CHAPTER 119

Lumbar Strain, Acute

(“Mechanical” Low Back Pain, Sacroiliac Dysfunction)

Presentation

Suddenly or gradually, after lifting, sneezing, bending, or other movement, the patient develops a steady pain in one or both sides of the lower back. At times, this pain can be severe and incapacitating. It is usually better when lying down, worse with movement, and will perhaps radiate around the abdomen or down the thigh but no farther. There is insufficient trauma to suspect bony injury (e.g., a fall or direct blow) and no evidence of systemic disease that would make bony disease likely (e.g., osteoporosis, metastatic carcinoma, multiple myeloma). On physical examination, there may be spasm in the paraspinous muscles (i.e., contraction that does not relax, even when the patient is supine or when the opposing muscle groups contract, as with walking in place), but there is no point tenderness over the spinous processes of lumbar vertebrae and no nerve root signs, such as pain or paresthesia in dermatomes below the knee (especially with straight-leg raising), no foot weakness, and no loss of the ankle jerk. There may be point tenderness to firm palpation or percussion over the sacroiliac joint (SIJ), especially if the patient complains of pain toward that side of his lower back.

What To Do:

Perform a complete history and physical examination of the abdomen, back, and legs, looking for alternative causes for the back pain. Pay special attention to red flags, such as a history of significant trauma, cancer, weight loss, fever, night sweats, injection drug use, compromised immunity, recumbent night pain, severe and unremitting pain, urinary retention or incontinence, saddle anesthesia, and severe or rapidly progressing neurologic deficit. Red flags on physical examination include elderly patients, fever, spinous point tenderness to percussion, abdominal tenderness or mass, and lower extremity motor weakness.

Perform a complete history and physical examination of the abdomen, back, and legs, looking for alternative causes for the back pain. Pay special attention to red flags, such as a history of significant trauma, cancer, weight loss, fever, night sweats, injection drug use, compromised immunity, recumbent night pain, severe and unremitting pain, urinary retention or incontinence, saddle anesthesia, and severe or rapidly progressing neurologic deficit. Red flags on physical examination include elderly patients, fever, spinous point tenderness to percussion, abdominal tenderness or mass, and lower extremity motor weakness.

Radiographs are generally not required, but consider obtaining plain radiographs of the lumbosacral spine on patients who have suffered injury that is sufficient to cause bony injury. Mild trauma in patients who are older than 50 years, patients younger than 20 years of age with nontraumatic pain, or patients older than 50 years of age who have had pain for more than a month warrant radiographs. Radiographs should also be ordered for patients who are on long-term corticosteroid medication, patients with a history of osteoporosis or cancer, and patients who are older than 70 years of age. A negative radiograph does not rule out disease.

Radiographs are generally not required, but consider obtaining plain radiographs of the lumbosacral spine on patients who have suffered injury that is sufficient to cause bony injury. Mild trauma in patients who are older than 50 years, patients younger than 20 years of age with nontraumatic pain, or patients older than 50 years of age who have had pain for more than a month warrant radiographs. Radiographs should also be ordered for patients who are on long-term corticosteroid medication, patients with a history of osteoporosis or cancer, and patients who are older than 70 years of age. A negative radiograph does not rule out disease.

Laboratory investigation is generally not indicated, but order a complete blood count (CBC) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) on patients with a history of immune deficiency, cancer or IV drug abuse, or signs or symptoms of underlying systemic disease (e.g., unexplained weight loss, fatigue, night sweats, fever, lymphadenopathy, and back pain at night or that is unrelieved by bed rest) or children who are limping, refuse to walk, or bend forward. Bone scans, CT scans, or MRI may be better than plain radiographs in these patients. Consider diagnoses such as multiple myeloma, vertebral osteomyelitis, spinal tumor, diskitis, or spinal subdural abscess. Bedside ultrasonography, if the physician is trained in this technique, should be obtained to rule out an abdominal aortic aneurysm. If the physician is untrained or there is evidence of aneurysm on ultrasonography, an abdominal CT should be obtained immediately.

Laboratory investigation is generally not indicated, but order a complete blood count (CBC) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) on patients with a history of immune deficiency, cancer or IV drug abuse, or signs or symptoms of underlying systemic disease (e.g., unexplained weight loss, fatigue, night sweats, fever, lymphadenopathy, and back pain at night or that is unrelieved by bed rest) or children who are limping, refuse to walk, or bend forward. Bone scans, CT scans, or MRI may be better than plain radiographs in these patients. Consider diagnoses such as multiple myeloma, vertebral osteomyelitis, spinal tumor, diskitis, or spinal subdural abscess. Bedside ultrasonography, if the physician is trained in this technique, should be obtained to rule out an abdominal aortic aneurysm. If the physician is untrained or there is evidence of aneurysm on ultrasonography, an abdominal CT should be obtained immediately.

Consider disk herniation when leg pain overshadows the back pain. Back pain may subside as leg pain worsens. This pain tends to worsen with coughing, Valsalva maneuver, trunk flexion, and prolonged sitting or standing. Look for weakness of ankle or great-toe dorsiflexion (drooping of the big toe and inability to heel walk). Also look for decreased sensation to pinprick over the medial dorsal foot when there is compression of the fifth lumbar nerve root. Look for weak plantar flexion (inability to toe walk), diminished ankle reflex, and paresthesias or decreased sensation to pinprick of the lateral or plantar aspect of the foot when there is first sacral root compression (L5 and S1 radiculopathy account for about 90% to 95% of all lumbar radiculopathies). Raise each leg 30 to 60 degrees of elevation from the horizontal, and consider the test positive for nerve root compression if it produces pain down the leg below the knee along a nerve root distribution, rather than pain in the back. This leg pain is increased by dorsiflexion of the foot and relieved by plantar flexion. Pain generated at less than 30 degrees and greater than 70 degrees is nonspecific. Ipsilateral straight-leg raising is a moderately sensitive but not a specific test. A herniated intervertebral disk is more strongly indicated when contralateral radicular pain is reproduced in one leg by raising the opposite leg. If nerve root compression is suspected, prescribe short-term bed rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Arrange for general medical, orthopedic, or neurosurgical referral. Although controversial, some consultants recommend short-term corticosteroid treatment, such as prednisone, 50 mg qd × 5 days. It should be noted that the 2007 joint guidelines of the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society recommend against using systemic steroids. This is because of a lack of proven benefit. The patient should try at least 4 to 6 weeks of conservative treatment before submitting to an operation on the herniated disk. Surgical treatment should be routinely avoided for patients with disk herniation and radiating pain in the absence of neurologic findings. Eighty percent of patients with sciatica recover with or without surgery. The presence of significant weakness in a myotome is perhaps the most important factor in the decision to perform a relatively early surgical procedure. If the weakness is profound or rapidly progressive, delaying surgery increases the risk for permanent deficit. The rare cauda equina syndrome is the only complication of lumbar disk herniation that calls for emergent surgical referral. It occurs when a massive extrusion of disk nucleus compresses the caudal sac containing lumbar and sacral nerve roots. Bilateral radicular leg pain or weakness, bladder or bowel dysfunction, perineal or perianal anesthesia, decreased rectal sphincter tone in 60% to 80% of cases, and urinary retention in 90% of cases are common findings. An emergent MRI is the study of choice for confirming this diagnosis.

Consider disk herniation when leg pain overshadows the back pain. Back pain may subside as leg pain worsens. This pain tends to worsen with coughing, Valsalva maneuver, trunk flexion, and prolonged sitting or standing. Look for weakness of ankle or great-toe dorsiflexion (drooping of the big toe and inability to heel walk). Also look for decreased sensation to pinprick over the medial dorsal foot when there is compression of the fifth lumbar nerve root. Look for weak plantar flexion (inability to toe walk), diminished ankle reflex, and paresthesias or decreased sensation to pinprick of the lateral or plantar aspect of the foot when there is first sacral root compression (L5 and S1 radiculopathy account for about 90% to 95% of all lumbar radiculopathies). Raise each leg 30 to 60 degrees of elevation from the horizontal, and consider the test positive for nerve root compression if it produces pain down the leg below the knee along a nerve root distribution, rather than pain in the back. This leg pain is increased by dorsiflexion of the foot and relieved by plantar flexion. Pain generated at less than 30 degrees and greater than 70 degrees is nonspecific. Ipsilateral straight-leg raising is a moderately sensitive but not a specific test. A herniated intervertebral disk is more strongly indicated when contralateral radicular pain is reproduced in one leg by raising the opposite leg. If nerve root compression is suspected, prescribe short-term bed rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Arrange for general medical, orthopedic, or neurosurgical referral. Although controversial, some consultants recommend short-term corticosteroid treatment, such as prednisone, 50 mg qd × 5 days. It should be noted that the 2007 joint guidelines of the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society recommend against using systemic steroids. This is because of a lack of proven benefit. The patient should try at least 4 to 6 weeks of conservative treatment before submitting to an operation on the herniated disk. Surgical treatment should be routinely avoided for patients with disk herniation and radiating pain in the absence of neurologic findings. Eighty percent of patients with sciatica recover with or without surgery. The presence of significant weakness in a myotome is perhaps the most important factor in the decision to perform a relatively early surgical procedure. If the weakness is profound or rapidly progressive, delaying surgery increases the risk for permanent deficit. The rare cauda equina syndrome is the only complication of lumbar disk herniation that calls for emergent surgical referral. It occurs when a massive extrusion of disk nucleus compresses the caudal sac containing lumbar and sacral nerve roots. Bilateral radicular leg pain or weakness, bladder or bowel dysfunction, perineal or perianal anesthesia, decreased rectal sphincter tone in 60% to 80% of cases, and urinary retention in 90% of cases are common findings. An emergent MRI is the study of choice for confirming this diagnosis.

For patients who have nonspecific pain that can be treated in an outpatient setting, prescribe a short course of anti-inflammatory analgesics (ibuprofen, naproxen) for patients who do not have any contraindications for using them. Because gastric bleeding and renal insufficiency are common with long-term use of NSAIDs, consider substituting acetaminophen (Tylenol), 1000 mg q4-6h (maximum four doses daily), especially in the older patient. (Give half this dose if the patient takes greater than or equal to three alcoholic drinks per day.) Also consider a short-term opiate, such as hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lorcet) or oxycodone (Percocet), if necessary. A brief course of a muscle relaxant, such as metaxalone (Skelaxin), 800 mg tid to qid (less drowsiness), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), 10 mg bid to qid (not recommended for the elderly), or lorazepam (Ativan) 0.5 to 1.0 mg qid (more sedating and care should also be taken in the elderly), may be effective. The potential benefits must be weighed against the increased rates of dizziness and drowsiness that accompany the use of muscle relaxants.

For patients who have nonspecific pain that can be treated in an outpatient setting, prescribe a short course of anti-inflammatory analgesics (ibuprofen, naproxen) for patients who do not have any contraindications for using them. Because gastric bleeding and renal insufficiency are common with long-term use of NSAIDs, consider substituting acetaminophen (Tylenol), 1000 mg q4-6h (maximum four doses daily), especially in the older patient. (Give half this dose if the patient takes greater than or equal to three alcoholic drinks per day.) Also consider a short-term opiate, such as hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lorcet) or oxycodone (Percocet), if necessary. A brief course of a muscle relaxant, such as metaxalone (Skelaxin), 800 mg tid to qid (less drowsiness), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), 10 mg bid to qid (not recommended for the elderly), or lorazepam (Ativan) 0.5 to 1.0 mg qid (more sedating and care should also be taken in the elderly), may be effective. The potential benefits must be weighed against the increased rates of dizziness and drowsiness that accompany the use of muscle relaxants.

Recommend hot or cold packs (whichever the patient chooses) or alternate both hot and cold. Although not scientifically supported, these packs can often be comforting.

Recommend hot or cold packs (whichever the patient chooses) or alternate both hot and cold. Although not scientifically supported, these packs can often be comforting.

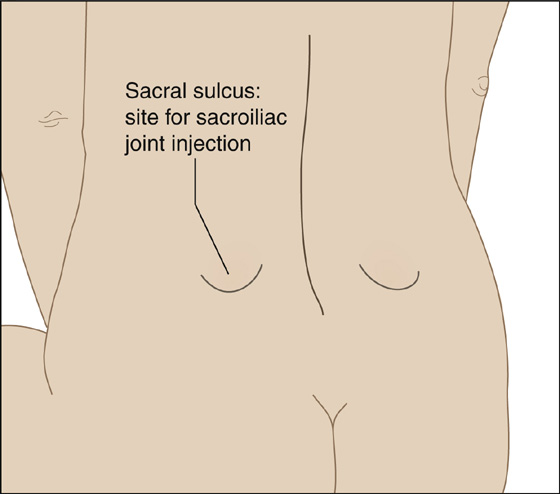

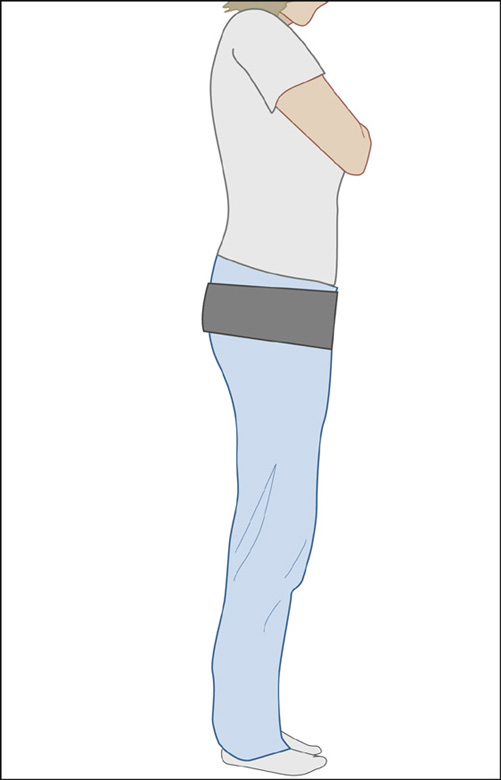

At times sacroiliac dysfunction can cause incapacitating spasms of pain that are precipitated by minor movements or attempts to sit up. The patient will usually be able to localize the pain to the right or left side of the sacrum. Firmly palpating the dimple (sacral sulcus) with your thumb and eliciting pain may be the most reliable indication of SIJ pain. When the pain is significant and there are no neurologic findings to suggest nerve root compression or any red flags of underlying systemic disease, it can be quite rewarding to provide an intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic mixed with a corticosteroid. Improvement of pain is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Draw up 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) mixed with 1 mL (40 mg) of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol) or 1 to 2 mL (6 to 12 mg) of betamethasone (Celestone Soluspan). Using a 1¼-inch, 22- to 27-gauge needle and sterile technique, inject deeply into the sacroiliac joint at the point of maximal tenderness or into the sacral sulcus immediately lateral to the sacrum (Figure 119-1). When the needle is in the joint, the needle should advance freely up to its hub without meeting resistance or bony obstruction. There should be a free flow of medication from the syringe without causing soft tissue swelling. If the needle meets any obstruction, reposition it with slight angulation of the needle tip out laterally until the needle advances easily. During the injection, fan upward into the superior fibrous tissue of the SIJ. The patient may feel a brief increase of pain, followed by dramatic relief in 5 to 20 minutes that is usually persistent. Pain is often relieved by 50% to 80%. Warn the patient that there may be a flare in pain when the anesthetic component wears off that could last for 24 to 48 hours. If the patient gets relief initially, any persistent symptoms should subside over the next 5 to 10 days. This should be performed in instances of acute pain, or an acute flare-up of chronic recurrent sacroiliac pain. Sacroiliac or SIJ belts can be used to provide compression, and, in some patients, stabilization and pain relief for SIJ dysfunction (samples can be found on the internet). The belt should be secured posteriorly across the sacral base and anteriorly, inferior to the anterior superior iliac spines (Figure 119-2). This belt may be most helpful during walking and standing activities, but for some patients with significant pain and weakness, wearing it during sedentary activities may also be helpful in reducing symptoms.

At times sacroiliac dysfunction can cause incapacitating spasms of pain that are precipitated by minor movements or attempts to sit up. The patient will usually be able to localize the pain to the right or left side of the sacrum. Firmly palpating the dimple (sacral sulcus) with your thumb and eliciting pain may be the most reliable indication of SIJ pain. When the pain is significant and there are no neurologic findings to suggest nerve root compression or any red flags of underlying systemic disease, it can be quite rewarding to provide an intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic mixed with a corticosteroid. Improvement of pain is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Draw up 10 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) mixed with 1 mL (40 mg) of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol) or 1 to 2 mL (6 to 12 mg) of betamethasone (Celestone Soluspan). Using a 1¼-inch, 22- to 27-gauge needle and sterile technique, inject deeply into the sacroiliac joint at the point of maximal tenderness or into the sacral sulcus immediately lateral to the sacrum (Figure 119-1). When the needle is in the joint, the needle should advance freely up to its hub without meeting resistance or bony obstruction. There should be a free flow of medication from the syringe without causing soft tissue swelling. If the needle meets any obstruction, reposition it with slight angulation of the needle tip out laterally until the needle advances easily. During the injection, fan upward into the superior fibrous tissue of the SIJ. The patient may feel a brief increase of pain, followed by dramatic relief in 5 to 20 minutes that is usually persistent. Pain is often relieved by 50% to 80%. Warn the patient that there may be a flare in pain when the anesthetic component wears off that could last for 24 to 48 hours. If the patient gets relief initially, any persistent symptoms should subside over the next 5 to 10 days. This should be performed in instances of acute pain, or an acute flare-up of chronic recurrent sacroiliac pain. Sacroiliac or SIJ belts can be used to provide compression, and, in some patients, stabilization and pain relief for SIJ dysfunction (samples can be found on the internet). The belt should be secured posteriorly across the sacral base and anteriorly, inferior to the anterior superior iliac spines (Figure 119-2). This belt may be most helpful during walking and standing activities, but for some patients with significant pain and weakness, wearing it during sedentary activities may also be helpful in reducing symptoms.

Figure 119-1 The dimple on either side of the sacrum (sacral sulcus) can serve as a landmark for injecting a painful sacroiliac joint.

Figure 119-2 Sacroiliac joint (SIJ) belt.

For point tenderness of the lumbosacral muscles, substantial pain relief may also be obtained by injecting 10 to 20 mL of 0.25% to 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) deeply into the points of maximal tenderness of the erector spinae and quadratus lumborum muscles, using a 1¼-inch, 25- to 27-gauge needle. Quickly puncture the skin, drive the needle into the muscle belly, and inject the anesthetic, slowly advancing and withdrawing the needle and fanning out the medication in all directions. Often one fan block can reduce symptoms by 95% after injection and yield a 75% permanent reduction of painful spasms. Following injection, teach stretching exercises.

For point tenderness of the lumbosacral muscles, substantial pain relief may also be obtained by injecting 10 to 20 mL of 0.25% to 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcaine) deeply into the points of maximal tenderness of the erector spinae and quadratus lumborum muscles, using a 1¼-inch, 25- to 27-gauge needle. Quickly puncture the skin, drive the needle into the muscle belly, and inject the anesthetic, slowly advancing and withdrawing the needle and fanning out the medication in all directions. Often one fan block can reduce symptoms by 95% after injection and yield a 75% permanent reduction of painful spasms. Following injection, teach stretching exercises.

For severe pain that cannot be relieved by injections of local anesthetic, it may be necessary to provide the patient with 1 to 2 days of bed rest, although most patients with acute low back pain recover more rapidly by continuing ordinary activities (within the limits permitted by their pain) than with bed rest or back-mobilizing exercises. Some patients with intractable excruciating pain (especially the elderly) require hospitalization.

For severe pain that cannot be relieved by injections of local anesthetic, it may be necessary to provide the patient with 1 to 2 days of bed rest, although most patients with acute low back pain recover more rapidly by continuing ordinary activities (within the limits permitted by their pain) than with bed rest or back-mobilizing exercises. Some patients with intractable excruciating pain (especially the elderly) require hospitalization.

Refer patients with uncomplicated back pain to their primary care provider for follow-up care in 3 to 7 days. Reassure patients that back pain is seldom disabling and that it usually resolves rapidly with their return to normal activity. Tell patients that the pain may be recurrent and that cigarette smoking, sedentary activity, and obesity are risk factors for back pain. Teach them to avoid twisting and bending when lifting, and show them how to lift with the back vertical, using thigh muscles and holding heavy objects close to the chest to avoid reinjury. Encourage them to return to work or resume normal activities as soon as possible, with neither bed rest nor exercise in the acute phase, and to participate in an aerobic exercise program when the pain has subsided. Heavy lifting, trunk twisting, and bodily vibration should be avoided in the acute phase.

Refer patients with uncomplicated back pain to their primary care provider for follow-up care in 3 to 7 days. Reassure patients that back pain is seldom disabling and that it usually resolves rapidly with their return to normal activity. Tell patients that the pain may be recurrent and that cigarette smoking, sedentary activity, and obesity are risk factors for back pain. Teach them to avoid twisting and bending when lifting, and show them how to lift with the back vertical, using thigh muscles and holding heavy objects close to the chest to avoid reinjury. Encourage them to return to work or resume normal activities as soon as possible, with neither bed rest nor exercise in the acute phase, and to participate in an aerobic exercise program when the pain has subsided. Heavy lifting, trunk twisting, and bodily vibration should be avoided in the acute phase.

What Not To Do:

Do not be too eager to use antispasm medicines. Many have sedative or anticholinergic side effects.

Do not be too eager to use antispasm medicines. Many have sedative or anticholinergic side effects.

Do not apply lumbar traction. It has not been proven to be any better than a placebo for relieving back pain. Do not provide lumbar orthotics, back braces, or lumbar cushions. They have no proven benefit. Lumbar supports have not been proven to reduce the incidence of low back pain in industrial workers and should not be routinely recommended for the prevention of low back pain.

Do not apply lumbar traction. It has not been proven to be any better than a placebo for relieving back pain. Do not provide lumbar orthotics, back braces, or lumbar cushions. They have no proven benefit. Lumbar supports have not been proven to reduce the incidence of low back pain in industrial workers and should not be routinely recommended for the prevention of low back pain.

Do not recommend bed rest for more than 2 days and only recommend it when the pain is severe. Bed rest does not increase the speed of recovery from acute low back pain and sometimes delays recovery.

Do not recommend bed rest for more than 2 days and only recommend it when the pain is severe. Bed rest does not increase the speed of recovery from acute low back pain and sometimes delays recovery.

Discussion

Low back pain affects men and women equally, with onset most often between the ages of 30 and 50 years. It is the most common and expensive cause of work-related disability in people who are younger than 45 years of age. A definitive diagnosis for nonradiating low back pain cannot be established in 85% of patients because of the weak associations between symptoms, pathologic changes, and imaging results. It can be generally assumed that much of this pain is secondary to musculoligamentous injury, degenerative changes in the spine, or a combination of the two. The approach discussed here is geared only to the management of acute injuries and flare-ups, from which most people recover on their own, which leaves only about 10% developing chronic problems. With acute pain, reassurance plus limited medication may be the most useful intervention. The 90% of back pain patients that become pain free are pain free within 3 months, and more than 90% of those patients recover spontaneously within 4 weeks. Even with diskogenic back pain or disk herniation with radicular pain, there are convincing data to support the nonoperative treatment of these patients in the absence of cauda equine syndrome or progressive neurologic deficit.

History and physical examination are essential to rule out serious pathologic conditions that can present as low back pain but require quite different treatment—aortic aneurysm, pyelonephritis, pancreatitis, abdominal tumors, pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and retroperitoneal or epidural abscess.

Older patients who experience radicular symptoms may have spinal stenosis, which may be accompanied by neurogenic claudication, a syndrome in which pain radiates down the legs, particularly when walking, and is often relieved by rest. This can be distinguished from vascular claudication, because the pain of neurogenic claudication starts even while the patient stands still. The pain is worsened by extension of the spine, which occurs with standing or walking, and improves with flexion, such as sitting or leaning forward.

The standard five-view radiograph study of the lumbosacral spine may entail 500 mrem of radiation, and yet, only 1 in 2500 lumbar spine plain films of adults below 50 years of age show an unexpected abnormality. In fact, many radiographic anomalies, such as spina bifida occulta, single-disk narrowing, spondylosis, facet joint abnormalities, and several congenital anomalies, are equally common in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. It is estimated that the gonadal dose of radiation absorbed from a five-view lumbosacral series is equivalent to that from 6 years of daily anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest films. The World Health Organization now recommends that oblique views be reserved for problems remaining after review of AP and lateral films. For simple cases of low back pain, even with radicular findings, both CT scans and MRI are overly sensitive and often reveal anatomic abnormalities that have no clinical significance. In one study of MRI scans, only 36% of asymptomatic patients had normal disks at all levels, whereas 64% had demonstrable disease (52% with at least one bulging disk, 27% with disk protrusion, and 1% with frank herniation). CT and MRI should be reserved for patients for whom there is a strong clinical suggestion of underlying infection, cancer, or persistent neurologic deficit. These tests have similar accuracy in detecting herniated disks and spinal stenosis, but MRI is more sensitive for infections, metastatic cancer, and rare neural tumors.

Although adults are more apt to have disk abnormalities, muscle strain, and degenerative changes associated with low back pain, athletically active adolescents are more likely to have posterior element derangements, such as stress fractures of the pars interarticularis. Early recognition of this spondylolysis and treatment by bracing and limitation of activity may prevent nonunion, persistent pain, and disability.

Although the true prevalence of posterior pelvic pain is unknown, researchers estimate that 15% to 30% of patients with low back pain have SIJ dysfunction. Radiation of pain down one or both legs may occur, but usually not below the knee or accompanied by positive straight-leg raising or neurologic deficit. Imaging is often not helpful. Radiographs, MRI, bone scan, and CT scans do not differentiate symptomatic from asymptomatic patients. Often SIJ pain presents as a progressive problem with fluctuations in symptoms. There is no gold standard for treatment. The recommendations noted above are dependent on the clinician’s experience and skills.

Malingering and drug-seeking are major psychological components to consider in patients who have frequent visits for back pain and whose responses seem overly dramatic or otherwise inappropriate. These patients may move around with little difficulty when they do not know they are being observed. They may complain of generalized superficial tenderness when you lightly pinch the skin over the affected lumbar area. When straight-leg raising is equivocally positive after testing the patient in a supine position, use distraction and reexamine the patient in the sitting position to see if the initial findings are reproduced. If there is suspicion that the patient’s pain is psychosomatic or nonorganic, use the axial loading test, in which the head of the standing person is gently pressed down on. This should not cause significant musculoskeletal back pain. The rotation test can also be performed, in which the patient stands with his arms at his sides. Hold his wrists next to his hips and turn his body from side to side, passively rotating his shoulders, trunk, and pelvis as a unit. This maneuver creates the illusion that the spinal rotation is being tested, but, in fact, the spinal axis has not been altered, and any complaint of back pain should be suspect.

Another technique that is easier to perform is the heel tap test. With the patient supine and with the hips and knees flexed to 90 degrees, suggest to the patient that the next test may cause low back pain, and then lightly tap the patient’s heel with the base of your hand. A complaint of sudden low back pain is an indication of malingering.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree