Under a magnification of 40× with reduced light and a narrow aperture, threadlike hyphae can be seen crossing cell walls (Fig. 191-5). The presence of branched, septate hyphae can be confirmed by using higher power (100×) to make sure that artifacts are not being mistaken for hyphae. If budding spores and pseudohyphae are found, the diagnosis is candidal infection. Short hyphae and spores suggest pityriasis versicolor (Fig. 191-6). The wet mount should be examined within a few hours. The hyphae will dissolve after a period of time. Occasionally, a scraping must be planted on Sabouraud dextrose agar for culturing to identify the fungal infection.

If candidal infection is identified or topical fungal infection is recurrent or extensive, one should check for conditions associated with immune compromise (e.g., HIV infection, diabetes, cirrhosis, lymphoma, steroid use, chemotherapy).