Long-term Opioid Therapy, Drug Abuse, and Addiction

Barth L. Wilsey

Scott Fishman

He jests at scars that never felt a wound.

—William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, Scene 2

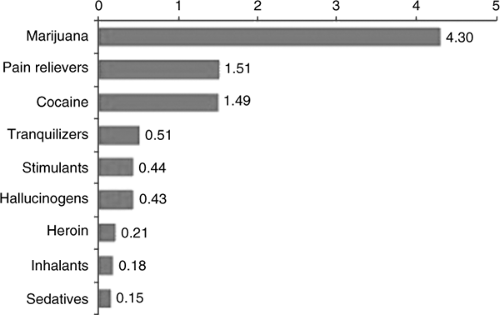

The utilization of opioids for chronic nonterminal pain (CNTP) remains controversial in the midst of growing awareness of the public health crisis of undertreated pain. Much of the controversy surrounding the prescribing of these medications is related to addiction and diversion. A national survey on drug use showed that the number of new nonmedical users of prescription pain relievers increased from 600,000 in 1990 to more than 2 million in 2001. This survey also showed that the prevalence of opioid abuse is now similar to that of cocaine and only second to that of marijuana (see Fig. 1). In March 2004, the Bush administration disclosed an ambitious plan, The President’s National Drug Control Strategy, to curb the growing menace of prescription drug abuse (i.e., analgesics, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives), which it stated, “now touches and harms more than 6 million Americans.” As part of its new policy, the administration has radically increased the funding for the control of prescription drug diversion (from $20 million to $138 million). A portion of the new funding will be directed toward reducing the illegal distribution of opioids, which are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the United States. The issue of how pain medications such as Oxycontin and Vicodin are being diverted has been regularly highlighted in the media. Although prescription drug abuse is a very serious problem, restraining legitimate prescription of opioid medications is unlikely to benefit the war on drugs but carries the likely risk of limiting necessary treatments for the individuals in need of the same.

Pain specialists and regulatory agencies are now actively debating how widely and readily pain medicines should be made available and whether these medicines should be prescribed only by specialists. At the same time, the Justice Department and Drug

Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the United States have become more aggressive in prosecuting doctors and pharmacists who they believe are inappropriately prescribing and dispensing prescription opioids. In recent years, a dozen or so health practitioners have been charged for their prescribing practices and several have been incarcerated. But patient advocates fear that the government has strayed from its mandate to recognize chronic pain, and they believe that such activities have had a “chilling effect” on appropriate prescribing practices. A middle ground must be found because it is imperative that patients with pain disorders are provided pain relief with opioid medications while drug diversion is curtailed.

Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the United States have become more aggressive in prosecuting doctors and pharmacists who they believe are inappropriately prescribing and dispensing prescription opioids. In recent years, a dozen or so health practitioners have been charged for their prescribing practices and several have been incarcerated. But patient advocates fear that the government has strayed from its mandate to recognize chronic pain, and they believe that such activities have had a “chilling effect” on appropriate prescribing practices. A middle ground must be found because it is imperative that patients with pain disorders are provided pain relief with opioid medications while drug diversion is curtailed.

Beyond regulatory scrutiny, treating pain has its own intrinsic difficulties stemming from the subjective nature of pain and the lack of conclusive objective markers. For instance, a history of substance abuse and the manifestation of prescription drug abuse are the two areas that require special attention because they pose special dilemmas for even the most experienced physician. This chapter explores the rational use of opioids for pain in relation to addiction and the monitoring of adherence to a treatment regimen. We hope to assist the clinician in developing an approach to opioid use that allows for vigilance for potentially adverse effects while suspending judgment and maintaining compassion in the service of effective analgesic intervention.

I. OPIOID USE IN THE ATMOSPHERE OF REGULATORY OVERSIGHT

Each state in the United States has its own regulations governing the prescription of controlled substances, and physicians prescribing these drugs should be familiar with the regulations in their state. The California triplicate prescription law was

established in 1939 for controlled substances and was the longest continuously running multiple copy prescription program in the United States. This program was replaced by tamper-resistant prescription pads in July 1, 2004, after it became apparent that the old law posed an unnecessary barrier to effective pain management. The rationale for multiple copy or serialized prescriptions was to provide a means of tracking these medications and thereby reducing their illicit use. Unfortunately, this law did not lead to a reduction in illicit drug trafficking. One possible reason for its ineffectiveness in reducing drug trafficking is that most drug abusers [i.e., those meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for the diagnosis of abuse of Schedule II drugs] probably obtain the drugs from sources other than their physician (by their own report). Although regulatory scrutiny seeks to prevent drug misuse associated with addiction, it also risks causing problems by its secondary disincentive for adequate pain management. Probably the most difficult question is what degree and type of regulation actually controls addiction and illicit drug use and what merely stands in the way of adequate pain treatment.

established in 1939 for controlled substances and was the longest continuously running multiple copy prescription program in the United States. This program was replaced by tamper-resistant prescription pads in July 1, 2004, after it became apparent that the old law posed an unnecessary barrier to effective pain management. The rationale for multiple copy or serialized prescriptions was to provide a means of tracking these medications and thereby reducing their illicit use. Unfortunately, this law did not lead to a reduction in illicit drug trafficking. One possible reason for its ineffectiveness in reducing drug trafficking is that most drug abusers [i.e., those meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for the diagnosis of abuse of Schedule II drugs] probably obtain the drugs from sources other than their physician (by their own report). Although regulatory scrutiny seeks to prevent drug misuse associated with addiction, it also risks causing problems by its secondary disincentive for adequate pain management. Probably the most difficult question is what degree and type of regulation actually controls addiction and illicit drug use and what merely stands in the way of adequate pain treatment.

Concerns over forgery, theft, excessive dosages, regulatory investigation, and addiction are cited as reasons why pharmacists are asked to uphold the “letter of the law” and are often reluctant to fill prescriptions for strong opioids. Prohibiting preferred drug regimens, restricting allotment to a 30-day maximum supply, and allowing only a 3-day emergency supply limits access to medications. It is not surprising that regulations and their ramifications have discouraged the prescribing of Schedule II drugs. Proposed electronic data transfer (EDT) of pharmacy information to centralized processing points is likely to be enacted in the near future, which will make it easier to identify unscrupulous physicians or patients with multiple prescribers. At the time of writing this chapter, the United States Congress was considering a national prescription monitoring program, and individual state governments were also considering modifying their approaches to drug abuse by adopting the revised Uniform Controlled Substances Act and/or by establishing state pain initiatives. Taken together, these programs may some day alleviate the need for regulations requiring restriction of pain prescriptions to a specific number of dosage units and/or using multiple copy prescriptions for controlled substances.

To avoid misinterpretation by regulatory agencies, physicians contemplating long-term opioid therapy for patients with chronic pain may be well advised to follow clear and consistent procedures to limit diversion of medications and drug abuse. At the very least, it is essential to perform a thorough initial history and physical examination, maintain a written treatment plan, and consult with knowledgeable colleagues, as needed. Minimum assessment should include a substance abuse, family, and psychiatric history. This is important because a history of substance abuse or a lifestyle where drug use is accepted or pervasive might indicate the need for additional measures before and after initiating opioid therapy. On the physical examination, one should note the patient’s affect and mood, evidence of loss of interest in personal grooming, needle marks, and/or any signs of intoxication

or withdrawal. If any of these signs are detected, one should proceed with a laboratory evaluation. This examination should include determination of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level for evidence of hepatocellular damage; red cell volume [mean cell volume (MCV)] for evaluation of megaloblastic anemia associated with alcoholism; in the case of positive signs of intravenous drug use, hepatitis B and C antigen titers; and a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) ribonucleic acid level. Because opioids never cure the underlying disorder that causes pain, consultation with a specialist in the area of the patient’s pain problem may be necessary when initiating opioid therapy. Although all these steps go a long way toward minimizing the risk of regulatory action for the patient and the clinician, the practitioner must also maintain the skills required for recognizing and responding to possible prescription drug abuse.

or withdrawal. If any of these signs are detected, one should proceed with a laboratory evaluation. This examination should include determination of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) level for evidence of hepatocellular damage; red cell volume [mean cell volume (MCV)] for evaluation of megaloblastic anemia associated with alcoholism; in the case of positive signs of intravenous drug use, hepatitis B and C antigen titers; and a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) ribonucleic acid level. Because opioids never cure the underlying disorder that causes pain, consultation with a specialist in the area of the patient’s pain problem may be necessary when initiating opioid therapy. Although all these steps go a long way toward minimizing the risk of regulatory action for the patient and the clinician, the practitioner must also maintain the skills required for recognizing and responding to possible prescription drug abuse.

II. PRESCRIPTION DRUG ABUSE

Careful assessment for possible prescription drug abuse is essential to limit a physician’s liability with regard to regulatory scrutiny. Many practitioners rely on their impression of the patient’s “drug-seeking behavior” for a rationale to refuse prescribing opioids. But there is controversy about the meaning of “drug-seeking behavior” because the term is often used pejoratively and signs of these behaviors can easily be based upon false impressions and may lead to false conclusions. One of the more common reasons for such labeling is that patients often self-escalate their opioid prescription and run out of medications early. They then call in for an early refill, disrupting the doctor’s practice with multiple phone calls or showing up at the office without an appointment. If such incidences are related to what has become known as pseudoaddiction, this occurs when a weak opioid (e.g., hydrocodone, codeine, and oxycodone) is given for a pain condition with an unrecognized need for a stronger medication. The solution involves rotating the patient from a weak opioid to a more potent opioid (e.g., slow-release morphine, slow-release oxycodone, transcutaneous fentanyl, and methadone). In other instances, the patient displays overt signs of drug-abuse with self-escalation of opioids that does not improve after opioid rotation. This scenario is complicated from the standpoint of clinical decision making because the patient may be taking medication for comorbid psychological conditions or may have developed opioid tolerance. Instances of abuse in patients who self-medicate with illicit substances are more clearly evident when urine toxicology reveals drugs of abuse. Alternatively, urine toxicology screening may demonstrate that the patients may not be taking their prescribed medications, suggesting the possibility of drug diversion. Interpretation of repeated prescription loss, multiple prescribers, or requests for early refills may range from simple manifestations of inadequate analgesia to signs of true abuse or diversion. Pseudoaddiction, a phenomenon first described in the patients with cancer, occurs when patients who are undertreated for their pain manifest a “drug-seeking behavior.” Unlike addiction, this behavior resolves once the pain is under

adequate control. Table 1 lists various aberrant behaviors that a patient may manifest in association with opioid use and abuse. Different responses are in order for these behaviors.

adequate control. Table 1 lists various aberrant behaviors that a patient may manifest in association with opioid use and abuse. Different responses are in order for these behaviors.

Table 1. Signs of prescription drug abuse | |

|---|---|

|

Unfortunately, the psychiatric literature on addiction and pain has been, and still remains, a source of confusion about addiction in the patient with chronic pain. To diagnose addictive disease, the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance dependence requires evidence of certain drug-seeking behaviors whereby “important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use.” But classic evidence of compulsive opioid use may be missing in patients with pain because opioid medication is being prescribed and is therefore readily available. In addition, patients with pain usually do not have to compromise their lifestyle or run the risk of endangering their lives by visiting seedy parts of town to obtain the prescribed opioid. Likewise, an illicit lifestyle (i.e., involvement in criminal activity and drug diversion) is generally not seen in patients with chronic pain. The form of addiction seen in the patient with pain is different from the type seen in the street addict. The subtle signs of prescription drug abuse (see Table 1) are deciphered from multiple observations and encounters.

If there is evidence of emotional distress accompanying prescription drug abuse, visits to a mental health provider should be encouraged to evaluate psychosocial issues. In cases of comorbid addiction and chronic pain requiring opioid therapy, it may be prudent to coordinate care with both a pain and an addiction specialist.

III. DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN PHYSICAL DEPENDENCE, TOLERANCE, AND ADDICTION

Recently, it has become possible to decipher the chemical “trigger zones” in which individual drugs of abuse initiate their habit-forming actions. Addiction and physical dependence are believed to be subserved by distinct anatomic areas within the central nervous system. Drugs belonging to different categories, such as heroin, cocaine, nicotine, alcohol, phencyclidine, and cannabis, activate a common reward circuitry in the brain. The area of

the brain in a rat that is responsible for opioid reward, the ventral tegmental dopaminergic area (mesolimbic pathway), is anatomically distant from the locus ceruleus, a noradrenergic area in the periventricular gray matter thought to have a major role in maintaining physical dependence. Several lines of evidence support the involvement of noradrenergic neurons in the development of withdrawal phenomena. Norepinephrine levels change in the brain following opioid dependence. Furthermore, administration of an α2 agonist, such as clonidine, or a β-antagonist, such as propranolol, reduces the severity of opioid withdrawal. The disparate anatomic and biochemical basis of addiction and withdrawal of the different drugs complement their differentiation in the clinical setting.

the brain in a rat that is responsible for opioid reward, the ventral tegmental dopaminergic area (mesolimbic pathway), is anatomically distant from the locus ceruleus, a noradrenergic area in the periventricular gray matter thought to have a major role in maintaining physical dependence. Several lines of evidence support the involvement of noradrenergic neurons in the development of withdrawal phenomena. Norepinephrine levels change in the brain following opioid dependence. Furthermore, administration of an α2 agonist, such as clonidine, or a β-antagonist, such as propranolol, reduces the severity of opioid withdrawal. The disparate anatomic and biochemical basis of addiction and withdrawal of the different drugs complement their differentiation in the clinical setting.

Despite the substantial differences between addiction and the pharmacologic states of physical dependence and tolerance, these concepts and labels are frequently misunderstood and are used inappropriately. Physical dependence is characterized as a physiologic state in which abrupt cessation of a drug results in a strong counterreaction called withdrawal. Such reactions are common to many drugs such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and caffeine. Physical dependence also occurs with drugs that have almost no abuse potential, such as clonidine. Opioid

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree