Risk factors

Age

Female gender

Pregnancy

Obesity

Bariatric surgery due to rapid weight loss

Ileal resection

Hypertriglyceridemia

Cirrhosis

Ethnic groups

Pima Indians and other Native Americans

Hemolytic disorders

Sickle cell anemia

Hereditary spherocytosis

Medications

Ceftriaxone

Octreotide

Oral contraceptives

Gemfibrozil and other fibrate anti-hyperlipidemic agents

Gallbladder stasis

Diabetes mellitus

Total parenteral nutrition (TPN)

Pathophysiology

Gallstone formation is directly related to the relative concentrations and solubility of bile contents, most notably cholesterol. Biliary “sludge” is a term used to describe a combination of cholesterol crystals, calcium bilirubinate, and mucin that congeals and acts as a precursor to stone formation. This sludge along with gallbladder dysmotility promotes the development of gallstones. Gallstones are classified as either cholesterol or pigment stones, and the particular classification depends on the relative cholesterol content. Cholesterol stones are composed mainly of cholesterol crystals as the name suggests and are due to an increased saturation of biliary cholesterol, a decrease in bile salts, and/or biliary stasis. Pigment stones can be further categorized as black or brown stones. Black pigment stones occur in those with conditions that result in high concentrations of unconjugated bilirubin. The primary composition of black pigment stones is calcium bilirubinate. Common etiologies include hemolytic disorders (e.g., sickle cell anemia) or changes in the enterohepatic circulation (e.g., Crohn disease, ileal resection, and cystic fibrosis). The third type of gallstone is the brown pigment stone, which results from hydrolysis of conjugated bilirubin or phospholipid by bacteria. This type of stone occurs in patients with infections of the biliary tract or strictures. Brown pigment stones have also been found as primary common bile duct stones.

Cholesterol stones comprise the vast majority of gallstones (75 %), especially in industrialized countries, with black pigment stones less frequently seen (20 %), and brown pigment stones being least common (5 %) [7]. Black pigment stones occur more prevalently in communities with higher frequencies of hemolytic disorders, and while rare in Western culture, brown pigment stones arise more commonly in Asian populations.

Several pharmacologic agents that are associated with the formation of gallstones have been identified. In children, intravenous ceftriaxone has been well documented, although the majority of patients remain asymptomatic [8–10]. In symptomatic patients, clinical improvement is generally seen with discontinuation of the medication [11–14]. Another drug known to contribute to gallstones is octreotide. Among its most common side effects is biliary tract pathology, including sludge or gallstone formation and ductal dilatation [15, 16]. Dysmotility of the gallbladder and decreased secretion of bile have been documented, even after administration of a single dose, and the risk of such side effects is proportional to the duration of therapy [17]. Lastly, gemfibrozil and other fibrate antihyperlipidemic agents have been associated with gallstones as the mechanisms of action of these agents increase cholesterol excretion through bile, promoting increased biliary cholesterol concentration [18].

Clinical Presentation

Cholelithiasis can be classified as asymptomatic or symptomatic. Asymptomatic patients are defined as those with known gallstones—usually discovered incidentally—but without associated symptoms, termed asymptomatic cholelithiasis. Patients are deemed symptomatic if they experience the typical pain related to gallbladder disease, often referred to as “biliary colic.” The pain is described as constant, epigastric and/or right upper quadrant abdominal pain that usually resolves after several hours, occurs characteristically post-prandially, and is associated with nausea and vomiting [19].

As opposed to asymptomatic cholelithiasis, patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis are at an increased risk for developing complicated gallstone disease, including acute cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis and/or cholangitis, and gallstone pancreatitis. A randomized, prospective study showed that in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis, 38 % per year experienced recurrent pain attacks and 2 % per year required cholecystectomy for significant biliary symptoms [20].

On the other hand, most patients with gallstones (up to 70 %) remain asymptomatic [21]. Of those with incidental (asymptomatic) gallstones, only 20 % will experience symptoms over a 15-year time point, and even then, their initial symptoms are normally biliary colic-type pain, rather than severe complications of gallstone disease [22]. Rarely does a patient with no symptoms experience complicated gallstone disease on first presentation. Risks for symptoms or complications from initially asymptomatic cholelithiasis are reported in the literature to be 1–4 % per year [23, 24]. Interestingly, one retrospective cohort analysis with propensity score matching found patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) to be significantly more likely to develop gallstone-related symptoms or complications than patients without CAD. The finding suggests that patients with CAD be monitored more closely than other patients with gallstone disease [25].

Diagnostic Imaging

Individuals with silent gallstones do not undergo routine diagnostic imaging for this condition since, by definition, they are asymptomatic and therefore are unaware of the presence of stones. As such, gallstones in those without symptoms are usually detected as an incidental finding on abdominal imaging done for unrelated reasons. Below is a summary of different modalities used to assess the gallbladder and biliary tract.

Plain Abdominal Radiographs

Plain films of the abdomen are of little use for evaluating the gallbladder and bile ducts. In very rare circumstances, one may be able to identify pneumobilia (air in the biliary tract), which can signify a cholecystoenteric fistula. Additionally, the majority of gallstones are not radiopaque, and therefore will not be visualized on plain radiographic imaging. Only occasionally will stones or the gallbladder wall be calcified enough to be seen on plain radiographs.

Transabdominal Ultrasonography

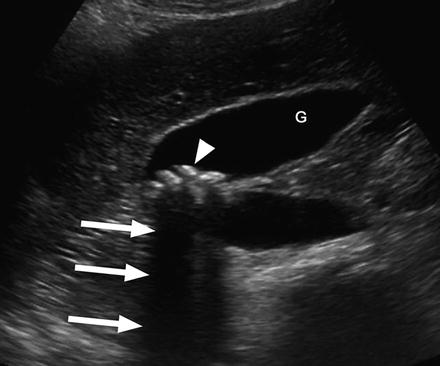

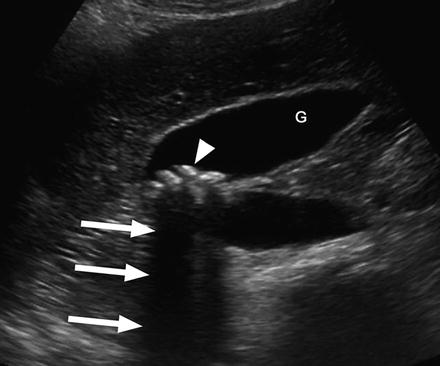

Ultrasonography is now considered the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of gallbladder or biliary tract pathology due to both its excellent sensitivity and specificity. The noninvasiveness, lack of radiation, relatively low cost, and ease of use add to its appeal. On transabdominal ultrasonography, gallstones appear as hyperechoic foci in the gallbladder lumen. Each stone carries an accompanying posterior acoustic shadow and lies in the dependent position due to gravity (Fig. 6.1). These characteristics help to differentiate gallstones from gallbladder polyps, which are also hyperechoic but are not in dependent positioning and do not contain a shadow. Limitations of ultrasonography include user technical proficiency, obese body habitus, and the presence of ascites.

Fig. 6.1

Typical sonographic appearance of gallstones as hyperechoic foci (arrowhead) in dependent positioning within the gallbladder lumen (G), and associated acoustic shadowing (arrows)

While patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis are not routinely screened, some populations warrant screening ultrasonography. These groups include New World Indians, such as Pima Indians, as well as in patients undergoing bariatric surgery, and in particular gastric bypass. However, numerous studies have shown minimal benefit for prophylactic cholecystectomy in bariatric surgery patients, and therefore some do not advocate routine imaging for these patients as is done for their nonobese counterparts [26–28].

Cholescintigraphy

Cholescintigraphy uses radiotracer material (hepatic 2,6-dimethyl-iminodiacetic acid—HIDA) in order to evaluate the liver, gallbladder, and biliary tree. With an HIDA scan, the tracer is taken up by the liver and excreted into the bile ducts. The primary use of this test is for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, signified by the absence of gallbladder visualization representing cystic duct obstruction from a gallstone. HIDA scanning is generally performed when ultrasound findings for acute cholecystitis are equivocal and has no role in determining the mere absence or presence of gallstones.

Computed Tomography

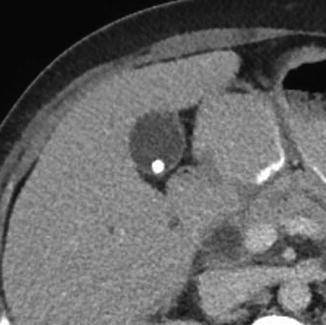

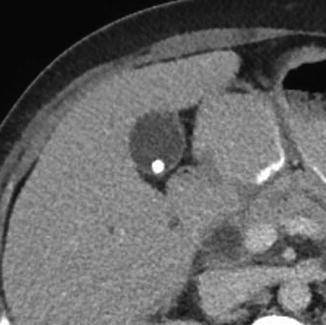

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is increasingly being performed for the evaluation of abdominal pain, especially in the Emergency Center setting. With this widespread use comes an increased incidence of cholelithiasis. Many of these patients present with a chief complaint that is non-biliary in origin and are found to have gallstones incidentally. For the assessment of cholelithiasis, CT scanning is less sensitive than ultrasonography, although radiopaque gallstones can be visualized if calcified (Fig. 6.2). The primary use for CT scanning as it relates to biliary pathology is to evaluate gallstone-related complications, including acute cholecystitis with abscess and pancreatitis.

Fig. 6.2

CT scan finding of cholelithiasis, with a solitary, calcified gallstone

Management

Surgical Therapy

The status of patient symptoms remains the most important factor in determining the appropriate management for cholelithiasis. Due to the increased risk for recurrent biliary colic or complicated gallstone disease, cholecystectomy is indicated in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis. Additionally, cholecystectomy is indicated after an episode of complicated biliary disease (acute cholecystitis or gallstone pancreatitis) because there may be a 30 % chance of having a recurrence of complicated disease within 3 months [29].

Conversely, the low rates of symptoms or complications in those with asymptomatic cholelithiasis are outweighed by the risks of surgery and added costs. As such, current practice guidelines indicate that cholecystectomy is not indicated for routine patients with asymptomatic cholelithiasis [30–32]. These guidelines are based on the natural history of silent gallstones, although no randomized trial comparing cholecystectomy vs. nonoperative management for asymptomatic cholelithiasis has been performed [33]. Only in very special circumstances are the risks associated with surgery in asymptomatic patients outweighed by the risks of gallstone complications or gallbladder cancer, as described below.

Certain patients carry a higher risk of developing gallbladder cancer. The classic teaching has been that patients with a calcified gallbladder, known as porcelain gallbladder, required cholecystectomy for fear that the vast majority of these would become malignant. We now know that the rates of cancer development among patients with porcelain gallbladder are much lower, in the realm of 2–3 % [34, 35]. Nonetheless, prophylactic cholecystectomy is still recommended in such patients. Anomalous pancreatic duct drainage is another risk factor for the development of gallbladder cancer. Generally, patients will have pancreatic duct drainage into the common bile duct proximal to the normal peri-ampullary position. In patients with this anomalous drainage but without choledochal cysts, gallbladder cancer was the most common malignancy seen and is the main indication for prophylactic cholecystectomy [36]. Larger gallbladder adenomas, 1 cm or larger, are associated with a significantly increased risk for gallbladder cancer, and as such, these patients should undergo cholecystectomy [37, 38]. In addition, patients who have both gallbladder polyps and gallstones should undergo cholecystectomy regardless of polyp size, since cholelithiasis is a risk factor for gallbladder cancer in those with gallbladder polyps [39].

Some have advocated for prophylactic cholecystectomy in certain patient subsets due to the high incidence of cholelithiasis and associated gallbladder cancer. The most well-known example is the New World Indians, such as Pima Indians, who carry a very high likelihood of gallstone disease, arguing for prophylactic cholecystectomy even in asymptomatic individuals [40]. Diabetes, once considered an indication for prophylactic cholecystectomy due to its increased risk for gangrenous cholecystitis, is no longer considered to be an indication. It is now known that the rates of conversion from initially asymptomatic to symptomatic or complicated gallstone disease among diabetic patients are similar to their nondiabetic counterparts [41].

As mentioned above, hemolytic disorders are common etiologies for pigmented stones. Specifically, those with sickle cell anemia and hereditary spherocytosis are at greater risk [42–44]. Almost half of sickle cell patients have gallstones by the third decade of life and gallstone-related complications can induce a sickle cell crisis. Most clinicians therefore recommend that these patients undergo prophylactic cholecystectomy, either alone or at the time of another abdominal procedure. A randomized study revealed that the laparoscopic approach to cholecystectomy resulted in shorter hospitalization and those patients receiving preoperative blood transfusion experienced less sickle cell events postoperatively [45].

In candidates for organ transplantation and those patients that are immunosuppressed, cholecystectomy is often recommended [21, 46]. The significant morbidity and mortality associated with acute cholecystitis and other gallstone-related complications in the setting of immunosuppression justifies prophylactic surgery in this patient cohort.

There is little debate that rapid weight loss following bariatric surgery results in a significantly increased incidence of cholelithiasis [47]. The argument for prophylactic cholecystectomy in patients undergoing bariatric surgery is that there is minimal associated increased risk or additional intraoperative time. Others advocate that the lack of added benefit precludes this practice and that such patients should therefore be treated in the same manner as nonobese, asymptomatic patients. One retrospective study with a median follow-up of 4 years found that post-bariatric patients underwent cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis at a rate of 7.8 % and was highest among those undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) as compared to adjustable gastric banding (AGB) or sleeve gastrectomy (SG) [48]. The strongest predictor for need for subsequent cholecystectomy was the amount of excess weight loss with the first 3 postoperative months. Given these findings, the authors of this study concluded that prophylactic cholecystectomy was not indicated at the time of primary bariatric operation. This topic remains without consensus opinion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree