Management of Breast Cancer

Irene Kuter

In the 18th century, breast cancer was a rare disease. It is now one of the most common malignancies in the United States. There are more than 230,000 cases diagnosed in the United States per year and over 39,500 deaths. One in eight women in the United States today will eventually be diagnosed with breast cancer. Unfortunately, despite major advances in the treatment of breast cancer and a trend toward increased survival over the last decade, approximately 25% of women who develop the disease will eventually die from it. Given the prevalence of breast cancer and the multidisciplinary approach to its treatment, which involves not only the oncology team but also the primary care practice, the primary care physician and medical home team need to be knowledgeable about basic elements of management. This chapter focuses on key management issues. Screening and evaluation are the subjects of separate chapters (see Chapters 106 and 113).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY, CLINICAL PRESENTATION, AND COURSE (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 and 31)

Risk Factors

Lifestyle

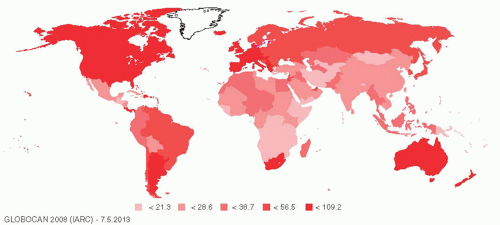

A glance at the world map (Figure 122-1) shows that the incidence of breast cancer is highest in “Westernized” countries, where women tend to mature earlier, delay childbirth, have fewer children, breast-feed less frequently, and go through menopause at a later age than do their counterparts in the less-developed world today or in the United States in the 18th century. Women in Westernized countries are also more likely to be obese. It seems likely that the variation in breast cancer incidence is largely related to these lifestyle differences. There are, of course, many other theories that have been put forward to explain the high incidence of breast cancer in the Westernized world, including higher exposure to chemicals such as herbicides, pesticides, and plastics, many of which have estrogenic properties. In addition, there is an intriguing theory that low vitamin D levels may substantially increase the risk of breast cancer. There are some major risk factors for breast cancer that are important for the primary care physician to recognize.

Exposure to Ionizing Radiation.

Radiation to the breasts at a young age is a major risk factor. Women who had mantle radiation for Hodgkin disease when they were younger than 25 should be recognized as high-risk individuals. Women who underwent repeated fluoroscopy for TB or because of scoliosis, at a young age are also at increased risk, as are women who had radiation in childhood for such conditions as thymic hyperplasia or acne.

Breast Density and Histology

Women with a history of atypical ductal hyperplasia or lobular neoplasia (also known as lobular carcinoma in situ [LCIS]) are also at increased risk for developing breast cancer. Women with extremely dense breasts also have an increased risk, and some states have passed legislation that women who have very dense breasts should be informed of this so that they will be aware that screening with mammography alone may not be sufficient.

Gene Mutations: BRCA1 and BRCA2

Although the majority of breast cancer cases are thought to be sporadic, it is generally accepted that between 5% and 10% of breast cancers are caused by a genetic susceptibility that can be traced to a highly penetrant gene. The most common genetic mutations affecting breast cancer risk occur in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. In the general population, these mutations affect one in several hundred individuals, but in the Ashkenazi Jewish population the carrier rate is 2.5%. On average, inheritance of a deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 confers a 60% to 85% lifetime risk of breast cancer, and a 40% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer, on the affected individual.

Red flags in a family history for a significant BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation include early-onset breast cancer (women in their 20s or 30s), male breast cancer, bilateral premenopausal breast cancer, and a family history of ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history should be referred for genetic counseling.

There are other high-penetrance, low-frequency genes that can increase breast cancer risk, but at present it is not practical to screen for these routinely. There are many other genes with low penetrance that are more frequent in the population, and how much these affect risk is not clearly known at present.

Clinical Presentation

The median age at the time of diagnosis of breast cancer is about 55 years. However, 20% of breast cancers occur in women younger than 40 years of age, and about 10% of these younger women are pregnant at the time of diagnosis. Breast cancer rarely occurs among men; about 2,000 such cases are diagnosed annually in the United States. Stage at time of diagnosis has important consequences for prognosis (see Table 122-1). Early-stage breast cancer encompasses both stage 0, which is noninvasive, and stages I and II of invasive disease.

Noninvasive Disease: Stage 0 (Carcinoma In Situ)

Noninvasive cancer, carcinoma in situ, is characterized as ductal (DCIS) or lobular (LCIS) based on histology and growth patterns. These two lesions have very different characteristics.

DCIS arises as a focal lesion within the breast, often in a background of atypical ductal hyperplasia, and has the potential to

develop into an invasive ductal cancer. It is commonly detected early because of associated tiny clustered microcalcifications that form within the duct at the site of cell death. When there is a recurrence in the breast after lumpectomy for DCIS, the recurrent cancer is invasive 50% of the time; however, recurrence in the breast generally does not compromise survival, and lumpectomy followed by radiation is generally the standard of care. DCIS accounts for 20% of all newly diagnosed breast cancers in the United States and over 30% of cancers detected by mammography. Clearly, it would be helpful to know which of the DCIS lesions are likely to become invasive and which not, so that not every woman would need to undergo surgery and radiation therapy. Research studies are looking into this.

develop into an invasive ductal cancer. It is commonly detected early because of associated tiny clustered microcalcifications that form within the duct at the site of cell death. When there is a recurrence in the breast after lumpectomy for DCIS, the recurrent cancer is invasive 50% of the time; however, recurrence in the breast generally does not compromise survival, and lumpectomy followed by radiation is generally the standard of care. DCIS accounts for 20% of all newly diagnosed breast cancers in the United States and over 30% of cancers detected by mammography. Clearly, it would be helpful to know which of the DCIS lesions are likely to become invasive and which not, so that not every woman would need to undergo surgery and radiation therapy. Research studies are looking into this.

LCIS is not a focal lesion but rather a form of atypical hyperplasia of the lobules that can diffusely affect both breasts. It does not give rise to calcifications and is usually discovered as an incidental finding on a biopsy performed for some other reason. Although not a cancer, it is thought to be a marker for increased risk of invasive disease (which may be ductal or lobular) anywhere in either breast. The incidence of invasive cancer in women with LCIS is about 1% per year.

Early Invasive Disease: Stages I and II

These stages designate relatively early forms of invasive breast cancer:

TABLE 122-1 Breast Cancer Stage at Presentation and Prognosis | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Stage I disease—primary tumor is less than 2 cm in diameter, and there is no axillary lymph node involvement.

Stage II disease—primary tumor is 2 to 5 cm, or there is involvement of (nonmatted) axillary lymph nodes.

Approximately 60% of patients with invasive primary breast cancer now present with stage I disease, thanks to improved mammographic screening.

Advanced Disease: Stages III and IV

These stages are characterized by more extensive locoregional primary tumor or the presence of metastases.

Stage III disease—extensive tumor (>5 cm) at the primary site, extension of the primary tumor to the chest wall or skin, or matted axillary lymph nodes

Stage IV disease—distant metastases

For women with early-stage breast cancer, prognosis (in the absence of systemic therapy) has traditionally been estimated based on the size of the primary tumor and the number of positive nodes. The best source for estimating prognosis has been the meta-analyses of the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). An online tool (Adjuvant!) for estimation of individual prognosis has been developed largely based on statistics from this work. Tumor size and grade, receptor status, and number of involved lymph nodes are key determinants.

By Stage of Disease

For women with negative nodes, 10-year cumulative systemic recurrence rates for tumors smaller than 1 cm, 1 to 2 cm, and 2 to 5 cm in diameter are approximately 20%, 30%, and 50%, respectively. Among women with a primary tumor 2 to 3 cm in size who also have one to three positive nodes, over 60% have a recurrence within 10 years. For women with a tumor of the same size but four to nine nodes positive, the 10-year recurrence rate is almost 80%. For women with more than nine nodes positive or with stage III disease, long-term recurrence-free survival is less than 10%. Inflammatory breast cancer (invasion of tumor

into dermal lymphatics with peau d’orange changes from dermal edema) has a worse prognosis than noninflammatory lesions, but fortunately with multimodality therapy, 30% to 40% of these women are now cured.

into dermal lymphatics with peau d’orange changes from dermal edema) has a worse prognosis than noninflammatory lesions, but fortunately with multimodality therapy, 30% to 40% of these women are now cured.

By Receptor Status

In addition to the stage of tumor and tumor size, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status affect the prognosis. Patients with stage I or stage II disease whose tumors have estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, or both have longer disease-free survival (DFS) than do those with the same stage of disease whose tumors are hormone receptor negative, though the DFS curves tend to merge with longer follow-up. Positive receptor status is also predictive of a positive response to antiestrogen therapy.

Other receptor markers also have prognostic and predictive value. Amplification of human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2, also called HER2/neu or erbB2) with overexpression of its product at the surface of cancer cells occurs in about 15% to 20% of breast cancer cases and is associated with a poorer prognosis. As discussed later, HER2 amplification or overexpression is predictive of therapeutic response not only to the monoclonal antibody against HER2 developed for that purpose but also to certain chemotherapy regimens, so that the prognosis, with appropriate therapy, of HER2-positive breast cancer is now much more favorable.

By Presence of Metastases

Breast cancer may metastasize to almost any site in the body, but the most common sites are bone, liver, lungs, and pleura. The majority of patients with metastatic breast cancer will respond to therapy, but only a few (perhaps <10%) show complete regression, and fewer still survive 10 years.

Metastatic lesions may develop after a long period of apparent freedom from disease, even longer than 20 years. The mechanism of this so-called tumor dormancy is a subject of current research. Five years without evidence of metastatic spread does not indicate cure. This is especially true for the lowergrade ER+ PR+ HER2- cancers, whereas if the HER2-positive and triple-negative cancers are going to recur, they usually do so in the first 5 years of follow-up.

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT (33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 and 69)

Diagnosis is usually made with a stereotactic core or fine needle aspirate of a suspicious lesion under mammography or ultrasound guidance. Upon confirmation, patients should be fully informed, promptly staged, and advised of their therapeutic options before definitive treatment is undertaken. In most major medical centers in the United States, the approach to treatment of breast cancer is multidisciplinary. As soon as a diagnosis has been made, a woman will meet with a team consisting of a breast surgeon, a medical oncologist, and a radiation oncologist. Usually, a breast radiologist and breast pathologist will be available to review imaging and pathology. Genetic counselors, research staff, and social workers may also be in attendance. In this “one-stop shopping” approach, a woman may be educated about her own particular cancer and advised on the optimal approach and sequence of treatments to be offered.

Accurate staging is essential to planning the appropriate treatment.

Axillary Lymph Node Biopsy

Sentinel lymph node biopsy has largely replaced full axillary lymph node dissection. This more limited, less morbid procedure involves injection of radionuclide tracer at the site of the primary tumor, followed by scintigraphic scanning to identify the first draining lymph node, which is then resected and examined pathologically. Frequently, blue dye is also used to help identify the sentinel node. Accuracy of sentinel lymph node mapping is greater than 95%, with a false-negative rate of approximately 5% to 8%.

In the past, if the sentinel node was positive for malignancy, the remainder of the axillary nodes were then resected for examination, but patients with a negative sentinel lymph node were spared the procedure. More recently, the need for axillary lymph node dissection has been questioned even for women with a positive sentinel node in the setting of a clinically negative axilla. In a landmark trial of women with a positive sentinel lymph node randomly assigned to either axillary node dissection or no dissection, with both groups getting axillary radiation therapy, there was no significant difference in axillary recurrences, DFS, or overall survival.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree