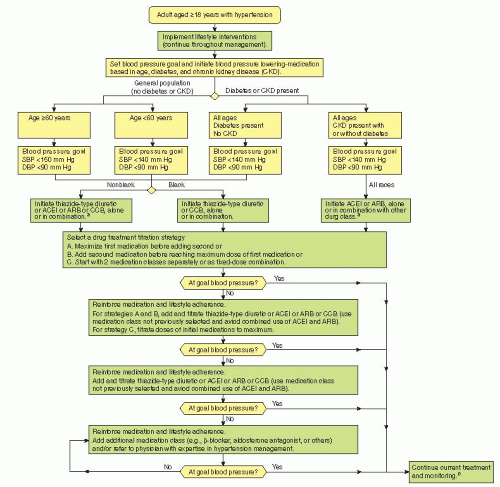

When to Initiate Drug Therapy

Pharmacologic measures require consideration when comprehensive lifestyle measures prove inadequate or when overall cardiovascular risk is high (

Fig. 26-1 and

Table 26-3). Persons with stage 2 hypertension, target organ damage, diabetes, or multiple cardiovascular risk factors (especially diabetes), and chronic kidney disease should be given consideration for pharmacologic therapy at the outset. For others, pharmacologic treatment can usually be deferred for weeks to months while the lifestyle modifications previously enumerated are instituted. If blood pressure does not normalize within 6 months, pharmacologic therapy should be initiated. Patients at the lowest level of risk (e.g., age <50 years, stage 1 disease, no diabetes, no chronic kidney disease, and no other cardiovascular risk factors or signs of target organ involvement) can probably delay pharmacologic therapy for 6 to 12 months while nonpharmacologic measures are tried (

Fig. 26-1 and

Table 26-1). On the other hand, pharmacologic therapy in

elderly patients with

isolated systolic hypertension should not be ignored, because patients older than 50 years of age have, as noted, a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular complications, which can be markedly reduced with drug

treatment. In JNC 8, the blood-pressure threshold for initiation of pharmacologic therapy in the general population 60 years and older has been raised to 150/90 mm Hg on the basis of seminal studies in the elderly.

Pharmacologic therapy for essential hypertension remains largely empiric, guided in part by results of major prospective trials and a few generalizations about underlying mechanisms (e.g., sodium retention is common in the elderly and African Americans). Rapid advances in pharmacogenetics hold promise for a much more targeted and individualized approach to prescribing by improving the detection of underlying mechanisms and genetic polymorphisms that determine disease course and drug response (e.g., the α-adducin gene variant associated with salt-sensitive hypertension and response to diuretics).

In the meantime, consensus recommendations (based on largescale, long-term randomized trials demonstrating significant reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality) remain the best guides to drug selection. JNC 8 recommends for the general nonblack population (including those with diabetes) first-line treatment with a thiazide diuretic, calcium-channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), or angiotensinreceptor blocker (ARB), either alone or in combination. Major studies (e.g., ACCOMPLISH ALLHAT) suggest flexibility is warranted in selection of the initial agent, with any of these first-line agents a reasonable choice, refined by attention to patient characteristics. In black patients, including those with diabetes, JNC 8 notes evidence supporting initial therapy with a thiazide diuretic or a CCB. In those with chronic kidney disease, an ARB or ACEI is recommended for initial and add-on therapy. Ultimately, most patients require two or more drugs for adequate control, particularly those at heightened cardiovascular or renal risk.

The first-line drugs are comparable in efficacy. In a head-to-head, long-term, large-scale, prospective, randomized study (ALLHAT), the thiazide-like diuretic chlorthalidone proved just as effective as ACEI therapy (lisinopril) and CCB treatment (amlodipine) in reducing rates of fatal coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, and all-cause mortality. In addition, diuretic therapy was superior to amlodipine in lowering the risk of heart failure and better than lisinopril at reducing the risks of heart failure, stroke, and combined forms of cardiovascular disease. Results were consistent across racial groups, with no significant differences in outcomes for blacks compared to nonblacks as regards benefits from thiazide-like diuretics compared to other first-line agents. ALLHAT also uncovered an unappreciated increase in risk of heart failure in older men taking the previously recommended first-line α-blocker agent doxazosin.

Beta-blockers had previously been considered first-line therapy for hypertension, but Cochrane review found no reduction in all-cause mortality. Nonetheless, reductions in rates of cardiovascular events have been noted, suggesting consideration of use in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk or ongoing cardiovascular disease. Regardless of the medical regimen selected, all nonpharmacologic measures should be continued because they enhance the effectiveness of drug therapy and allow for the use of fewer medications at lower doses.

As long as there is a partial response to initial therapy, the dose of the first agent should be increased as necessary and as tolerated to achieve the desired blood pressure. If there is an initial response but target blood pressure has not been achieved, the dose may be further increased or a low dose of an agent from another first-line class can be added. However, if there is no response to the initial dose, then switching to a drug from another first-line class is recommended rather than adding a second agent. Although monotherapy suffices in some cases, most patients will require two or more medications to reach the goal. If thiazide is not the first drug, it should almost always be the second agent used because it enhances the effectiveness of all other antihypertensive agents, particularly in blacks. An ARB or ACEI should be added if not already started in persons with chronic kidney disease.

Cost Containment

Primary care physicians must consider affordability in the design of the antihypertensive regimen. Without attention to cost, the financial burden of a lifelong pharmacologic program can easily become so great that patients fill only part of a prescription or cut frequency or dose, compromising compliance and threatening blood pressure control. Fortunately, most thiazides and ACEIs are now available generically at much reduced cost, as are many CCBs and an increasing number of ARBs.

The reaffirmation of the effectiveness of generically available first-line agents in randomized, prospective, head-to-head study should help to control the cost of treatment. Their very low cost, ease of use, and excellent efficacy across a wide range of patients make them an essential consideration for every hypertensive treatment program. Additional approaches to minimizing cost include substituting a sustained-release preparation if it is less expensive than a multidose regimen; staying with a less-expensive, older antihypertensive agent if it is reasonably effective and well-tolerated; and using the lowest dose possible.

Maximizing Compliance

Maintaining as simple a program as possible facilitates compliance, with the best rates seen for programs that require a limited number of pills taken once or twice daily. Cost is also an essential consideration but becoming less of a factor with the conversion of most antihypertensive drugs to generic formulations. A host of interventions have been recommended. Randomized trials find that home monitoring of blood pressure and behavioral coaching by nurses can be helpful, particularly for persons with inadequately controlled hypertension. Combination approaches appear best, but there is some decay over time in the effect of behavioral coaching.