Low Back Pain

James P. Rathmell

Thomas T. Simopoulos

Zahid H. Bajwa

Shihab U. Ahmed

Pain is not just a stimulus that is transmitted over specific pathways but rather a complex perception, the nature of which depends not only on the intensity of the stimulus but on the situation in which it is experienced and, most importantly, on the affective or emotional state of the individual. Pain is to somatic stimulation as beauty is to a visual stimulus. It is a very subjective experience.

—Allan I. Basbaum, “Unlocking the Secrets of Pain: The Science,” Medical and Health Annual, Ellen Bernstein, ed., 1998

I. OVERVIEW

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common conditions presenting to both primary care physicians and to pain physicians. It has become a societal problem of unprecedented proportions, accounting for a large proportion of health care costs, as well as lost work days owing to the associated disability. In young adults, the problem often starts with an acute episode, triggered by trivial or substantial injury, which progresses insidiously to chronic pain. In older patients, degenerative changes are the more common cause of chronic back pain. It may be possible to “rescue” younger patients from a prolonged battle with chronic LBP and from reliance on medications by means of active intervention,

often with simple conservative measures, early in the course of the pain progression. An evidence-based algorithm for the management of adult LBP from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement is published by the National Guideline Clearinghouse. This guideline is a useful resource for physicians treating acute and chronic LBP, and provides the basis for the management approach suggested in this chapter (see Appendix II for useful Websites regarding guidelines for adults with low back pain).

often with simple conservative measures, early in the course of the pain progression. An evidence-based algorithm for the management of adult LBP from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement is published by the National Guideline Clearinghouse. This guideline is a useful resource for physicians treating acute and chronic LBP, and provides the basis for the management approach suggested in this chapter (see Appendix II for useful Websites regarding guidelines for adults with low back pain).

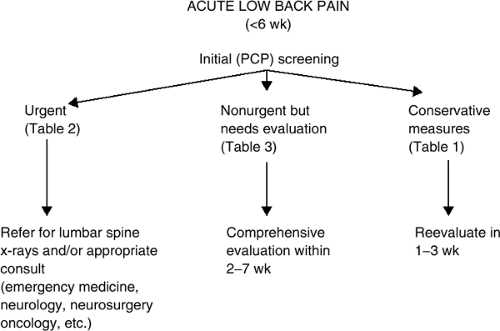

1. Acute Low Back Pain (Less than 6 Weeks’ Duration)

Ninety percent of patients with back pain improve within 4 to 6 weeks. During an early presentation, the patient should be encouraged to pursue conservative treatment measures (see Table 1) and to gradually resume normal activities, including return to work, once the pain reaches tolerable proportions. Patients should also be warned that a recurrence of the acute episode is likely and that more than 50% of patients with an acute back pain episode will experience other such episodes. Each acute episode, provided there is resolution between episodes, can be treated independently as a new acute episode.

In rare instances, the sudden onset of back pain has a serious pathologic basis. Serious pathology must be identified or excluded before assuming a more benign cause of pain (see Fig. 1). Initial screening must attempt to identify neurologic deterioration, infection, or tumor progression and to identify patients who require urgent intervention and/or urgent lumbar spine x-rays (see Table 2). The initial screen should also be used to identify patients who need further evaluation (within 2 to 7 weeks), although urgent intervention is not indicated (see Table 3).

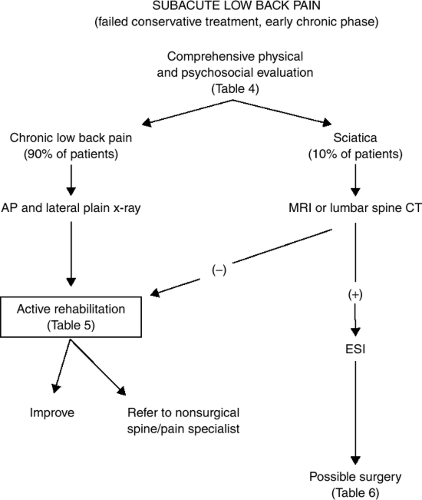

2. Subacute Low Back Pain

When the pain does not resolve with conservative measures, comprehensive physical and psychosocial evaluation is indicated (see Table 4). Nerve root compression is identified from history, physical examination, and imaging. If there is neural impingement, surgical assessment is warranted. Strong consideration should be given to performing a single or a series of fluoroscopically guided epidural steroid injections (ESIs) before embarking on

surgery (see Fig. 2). If there is no evidence of nerve impingement (90% of patients), the patient should be encouraged to undergo active rehabilitation (see Table 5). Effective rehabilitation at this stage provides the best hope of stalling the insidious course toward chronic pain. It is reasonable to make maximum use of all treatment options, including opioid medications and interventional procedures, toward the goal of restoration of function and of reduced reliance on medical intervention. The appearance of signs or symptoms of cauda equina syndrome or progressive or severe neurologic deficit calls for urgent surgical referral (see Table 6).

surgery (see Fig. 2). If there is no evidence of nerve impingement (90% of patients), the patient should be encouraged to undergo active rehabilitation (see Table 5). Effective rehabilitation at this stage provides the best hope of stalling the insidious course toward chronic pain. It is reasonable to make maximum use of all treatment options, including opioid medications and interventional procedures, toward the goal of restoration of function and of reduced reliance on medical intervention. The appearance of signs or symptoms of cauda equina syndrome or progressive or severe neurologic deficit calls for urgent surgical referral (see Table 6).

Table 1. Conservative treatment for acute low back pain | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 2. Initial screening of the patient with acute low back pain: identify features requiring urgent evaluation | |

|---|---|

|

Table 3. Initial screening of the patient with acute low back pain: identify features that will require further nonurgent evaluation (within 2–7 wk) | |

|---|---|

|

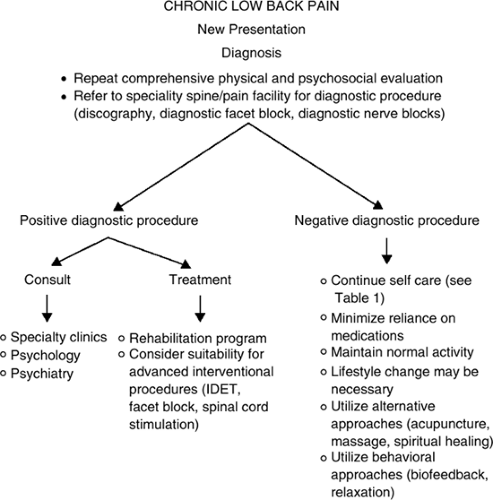

3. Chronic Low Back Pain

Many patients with chronic LBP manage without medical intervention, sometimes with the help of medical guidance or benign medical treatment (e.g., over-the-counter pain medication). Only patients with the most intransigent symptoms seek prolonged medical intervention, either from their primary care physicians or

from specialists. When the practitioner takes on a new patient, it will be necessary to repeat the initial screening (see Tables 2 and 3) and the comprehensive physical and psychosocial evaluation (see Table 4) so that any new pathology or psychopathology, if present, can be identified and appropriate specialty care can be sought (see Fig. 3). Chronic intransigent back pain is most appropriately treated with a multidisciplinary approach. Early psychological evaluation and treatment are helpful because motivational, psychological,

and social issues often dictate how appropriate and meaningful all future biologic interventions will be. An anatomic or other source of pain is sought, and a treatment program is established on this basis. Most often, a logical combination of medications and procedures is used to treat structural sources of pain. Rehabilitation through physical therapy is frequently employed as the next step to restore function. Integration of the various modalities used to treat chronic LBP is essential for optimal results. Ongoing medical, psychological, and rehabilitative intervention is often necessary to treat patients with severe debilitating chronic LBP.

from specialists. When the practitioner takes on a new patient, it will be necessary to repeat the initial screening (see Tables 2 and 3) and the comprehensive physical and psychosocial evaluation (see Table 4) so that any new pathology or psychopathology, if present, can be identified and appropriate specialty care can be sought (see Fig. 3). Chronic intransigent back pain is most appropriately treated with a multidisciplinary approach. Early psychological evaluation and treatment are helpful because motivational, psychological,

and social issues often dictate how appropriate and meaningful all future biologic interventions will be. An anatomic or other source of pain is sought, and a treatment program is established on this basis. Most often, a logical combination of medications and procedures is used to treat structural sources of pain. Rehabilitation through physical therapy is frequently employed as the next step to restore function. Integration of the various modalities used to treat chronic LBP is essential for optimal results. Ongoing medical, psychological, and rehabilitative intervention is often necessary to treat patients with severe debilitating chronic LBP.

Table 4. Comprehensive physical and psychosocial evaluation | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Figure 2. Algorithm for managing subacute low back pain of more than 6 weeks duration that has failed to improve with conservative treatment. |

Table 5. Active rehabilitation | |

|---|---|

|

II. EVALUATING THE PATIENT WITH BACK AND NECK PAIN

Important Principles

Serious causes of neck and back pain (e.g., infection, tumor, and trauma) are rare but must be excluded.

The etiology of pain in a considerable number of patients with back and neck pain may remain unknown. Nonspecific back or neck pain is a legitimate diagnosis.

History and physical examination have a limited role in the diagnosis of back and neck pain but are important in ruling out serious pathology.

It is important to distinguish pain limited to the axis of the spine from radicular pain and radiculopathy (i.e., loss of

sensation, weakness, and/or loss of deep tendon reflexes in a dermatomal distribution indicating nerve root dysfunction).

It is important to reassure patients with acute back and neck pain that most patients recover within weeks, without specific treatment.

Degenerative disc disease is the single most common cause for axial LBP.

Cervical facet joints are among the most common sources of axial neck pain.

Diagnostic local anesthetic blocks can be helpful in establishing an anatomic diagnosis.

1. General Principles

Patients with neck pain or LBP are commonly referred to a pain specialist for evaluation and treatment. In order to guide further diagnostic evaluation and to select proper treatment, several simple characteristics should first be determined by questioning the patient.

Duration of symptoms: acute versus chronic pain. Distinguishing acute back and neck pain (i.e., pain that has been present for days or weeks) from chronic pain (e.g., pain present for more than 6 weeks) will guide therapy. Most episodes of new-onset neck and back pain are self-limited and may require nothing more than symptomatic treatment and reassurance. Ninety percent of patients with back pain improve within 4 to 6 weeks. In contrast, patients with chronic axial LBP may present with radicular pain, signaling a new problem that may well require further evaluation. Finally, patients with a chronic, unchanging pattern of axial or radicular LBP, with or without a history of prior surgery, typically do not require further diagnostic evaluation, and attempts at treatment should be targeted toward long-term management.

Location of the pain: axial versus radicular pain. Although many patients will have pain along the axis of the spine (axial pain), as well as pain extending in to one or more extremity (radicular pain), differentiating axial from radicular pain is key to guiding therapy. Radicular pain suggests acute or chronic nerve root involvement. Axial pain suggests pain associated with disc degeneration, facet arthropathy, or other myofascial components of the spine.

Table 6. Indications for surgery

- Fit for surgery

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Progressive or severe neuromotor deficit (e.g., foot drop or functional muscle weakness such as hip flexion weakness or quadriceps weakness)

- Persistent neuromotor deficit after 4–6 wk of conservative treatment (does not include minor sensory changes or reflex changes)

- Chronic sciatica with positive straight leg raising for >4–6 wk

- Fit for surgery

Previous diagnostic evaluation. Understanding any diagnostic evaluation that has already been performed early in the course of obtaining the history and physical examination will help guide questioning and the examination. Attempts should be made to correlate findings on diagnostic imaging or electrodiagnostic testing with the patient’s report of pain and the findings during examination. Often, what appear to be important findings on diagnostic tests do not correlate with the pattern of pain reported by the patient. Further evaluation and treatment should always be directed toward the pain reported by the patient and not toward the results of diagnostic studies.

Previous spine surgery. “Failed back surgery syndrome” is a term that has worked its way into the medical literature. The term should not be used as if it were a specific diagnosis: every patient with failed back surgery syndrome is unique. To evaluate a patient who has neck pain or LBP following a spinal surgery, it is important to first understand exactly what surgery was performed. The characteristics of the pain preceding and after surgery, as well as the characteristics of the present pain, are the keys to guiding further evaluation and treatment. Following are descriptions of two patients with radicular pain and a history of back surgery. The first is a patient who underwent simple discectomy with complete relief of radicular pain several years earlier and who now presents with acute onset of radicular pain. He likely has a recurrent disc herniation and should be managed accordingly. In contrast, a patient with prior lumbar fusion and long-standing radicular pain likely has a chronic radiculopathy. This form of neuropathic pain should be managed with a very different approach.

2. Medical History

(i) General Medical History

Initial evaluation of any patient with back or neck pain should include a search for signs and symptoms pointing toward a potentially progressive or unstable underlying cause for the pain, including trauma, cancer, or infection (see Fig. 1).

Screening questions to detect cancer or to determine the status of patients with previous cancer: Any recent history of weight loss; history of prior cancer, including type of cancer, location, and treatment (breast, lung, renal cell, and prostate cancer have a particular proclivity for bone involvement) should be noted. Worsening pain at night, inability to attain relief at rest, and increased pain in the supine position raise suspicions for epidural spinal metastasis.

Screening questions for infectious causes of spinal pain: Any recent fever, chills, or other symptoms suggestive of an infectious process (e.g., cough, localized erythema or swelling, or antibiotic use); any history of immunosuppression, intravenous drug use, or recent spinal surgery (all are associated with a small but significant incidence of spinal infection) should be determined.

Screening questions for trauma: Any recent or significant trauma and the diagnostic evaluation that ensued (any patient with a significant mechanism of injury with onset of spinal pain should be evaluated for fracture or ligamentous instability) should be assessed.

Screening questions for vascular etiologies: Any history of abdominal pain or known abdominal aortic aneurysm or occlusion; history of peripheral vascular disease or claudication should be evaluated.

Screening questions for progressive or unstable neurologic status: Any worsening numbness or weakness in the extremities; bowel or bladder dysfunction (spinal cord or cauda equina compression may present first with urinary retention followed later by urinary and/or fecal incontinence); numbness extending in to both legs in a saddle distribution (perineal numbness bilaterally extending in to the sacral dermatomes suggests compression of the cauda equina) should be investigated.

Patients with suspected trauma and or progressive or unstable neurologic deficits should be managed urgently, either in collaboration with or by immediate referral to a spine surgeon.

(ii) Pain History

The pain history should document events surrounding the onset of pain. If a motor vehicle injury is the cause of pain, a thorough history including the use of a seat belt, single or multiple car involvement, and whether impact was from the rear or side of the vehicle can be useful in formulating a differential diagnosis. The pain history should also focus on the location of pain, its duration, radiation, character (e.g., deep, superficial, sharp, aching, burning, shooting, pins and needles, etc.), and worsening or relieving factors. When more than one site is involved, each pain complaint should be documented separately. The usefulness of elements in the pain history are as follows:

Location. The usefulness of location is obvious because it often narrows the search to a specific anatomic region. As described earlier, differentiating axial from radicular pain is among the most important features that will guide treatment.

Duration. Acute spinal pain is typically self-limited and requires only conservative management (see Table 1).

CHARACTER. The characteristics used by the patient to describe the pain can be very helpful in differentiating somatic pain from neuropathic pain, thereby guiding subsequent therapy. Somatic pain is usually described as aching and well localized. Neuropathic pain is often described as stabbing, shooting, or burning and may be accompanied by symptoms suggesting nerve dysfunction, such as a “pins and needles” sensation in a limited region. The hallmark of neuropathic pain is allodynia, or pain caused by a normally nonpainful stimulus (e.g., light touch to the affected region causes severe pain).

The pain history should also include previous interventions for pain, including medications, nerve blocks, surgery, physical therapy, and behavioral therapy. A review of previous medical records is often quite useful. A brief history of the patient’s activities of daily

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree