Introduction

While the majority of adults will have suffered from back pain at some point in their life, it is usually a minor self-limiting condition. Pain in the lower back is extremely common: around 60% of the adult population can expect to have a back problem at some time in their life. Although most back pain is generally benign a significant percentage of the population will develop chronic pain and disability (Box 5.1). The vast majority of adults with low back pain are labelled as having ‘mechanical low back pain’, which implies that there is a problem with the mechanism of the back for which a generic treatment package is probably appropriate in the first instance.

- 3–4% of young adults (below are 45) are chronically disabled by low back pain

- 5–7% of older adults (45+ years) are chronically disabled by low back pain

The mechanical problem may be structural (e.g. disc pathology, facet joint arthropathy), but frequently is a ‘mechanical dysfunction’, where the normal mechanism is disturbed. Recognising this possibility (dysfunction vs. pathology) is central to managing patients and their expectations. With some persistent chronic pain states the recognition that the functional disturbance is central may require a further shift in our treatment paradigm.

Mechanical Dysfunction

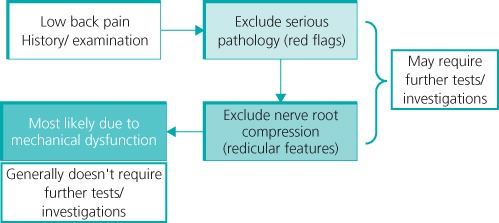

The most important first step in management of a patient with back pain is to rule out serious pathology without unnecessary investigations (Figure 5.1). Low back pain is a symptom not a disease. The main thrust of medical education is to recognise pathology, so when we are presented with a symptom (low back pain) that has a low probability of having a pathological basis we may struggle to deal with our uncertainty and possibly patient demands for scans (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Common features associated with mechanical low back pain compared to nerve root pain

| Mechanical back pain | Nerve root pain |

|

|

Start by considering the ‘red flags’ – pointers to possible pathology that may indicate the need for investigation (Box 5.2).

- Age <20 or onset >55 years

- Trauma

- Constant, progressive, non-mechanical pain

- Previous history of carcinoma, systemic steroids, drug abuse, HIV

- Systemically unwell/weight loss

- Persisting severe restriction of lumbar flexion

- Widespread neurology

- Structural deformity

- Cauda equine syndrome

- Inflammatory pain – night pain, morning stiffness

Guidelines

Many back pain guidelines have been published in several countries. Generally, the content of these guidelines is similar. The Cochrane Back Group has reviewed the published evidence for many aspects of back pain. In general, there is a paucity of high quality, well designed trials, often making it difficult to evaluate truly the effectiveness of various therapies. Several guidelines focus on acute low back pain (up to an arbitrary 12 weeks). In the United Kingdom further guidelines were published by The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in 2009 specifically for the patient group with persistent back pain from 6 weeks to 12 months (http://www.nice.org.uk/CG88). For example, surgical intervention for appropriately selected patients suffering from lumbar disc prolapse with radicular features does reduce the acute attack more quickly than conservative management, but may have a limited effect on the long-term natural disease history (Table 5.2).

Table 5.2 Suggestions for diagnosis and treatment of low back pain

| Summary of recommendations for diagnosis of low back pain | Summary of recommendations for treatment of low back pain |

|

|

Investigations – How Valuable is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)?

Plain radiographs of the lumbar spine have a limited role (unless there is a ‘red flag’ indication), and all published guidelines recognise this. However, there may be an expectation from patients that an MRI scan is necessary to assess their problem and there may be some pressure to refer for this. Unless there is nerve root pain an MRI scan is unlikely to be helpful. The high rate of abnormal findings in both discs and joints in the normal population makes the interpretation of any positive results problematic (Figure 5.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree