CHAPTER 9 Lumbar Strengthening Exercise

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

Exercise, loosely translated from Greek, means “freed movement” and describes a wide range of physical activities. Therapeutic exercise indicates that the purpose of the exercise is for the treatment of a specific medical condition rather than recreation. The main types of therapeutic exercise relevant to chronic low back pain (CLBP) include (1) general physical activity as usual (e.g., advice to remain active), (2) aerobic (e.g., brisk walking, cycling), (3) aquatic (e.g., swimming, exercise classes in a pool), (4) directional preference (e.g., McKenzie), (5) flexibility (e.g., stretching, yoga, Pilates), (6) proprioceptive/coordination (e.g., wobble board, stability ball), (7) stabilization (e.g., targeting abdominal and trunk muscles), and (8) strengthening (e.g., lifting weights).1 This chapter focuses exclusively on strengthening exercises of the lumbar extensors for CLBP.

Lumbar Extensors

The term lumbar extensor is used colloquially to refer to the erector spinae muscle group, which is comprised of the iliocostalis lumborum, longissimus thoracis, and spinalis thoracis. These three long, narrow muscles are positioned lateral to the multifidus, have a common origin on the upper iliac crest and lumbar aponeurosis, and each inserts on several ribs superiorly.2 The erector spinae allow for vertebral rotation in the sagittal plane (e.g., lumbar extension) and posterior vertebral translation when muscles contract bilaterally.3 The multifidus muscle is also involved with lumbar extension movements and is therefore a target of lumbar strengthening exercises. The fascicular arrangement of the multifidus suggests that this muscle assists the erector spinae group and acts on vertebral rotation in the sagittal plane without posterior translation. Both the multifidus and erector spinae are also capable of vertebral rotation in the coronal plane (e.g., lumbar lateral flexion) and transverse plane (e.g., axial rotation) with unilateral contraction.4

Strengthening Exercises

Strengthening exercises are also known as progressive resistance exercise (PRE), which is based on the principles of overload, specificity, reversibility, frequency, intensity, repetitions, volume, duration, and mode. Each of these concepts is briefly discussed here as it relates to lumbar extensor strengthening exercises.5,6

Overload

For PRE to result in continued increases in muscular strength and endurance, training must progressively overload the targeted musculature, that is, make muscles function beyond their current capacity by increasing the intensity and volume of exercises.6 Overloading the intensity of exercise tends to produce gains in muscular strength, whereas overloading the volume of exercise tends to improve muscular endurance. Although important to achieve long-term goals, overload in intensity and volume should be gradual to avoid reinjury.7

Specificity

Specificity implies that the target muscle must be isolated during the prescribed exercises to achieve sufficient muscular activation.6 Trunk extension is a compound movement of the hip, pelvis, and lumbar spine through the action of the lumbar extensors, gluteals, and hamstrings.8 The relative contribution of individual muscle groups is unknown, but it is assumed that the larger gluteal and hamstring muscles generate the majority of the force.9 Therefore it has been suggested that to enhance specificity for the lumbar extensors, torque production from the gluteals and hamstrings should be minimized.8 This can be achieved through various types of equipment and techniques. The lumbar dynamometer, for example, incorporates restraint mechanisms to limit pelvic and hip rotation and maximize lumbar extension in the seated position.10 Similarly, prone back extensions on Roman chairs or benches improve specificity and isolation of the lumbar extensors by aligning the pelvis on the device, internally rotating the hips, and accentuating lumbar lordosis.11

Reversibility

With all PRE training programs, much of the gains in muscular strength and endurance will be lost unless exercise is continued.6 To prevent this reversibility, it is recommended that therapeutic exercises be carried out long term. Once substantial improvement has been achieved, it may be possible to maintain physiologic gains with a reduced training frequency that may be as low as once per month.12

Frequency

The optimal frequency for PRE varies based on initial physical condition, duration of injury, and therapeutic goals. Generally, a frequency of one to three sessions per week of PRE is recommended.13 Patients who are most deconditioned may initially achieve gains with only one session per week, which must be gradually increased to exceed that improvement.14,15 Studies have reported improvement in lumbar extensor strength in patients with CLBP who trained once per week; no differences were noted between two and three sessions per week.16,17 Training frequency needs to also consider intensity and volume, because particularly challenging PRE sessions may require additional recovery time.6 It is often suggested that patients allow for at least 48 hours between sessions.

Intensity

The intensity of PRE is related to both the amount of resistance used (e.g., weight) and the number of repetitions. To increase muscle strength, high-intensity PRE consisting of higher resistance and lower repetitions is generally prescribed, whereas low-intensity PRE with lower resistance and higher repetition is used to improve muscular endurance.6 Depending on the therapeutic goals (e.g., strength vs. endurance), 6 to 25 repetitions at intensities of 30% to 85% of the theoretical maximum intensity can be used for PRE. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of PRE for CLBP, there were no differences in clinical outcomes between high- and low-intensity lumbar extensor strength training.18

Repetitions

In PRE, the number of repetitions is corollary to the amount of resistance: as resistance increases, repetitions decrease. Regardless of the number, each repetition of a particular exercise should be performed in a slow, controlled fashion. It has been suggested that, as a general rule, it should take two seconds for the concentric/shortening phase and four seconds for the eccentric/lengthening phase of a PRE.19

Volume

The volume of PRE refers to the number of sets performed at one time and is one of the elements that can be varied to maintain gains in strength and endurance once a certain level of resistance and repetitions can be comfortably achieved. Although the optimal volume of PRE is unknown, one to three sets of each exercise is typically recommended for each session.13 For asymptomatic individuals, lumbar extensor strength gains achieved with one set of exercises were equal to those achieved with three sets when using a dynamometer.19 However, in patients with CLBP, an RCT reported that clinical outcomes were maximized with an increased volume of prone back extension exercises on benches.20

Duration

In the context of PRE, duration refers to the total length of the exercise program and not the length of individual sessions. Clinical improvement can be seen after only a few weeks of a resistance training program due to changes in specific physical function, whereas long-term improvements are attributable to physiologic changes as a result of PRE.6 A minimum of 10 to 12 weeks of PRE is generally required to achieve measurable physiologic changes (e.g., hypertrophy) in skeletal muscles.6 However, compliance with any therapeutic exercise program tends to decrease over time and it can be challenging to maintain patient participation for that period once functional improvements are achieved and symptoms diminish.

Mode

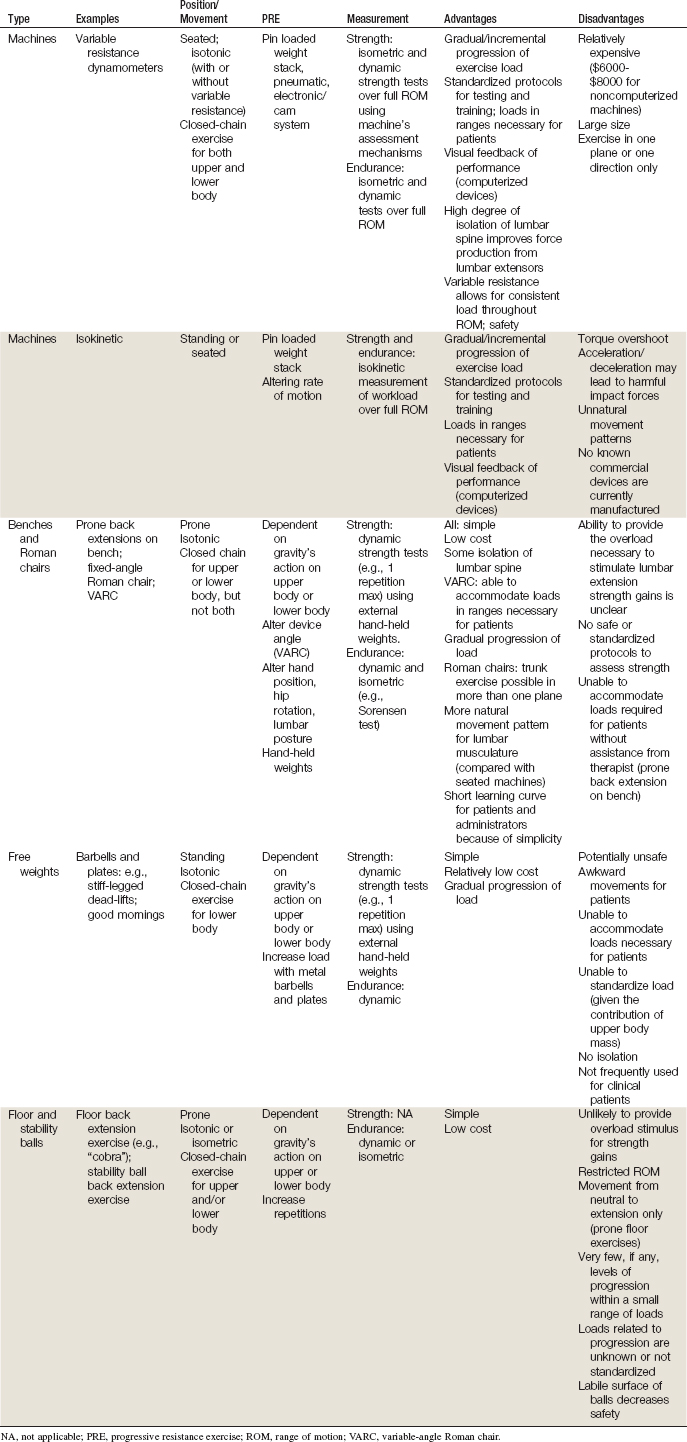

Mode refers to the specific type of exercises and equipment used during PRE.6 This can be defined according to muscular contractions, which are either isometric or dynamic. Isometric exercise implies that the targeted muscle contracts without changing its length, whereas dynamic exercise implies that the targeted muscle shortens (concentric phase) or lengthens (eccentric phase) while contracting, which also results in associated joint movement. The three categories of dynamic exercise are isotonic, variable resistance, and isokinetic.6 Isotonic dynamic exercise involves muscular contraction against a fixed resistance providing constant tension (e.g., dumbbells). Variable resistance dynamic exercise involves a muscular contraction against variable resistance that attempts to mimic the strength curve of the targeted muscle (e.g., Nautilus). Isokinetic dynamic exercise involves muscular contraction at fixed speed (e.g., treadmill). The five main modes of lumbar extensor strengthening exercise protocols use (1) machines (Figure 9-1), (2) benches (Figure 9-2), (3) Roman chairs (Figure 9-3), (4) free weights (Figure 9-4), and (5) stability balls (Figure 9-5). The characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of each are highlighted in Table 9-1.

History and Frequency of Use

Physical exercise has been used throughout human history. Hippocrates noted that lack of exercise led to atrophy, liability for disease, and quicker aging.7 In 1865, Gustav Zander developed a technique named medical mechanical therapy using exercise equipment, including a device to strengthen the back extensors.21 Although Zander described progressive exercise using equipment in the late 1800s, the idea did not receive much attention in the medical community for treating disease.7 The first known treatment program for musculoskeletal care that can likely be characterized as therapeutic exercise was by Thomas De Lorme in 1945 for rehabilitation of injured or postsurgical joints.22 The PREs were founded on the principles of weightlifters and bodybuilders using free weights (barbells and dumbbells) in a progressively demanding approach by increasing the amount of weight and number of repetitions. Today’s athletic training programs continue to use these basic PRE principles. Exercise equipment specifically designed to treat CLBP by strengthening the lumbar extensors through PREs appeared in the late 1980s. Soon after this, protocols were published for isometric testing and dynamic variable resistance training on dynamometers that isolated the lumbar spine.6,8 The availability of these measurement-based machines made it possible to more clearly define the dose of exercise during the treatment of CLBP. Although dynamometers and isokinetic machines effectively administer PREs to strengthen the lumbar extensors, the use of these machines for CLBP has been questioned because of their relatively high cost and inconvenience.23,24 As a result, less costly protocols were developed including fixed-angle Roman chairs and benches, variable-angle Roman chairs (VARC), floor exercises, and stability balls. However, it is still unclear whether these options provide the overload stimulus necessary to elicit clinically meaningful gains in lumbar extensor strength.25,26

Procedure

Lumbar Extension Dynamometer

The lumbar dynamometer allows for dynamic exercise through a 72-degree arc in the sagittal plane, with an adjustable weight stack to provide resistance from 9 kg to 364 kg in 0.5-kg increments.8 Variable resistance is accomplished through a cam with a flexion-extension ratio of 1.4:1. After securing the pelvic restraint mechanisms, the patient begins this exercise in the most flexed position that is pain free, and is instructed to extend their back into a position near terminal extension in a smooth, controlled manner, taking 2 seconds for the concentric phase (lifting the weight) and 4 seconds for the eccentric phase (lowering the weight). The supervising therapist typically provides encouragement to the patient to perform as many repetitions as possible. The machine itself also provides visual feedback on performance via a monitor that displays exercise load and position. When the patient is able to complete 20 or more repetitions with a particular resistance, the resistance is increased in 5% increments at the next training session.1

Variable-Angle Roman Chair

The VARC is similar to fixed-angle Roman chairs, except that the angle can be adjusted from 75 degrees (nearly vertical) to 0 degrees (parallel to the ground) in 15-degree increments.26 Patients typically begin the training program at a low resistance level with an angle setting of 60 degrees with their hands positioned on their sternum. After achieving the correct positioning on the device, the patients start each repetition of dynamic exercise in the extended position and lower their trunk in a smooth, controlled fashion, completing the eccentric phase in 4 seconds. Next, patients raise their torso during the concentric phase in 2 seconds and are verbally encouraged by the supervising therapist to perform as many repetitions as possible. When patients complete 20 to 25 or more repetitions at one angle, resistance is increased. Gradual PRE is achieved by altering the angle setting and the subject’s hand position.25 Internally rotating the hips and accentuating lumbar intersegmental extension during lumbar extension further optimizes targeted muscle activity.25

Theory

Mechanism of Action

In general, exercises are used to strengthen muscles, increase soft tissue stability, restore range of movement, improve cardiovascular conditioning, increase proprioception, and reduce fear of movement. The mechanism of action of lumbar extensor strengthening exercise is likely related to the physiologic effects of conditioning the lumbar muscles through PRE, enhancing the metabolic exchange of the lumbar discs through repetitive movement, as well as the psychological mechanisms involving kinesiophobia and locus of control; each is briefly described here.1,16,18,27

Conditioning Lumbar Musculature

The lumbar extensor muscles have long been considered the “weak link” in lower trunk function.9 For patients with CLBP, the lumbar extensors have been described as weak, atrophied, and highly fatigable, displaying abnormal activation patterns and excessive fatty infiltration.15,28–30 It is therefore reasonable to focus on conditioning these muscles through PREs to improve their physiologic and structural integrity. Reversal of muscular dysfunction and structural abnormalities has been documented in patients with CLBP following lumbar extensor strengthening exercises.16,31 Both isolation and progressive overload of the lumbar extensors are necessary to achieve these benefits.

Lumbar extensor PREs on machines, benches, or Roman chairs likely provide sufficient isolation and overload to improve lumbar muscular strength and endurance.9,20,26 Whether or not appropriate isolation and overload actually occur from low load floor exercise (e.g., lumbar stabilization) or stability ball exercise is currently unknown. In a recent study by Sung,32 no change in the fatigue status of the lumbar multifidus was noted after a 4-week supervised stabilization exercise program. In another study, the effect of three different exercise-training modalities on the cross-sectional area of the lumbar extensor muscles of patients with CLBP was assessed.33 Stabilization exercise alone was not sufficient to change lumbar muscle cross-sectional area but when combined with dynamic and isometric intensive resistance training, an increase in cross-sectional area of the musculature was noted.

Disc Metabolism

Disc metabolism could potentially be enhanced through repetitive exercise involving the spine’s full active range of motion, as performed with lumbar extensor strengthening exercises. Given that the absence of physical activity is known to reduce a healthy metabolism, it appears reasonable to believe that introducing exercise such as lumbar extensor strengthening may reverse such findings.1 The association between biochemical abnormalities in the lumbar discs and CLBP has previously been documented.34 Enhanced disc metabolism could improve repair and enhance reuptake of inflammatory and nociceptive mediators that may have migrated to an area of injury.

Indication

Lumbar extensor strengthening exercises are typically indicated for nonspecific CLBP of mechanical origin.1 Although these exercises are likely most appropriate for those with CLBP who have suspected or demonstrated deficiencies in muscle strength, endurance, or coordination, they have been shown to be beneficial for those with wide ranges of muscular capacities at treatment onset.35,36 Based on anecdotal experience, the ideal CLBP patient for this intervention is one who is in good general health, both physically and psychologically, and is willing to take responsibility for his or her own self-care by committing to an active exercise program. As is typical of any strenuous exercise activity, lumbar extensor strengthening exercise may be associated with some short-term discomfort. Thus, the recognition of long-term benefit by the patient and subsequent compliance to the program, despite the possibility of short-term discomfort, optimizes their chance for positive outcomes.

Assessment

Before initiating lumbar extensor strengthening exercises, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Additional diagnostic imaging or specific diagnostic testing is generally not required before initiating these interventions for CLBP. Nevertheless, several diagnostic tests are used clinically to apply the proper and safe dose of exercise, monitor progress throughout treatment, and document that the target muscles are being appropriately activated. These include standardized tests for isometric lumbar extension strength and endurance (e.g., Biering-Sorenson test) and assessment of lumbar muscle activity through real-time ultrasound and surface electromyography.16,32,37,38 More technologically advanced options to assess lumbar muscle cross-sectional area, fatty infiltration, and activation patterns include magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scanning.15,39,40 It should be noted that these tests are typically reserved for research settings and are not typically required for clinical practice.