CHAPTER 4 Management of Acute Low Back Pain

Many health care providers are routinely consulted for help with low back pain (LBP). LBP ranks as one of the top five reasons for seeking care and accounts for 5% of all visits to primary care providers (PCPs), doctors of chiropractic (DCs), and physical therapists (PTs).1–5 Together, these health care providers are responsible for a large proportion of patient visits for LBP in primary care settings.2,5,6 A sizeable number of those with LBP will also seek care in secondary care settings from both nonsurgical specialists such as neurologists, physiatrists, and rheumatologists, and surgical specialists such as orthopedic and neurologic spine surgeons.7 Patients with LBP also seek care from allied health providers, including acupuncturists, naturopaths, and psychologists, among many others.8

Differences in the training, education, scope of practice, and clinical experience among these various types of providers has led to noted variations in practice patterns for the management of LBP.9,10 Some of this variation is also attributable to the heterogeneous nature of patients with LBP, who may present with a variety of symptoms, including pain in the lumbosacral region, pain radiating into the lower extremity, muscle spasm, and limited range of motion, as well as numbness, tingling, or weakness in the thigh, leg, ankle, or foot. Only in very rare instances are such symptoms related to potentially serious spinal pathology or other specific causes of LBP that may benefit from medical or surgical interventions targeting specific anatomic structures.

Nevertheless, the current management of acute LBP is far from optimal. Although several clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have been conducted on this topic in the past two decades, compliance with their recommendations by PCPs, DCs, PTs, and other clinicians involved in managing LBP is often reported as low.11–26 Attempts to increase compliance with recommendations from CPGs among clinicians have reported mixed results.15,27–30

Barriers noted to the broader adoption of recommendations from CPGs by clinicians include a lack of understanding about how they are conducted, insufficient clarity to apply recommendations to specific patients, perceived inconsistencies among different CPGs, or disagreement by clinicians with specific recommendations from CPGs.31 Methods for CPGs are not yet standardized and can differ considerably, which may impact the validity of their recommendations.32,33 Previous reviews of CPGs related to LBP have reported that although many of their recommendations were similar, discrepancies were noted regarding the use of medication, spinal manipulation therapy (SMT), exercise, and patient education.9,34 Flaws were also noted in their methodologic quality, and suggestions were made for improving future CPGs related to LBP to increase their adoption by clinicians.34,35

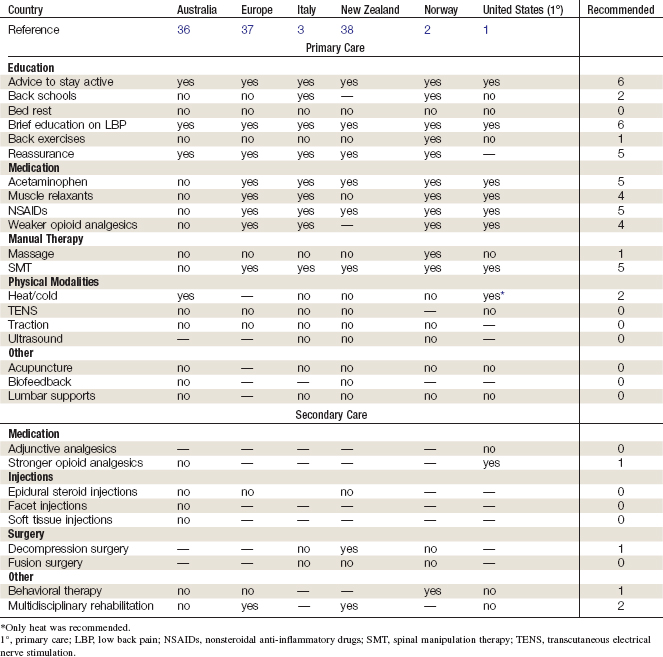

To foster an enhanced understanding of recommendations from evidence-based CPGs related to the management of LBP and evaluate any inconsistencies that may be present in these documents, a review and synthesis of recent CPGs was conducted.36 Only CPGs sponsored by national organizations related to both the assessment and management of LBP and which had been published in English in the past 10 years were included. Although 10 such CPGs were identified for this synthesis of recommendations, only 6 pertained to the management of acute LBP.1-3,37-39 Recommendations from CPGs about the use of specific interventions were dichotomized to “recommended” if there was strong, moderate, or limited evidence of efficacy (or similar wording), or “not recommended” if there was insufficient or conflicting evidence, or evidence against a particular intervention (or similar wording). When CPGs contained multiple recommendations about an intervention, the one contained in its summary was selected.

In addition, conclusions from recent high-quality systematic reviews (SRs) from the Cochrane Collaboration and those conducted by the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Pain Society (APS) in conjunction with their CPGs, were also summarized where appropriate. Interventions are presented according to their most likely setting, that is, primary care or secondary care. A distinction was often made in CPGs with respect to weaker opioid analgesics (e.g., codeine, tramadol) and stronger opioid analgesics (e.g., oxycodone, morphine); the former are grouped with primary care interventions, while the latter are discussed in secondary care interventions. Recommendations from the CPGs reviewed related to specific interventions encountered in primary care and secondary care for the management of acute LBP are summarized in Table 4-1.

TABLE 4-1 Recommendations from Clinical Practice Guidelines About Management of Patients with Acute Low Back Pain

Primary Care Interventions

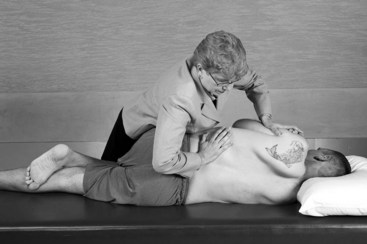

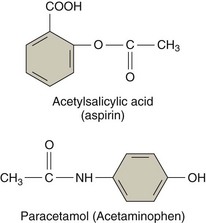

The most commonly discussed primary care interventions for the management of acute LBP were centered on patient education, medications, manual therapy, physical modalities, and other interventions. Each is briefly discussed here. Some of the primary care interventions that were generally recommended by CPGs for acute LBP are also illustrated in Figures 4-1 through 4-4.

Figure 4-2 Generally recommended for acute low back pain: advice to remain active.

(From Muscolino JE: Kinesiology: the skeletal system and muscle function, ed. 2. St. Louis, 2011, Elsevier.)

Figure 4-3 Generally recommended for acute low back pain: simple analgesics.

(Adapted from Wecker L: Brody’s human pharmacology, ed. 5. Philadelphia, 2010, Elsevier.)

Patient Education

Brief Education

An SR conducted in 2008 by the Cochrane Collaboration on patient education for nonspecific acute LBP identified 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs).40 This review found that a 2.5-hour individual patient education session was more effective than no intervention and was equally effective as noneducational interventions (i.e., SMT, physical therapy). However, shorter education sessions, such as written educational materials, were not more effective than no intervention.

Back Schools

An SR conducted in 1999 and updated in 2003 by the Cochrane Collaboration on back schools for nonspecific acute LBP included four RCTs.41–43 The review reported conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of back schools for acute LBP. An SR conducted in 2006 by the APS and ACP on back schools for acute LBP identified three SRs on this topic, including the Cochrane SR described previously.44

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree