CHAPTER 115

Knee Sprain

Presentation

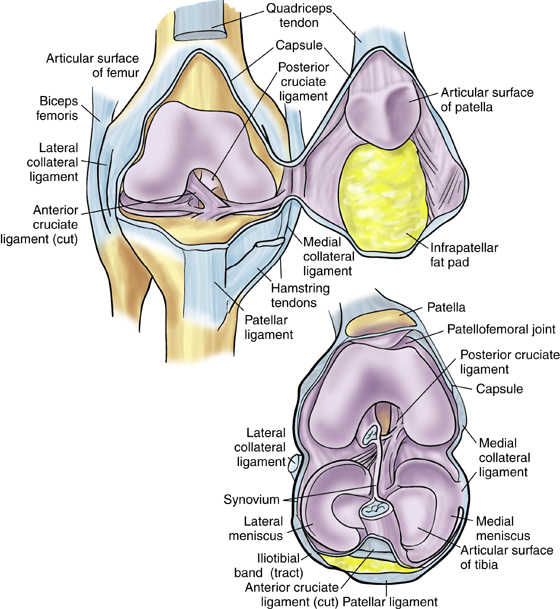

After twisting the knee from a slip and fall or sports injury, the patient complains of knee pain and variable ability to bear weight. There may be an effusion or spasm of the quadriceps, forcing the patient to hold the knee at 10 to 20 degrees of flexion. See Figure 115-1 for normal anatomy.

Figure 115-1 Knee joint structures. (From Miller MD, Hart JA, MacKnight JM: Essential orthopaedics. Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.)

With an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear, there will most likely be a noncontact injury involving a sudden deceleration (landing from a jump, cutting, or sidestepping), hyperextension, or twisting, as is common in basketball, football, and soccer. This may be accompanied by the sensation of a “pop,” followed by significant nonlocalizing pain and subsequent swelling and effusion. Significant injuries will have a positive Lachman examination.

The other common knee injury involves the medial collateral ligament (MCL). This may be torn with a direct blow to the lateral aspect of a partially flexed knee, such as being tackled from the side in football, or by an external rotational force on the tibia, which can occur in snow skiing when the tip of the skin is forced out laterally. There may also be an awareness of a “pop” during the injury, but unlike the ACL tear, it is localized to the medial knee, along with more focal pain and swelling. Significant injuries cause laxity of the MCL with valgus stress testing at 30 degrees of flexion.

The meniscus can be torn acutely with a sudden twisting injury of the knee while the knee is partially flexed, such as may occur when a runner suddenly changes direction or when the foot is firmly planted, the tibia is rotated, and the knee is forcefully extended. Pain along the joint line is felt immediately, and there is often a mild effusion with tenderness to palpation along either that medial or lateral joint line. There may be a positive McMurray test.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries occur with forced hyperflexion, as can occur in high-contact sports, such as football and rugby. Tears of the PCL can also occur with a posterior blow to the proximal tibia of a flexed knee, as occurs with dashboard injuries to the knee during motor vehicle collisions. Hyperextension, most often with an associated varus or valgus force, can also cause PCL injury. There is no report of a tear or pop, only vague symptoms, such as unsteadiness or discomfort. There is commonly a mild to moderate knee effusion, and a significant injury will have a positive posterior drawer test, and a posterior sag sign will be present.

Injury of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is much less common than injury of the MCL. This usually results from varus stress to the knee, as occurs when a runner plants his foot and then turns toward the ipsilateral knee or when there is a direct blow to the anteromedial knee. The patient reports acute onset of lateral knee pain that requires prompt cessation of activity.

What To Do:

If there is going to be any delay in examining the knee, provide ice, a compression dressing, and elevation above the level of the heart.

If there is going to be any delay in examining the knee, provide ice, a compression dressing, and elevation above the level of the heart.

For severe pain, provide immediate analgesia with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Motrin), 800 mg PO, along with a narcotic such as oxycodone (Percocet, Tylox). Parenteral narcotics may be required.

For severe pain, provide immediate analgesia with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Motrin), 800 mg PO, along with a narcotic such as oxycodone (Percocet, Tylox). Parenteral narcotics may be required.

Ask about the mechanism of injury, which is often the key to the diagnosis. The position of the joint and direction of traumatic force dictates which anatomic structures are at greatest risk for injury. The patient can usually re-create exactly what happened by using the uninjured knee to demonstrate.

Ask about the mechanism of injury, which is often the key to the diagnosis. The position of the joint and direction of traumatic force dictates which anatomic structures are at greatest risk for injury. The patient can usually re-create exactly what happened by using the uninjured knee to demonstrate.

Obtain information about associated symptoms. Knee buckling/instability with pivoting or walking is associated with ACL tear. A knee-joint effusion within 4 to 6 hours of injury suggests an intra-articular injury, such as ACL, meniscus, or osteochondral fracture. Sensations of locking or catching inside the knee may be associated with meniscal tears.

Obtain information about associated symptoms. Knee buckling/instability with pivoting or walking is associated with ACL tear. A knee-joint effusion within 4 to 6 hours of injury suggests an intra-articular injury, such as ACL, meniscus, or osteochondral fracture. Sensations of locking or catching inside the knee may be associated with meniscal tears.

During inspection and examination of the injured knee, comparison with the normal knee is important. Initiate the examination by focusing first on the leg that is healthy. This helps to create trust and allows the patient to relax for a more accurate examination. Inspect the knee for swelling, ecchymosis, malalignment, or disruption of skin. Palpate the bony and ligamentous structure on the medial and lateral aspect of the knee, and palpate along both joints to elicit any point tenderness. With the patient supine, feel for an effusion and discomfort with patellar motion. Determine if there is any crepitus or limitation in range of motion by gently attempting to fully flex and extend the knee. Look for injuries of the back and pelvis. Check hip flexion, extension, and rotation. Thump the sole of the foot as an axial loading clue to a tibia or fibula fracture.

During inspection and examination of the injured knee, comparison with the normal knee is important. Initiate the examination by focusing first on the leg that is healthy. This helps to create trust and allows the patient to relax for a more accurate examination. Inspect the knee for swelling, ecchymosis, malalignment, or disruption of skin. Palpate the bony and ligamentous structure on the medial and lateral aspect of the knee, and palpate along both joints to elicit any point tenderness. With the patient supine, feel for an effusion and discomfort with patellar motion. Determine if there is any crepitus or limitation in range of motion by gently attempting to fully flex and extend the knee. Look for injuries of the back and pelvis. Check hip flexion, extension, and rotation. Thump the sole of the foot as an axial loading clue to a tibia or fibula fracture.

Document any effusion, discoloration, heat, deformity, or loss of function, circulation, sensation, or movement.

Document any effusion, discoloration, heat, deformity, or loss of function, circulation, sensation, or movement.

Stress the four major knee ligaments, comparing the injured with the uninjured knee to determine if there is any instability. A complete knee examination will help to detect isolated ligamentous injuries but will also help the examiner find coexisting injuries.

Stress the four major knee ligaments, comparing the injured with the uninjured knee to determine if there is any instability. A complete knee examination will help to detect isolated ligamentous injuries but will also help the examiner find coexisting injuries.

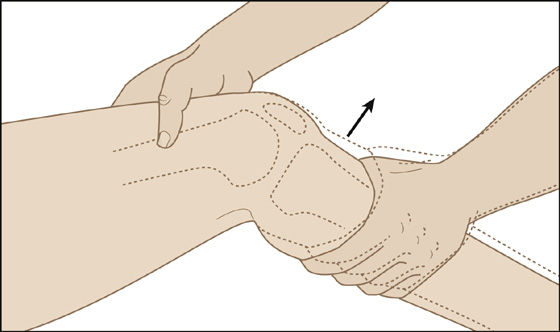

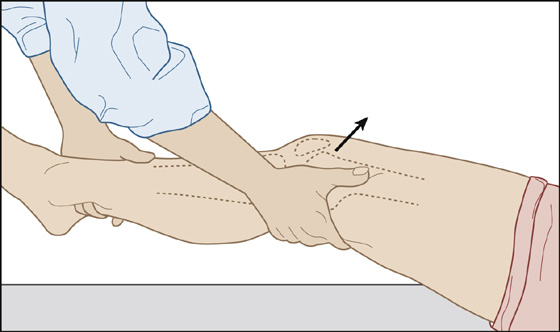

Perform a Lachman test to diagnose injury of the ACL (Figure 115-2). With the knee flexed 20 to 30 degrees, place one hand on the proximal tibia and the other on the distal femur, with the patient’s heel on the examination table. Stabilize the femur, grasp the tibia, and pull it anteriorly with a brisk tug. ACL tears will have increased anterior translation, at least 3 mm greater than the noninjured side, and a soft or nonexistent end point.

Perform a Lachman test to diagnose injury of the ACL (Figure 115-2). With the knee flexed 20 to 30 degrees, place one hand on the proximal tibia and the other on the distal femur, with the patient’s heel on the examination table. Stabilize the femur, grasp the tibia, and pull it anteriorly with a brisk tug. ACL tears will have increased anterior translation, at least 3 mm greater than the noninjured side, and a soft or nonexistent end point.

Figure 115-2 The Lachman test.

Test MCL stability with the valgus stress test (Figure 115-3). With the knee still flexed 20 to 30 degrees, grasp the tibia distally to stabilize the lower leg, then apply direct, firm pressure in a medial direction from the lateral femoral condyle. Pain in the location of the MCL during valgus stressing, but no laxity, is called a grade I sprain. Grade II sprains have some laxity during valgus load; however, there is still a solid end point. When there is a soft or nonexistent end point, this is called a grade III MCL sprain, which represents a complete tear of the ligament. Repeat valgus stress testing in full extension. If there is joint laxity when the knee is locked in full extension, there is a strong possibility of an accompanying ACL, posterior oblique ligament, or posteromedial capsular tear.

Test MCL stability with the valgus stress test (Figure 115-3). With the knee still flexed 20 to 30 degrees, grasp the tibia distally to stabilize the lower leg, then apply direct, firm pressure in a medial direction from the lateral femoral condyle. Pain in the location of the MCL during valgus stressing, but no laxity, is called a grade I sprain. Grade II sprains have some laxity during valgus load; however, there is still a solid end point. When there is a soft or nonexistent end point, this is called a grade III MCL sprain, which represents a complete tear of the ligament. Repeat valgus stress testing in full extension. If there is joint laxity when the knee is locked in full extension, there is a strong possibility of an accompanying ACL, posterior oblique ligament, or posteromedial capsular tear.

Figure 115-3 Valgus stress test.

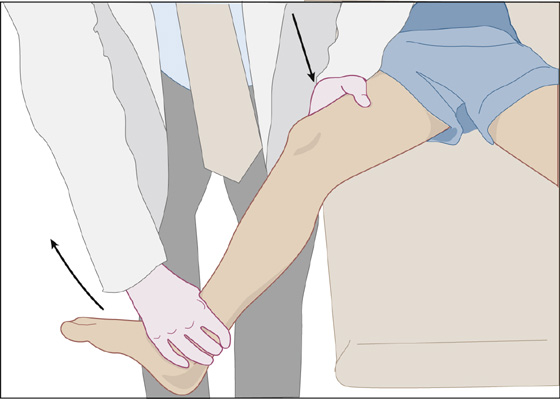

Test the integrity of the PCL and posterior capsule with the posterior drawer test (Figure 115-4). The test is performed with the patient supine and the hip flexed to 45 degrees. Flex the knee to 90 degrees and apply firm, direct pressure in a posterior direction to the anteroproximal tibia with your thumbs located on the medial and lateral joint lines. If the force displaces the anterior superior tibial border beyond the medial femoral condyle, this suggests a complete PCL injury; posterior displacement of the tibia more than 5 mm posterior to the femur suggests a combined PCL and posterolateral-corner injury. Look for increased posterior displacement of the tibia and a soft or mushy end point. When the knee is in 90 degrees of flexion, the proximal tibia normally sits about 10 mm anterior to the femoral condyles. If no step-off is present, a posterior sag sign exists and is also associated with PCL injury. These tests may be difficult to perform if there is a large effusion. Fifteen percent of patients with posterolateral knee injuries have a common peroneal nerve injury. It is important to ask patients about sensory changes or muscle weakness and to examine ankle dorsiflexion and great-toe extension.

Test the integrity of the PCL and posterior capsule with the posterior drawer test (Figure 115-4). The test is performed with the patient supine and the hip flexed to 45 degrees. Flex the knee to 90 degrees and apply firm, direct pressure in a posterior direction to the anteroproximal tibia with your thumbs located on the medial and lateral joint lines. If the force displaces the anterior superior tibial border beyond the medial femoral condyle, this suggests a complete PCL injury; posterior displacement of the tibia more than 5 mm posterior to the femur suggests a combined PCL and posterolateral-corner injury. Look for increased posterior displacement of the tibia and a soft or mushy end point. When the knee is in 90 degrees of flexion, the proximal tibia normally sits about 10 mm anterior to the femoral condyles. If no step-off is present, a posterior sag sign exists and is also associated with PCL injury. These tests may be difficult to perform if there is a large effusion. Fifteen percent of patients with posterolateral knee injuries have a common peroneal nerve injury. It is important to ask patients about sensory changes or muscle weakness and to examine ankle dorsiflexion and great-toe extension.

Figure 115-4 Posterior drawer test.

Test LCL stability with the varus stress test (Figure 115-5), pressing laterally on the medial femoral condyle with the knee flexed to 20 to 30 degrees and in full extension. Grading is the same as for MCL sprains. Lateral joint line opening in full extension typically indicates a multiligament injury. Grade III tears are indicative of complete LCL tear and have a high association with posterolateral corner injury or cruciate tears. If there is varus laxity, also check the function of the peroneal nerve by asking the patient to dorsiflex the big toe.

Test LCL stability with the varus stress test (Figure 115-5), pressing laterally on the medial femoral condyle with the knee flexed to 20 to 30 degrees and in full extension. Grading is the same as for MCL sprains. Lateral joint line opening in full extension typically indicates a multiligament injury. Grade III tears are indicative of complete LCL tear and have a high association with posterolateral corner injury or cruciate tears. If there is varus laxity, also check the function of the peroneal nerve by asking the patient to dorsiflex the big toe.

Figure 115-5 Varus stress test. (The valgus stress test is the opposite of this test.)

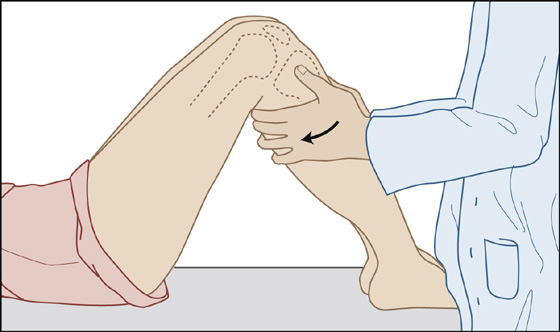

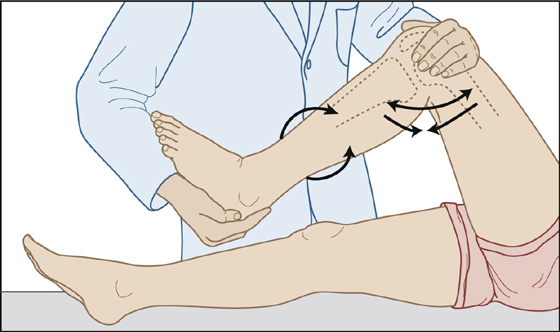

Examine for an injury to the medial or lateral meniscal cartilage with the McMurray test (Figure 115-6). With the patient supine, hold the knee anteriorly at the femoral condyle with one hand, fingers positioned along the joint line, and while applying a valgus force to the knee, hold the foot with the other hand. Then, while externally rotating the lower leg, fully flex the knee and hip, slowly extend, and then repeat with the lower leg internally rotated. Pain associated with audible sounds or palpable crepitus suggests a tear of the meniscus. This test may be difficult to complete if there is acute pain and muscle spasm.

Examine for an injury to the medial or lateral meniscal cartilage with the McMurray test (Figure 115-6). With the patient supine, hold the knee anteriorly at the femoral condyle with one hand, fingers positioned along the joint line, and while applying a valgus force to the knee, hold the foot with the other hand. Then, while externally rotating the lower leg, fully flex the knee and hip, slowly extend, and then repeat with the lower leg internally rotated. Pain associated with audible sounds or palpable crepitus suggests a tear of the meniscus. This test may be difficult to complete if there is acute pain and muscle spasm.

Figure 115-6 The McMurray test.

A negative test does not rule out a meniscal tear. Tenderness from meniscal tears is localized along the joint line, most prominently at or posterior to the collateral ligament. The medial meniscus is more susceptible to injury.

A negative test does not rule out a meniscal tear. Tenderness from meniscal tears is localized along the joint line, most prominently at or posterior to the collateral ligament. The medial meniscus is more susceptible to injury.

Palpate the patella and head of the fibula, looking for tenderness associated with fracture.

Palpate the patella and head of the fibula, looking for tenderness associated with fracture.

Assess for effusion by placing a finger lightly on the patella with the knee relaxed and fully extended and, with the other hand, gently pinching the soft tissue on both sides of the patella, feeling for a fluid wave. In the presence of an intra-articular effusion, the patella can also be bounced or balloted against the underlying femoral condyle.

Assess for effusion by placing a finger lightly on the patella with the knee relaxed and fully extended and, with the other hand, gently pinching the soft tissue on both sides of the patella, feeling for a fluid wave. In the presence of an intra-articular effusion, the patella can also be bounced or balloted against the underlying femoral condyle.

Radiographs to rule out fracture may be deferred or avoided if the patient does not meet one of the following Ottawa knee rules:

Radiographs to rule out fracture may be deferred or avoided if the patient does not meet one of the following Ottawa knee rules:

Fifty-five years of age or older

Fifty-five years of age or older

Tenderness at the head of the fibula

Tenderness at the head of the fibula

Isolated tenderness of the patella

Isolated tenderness of the patella

Inability to flex the knee to 90 degrees

Inability to flex the knee to 90 degrees

Inability to bear weight (four steps) both immediately after injury and at initial physical assessment

Inability to bear weight (four steps) both immediately after injury and at initial physical assessment

These criteria do not apply to patients younger than 5 years of age or patients with an altered level of consciousness, multiple painful injuries, paraplegia, or diminished limb sensation.

These criteria do not apply to patients younger than 5 years of age or patients with an altered level of consciousness, multiple painful injuries, paraplegia, or diminished limb sensation.

Minor (grade I) sprains that do not exhibit any joint instability or intra-articular effusion can be treated with rest, elevation, and, if comfort is improved, ice (20-minute periods three or four times a day for 3 days), and acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) (ibuprofen, naproxen). The patient can usually return to his previous activities as rapidly as pain allows. Provide follow-up if symptoms do not improve in 5 to 7 days.

Minor (grade I) sprains that do not exhibit any joint instability or intra-articular effusion can be treated with rest, elevation, and, if comfort is improved, ice (20-minute periods three or four times a day for 3 days), and acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) (ibuprofen, naproxen). The patient can usually return to his previous activities as rapidly as pain allows. Provide follow-up if symptoms do not improve in 5 to 7 days.

Moderate (grade II) and severe (grade III) sprains with partial or complete ligament tears, meniscal tears, joint effusion, or instability should be treated with rest and ice, as above, but also immobilized with a bulky compression splint or knee immobilizer and made non–weight-bearing with crutches. Patients should keep the leg elevated above the heart as much as possible to minimize swelling. Narcotic analgesics may be added to acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs, and patients should be referred for orthopedic assessment within 5 to 7 days.

Moderate (grade II) and severe (grade III) sprains with partial or complete ligament tears, meniscal tears, joint effusion, or instability should be treated with rest and ice, as above, but also immobilized with a bulky compression splint or knee immobilizer and made non–weight-bearing with crutches. Patients should keep the leg elevated above the heart as much as possible to minimize swelling. Narcotic analgesics may be added to acetaminophen and/or NSAIDs, and patients should be referred for orthopedic assessment within 5 to 7 days.

Instruct the patient that additional injuries may become apparent as the spasm and effusion abate.

Instruct the patient that additional injuries may become apparent as the spasm and effusion abate.

What Not To Do:

Do not assume that a negative radiograph means a major injury does not exist.

Do not assume that a negative radiograph means a major injury does not exist.

Do not rely on MRI to assess all injured knees. MRI is not cost-effective or superior to clinical assessment in accuracy. MRI is a useful tool for assessing a knee before operative intervention, especially with posterolateral corner injuries, which may require the reconstruction of multiple ligaments and the lateral meniscus.

Do not rely on MRI to assess all injured knees. MRI is not cost-effective or superior to clinical assessment in accuracy. MRI is a useful tool for assessing a knee before operative intervention, especially with posterolateral corner injuries, which may require the reconstruction of multiple ligaments and the lateral meniscus.

Do not inject or prescribe corticosteroids for acute knee injuries. These drugs may retard soft tissue healing.

Do not inject or prescribe corticosteroids for acute knee injuries. These drugs may retard soft tissue healing.

Do not miss vascular injuries with bicruciate ligament injuries. These injuries are equivalent to knee dislocations with regard to mechanism of injury, severity of ligamentous injury, and frequency of major arterial injuries.

Do not miss vascular injuries with bicruciate ligament injuries. These injuries are equivalent to knee dislocations with regard to mechanism of injury, severity of ligamentous injury, and frequency of major arterial injuries.

Discussion

The ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL, make up the main static stabilizers of the knee. Together, the four ligaments enable the knee to function as a complex hinge joint, with rotational capabilities that allow the tibia to rotate internally and glide posteriorly on the femoral condyles during flexion and to rotate externally 15 to 30 degrees during extension.

The menisci are crescent-shaped cartilaginous structures that provide a cushioning congruous surface for the transmission of 50% of the axial forces across the knee joint. The menisci increase joint stability, facilitate nutrition, and provide lubrication and shock absorption for the articular cartilage.

Most patients with a knee injury suffer soft tissue damage, including ligament, tendon, meniscal cartilage, and muscle tears. In most cases, plain radiographs do little to aid diagnosis of soft tissue injury. Plain radiographs can show findings suggestive of ACL injury, such as an avulsion of the lateral capsule, known as a Segond fracture or a tibial spine avulsion. They can also show subtle fractures of the posterior tibial plateau or associated fibular head avulsion fractures. However, clinicians must rely on physical examination to identify patients with serious knee injuries that require splinting and/or orthopedic referral.

Joint aspiration of hemarthrosis to reduce severe pain should be reserved for patients with very large or tense effusions and should be performed with sterile technique. Fat globules in bloody joint fluid suggest occult fracture.

Conservative treatment versus surgical reconstruction is the main treatment decision when managing an ACL tear. ACL reconstruction is the preferred treatment for adolescents and most young adults who are unwilling to modify their physical activity levels. In older patients, there is support for both conservative and operative treatment. Patients with a sedentary or low-impact lifestyle are ideal candidates for conservative or nonoperative management. Patients who compete in jumping or cutting sports are likely to benefit from ACL reconstruction.

A medial stabilizing brace can be prescribed for grade II and grade III MCL injuries. Select the longest brace that fits the patient to provide maximum MCL protection. Currently, surgical repair of a grade III MCL tear is reserved for the patient who has associated damage to the ACL or meniscus.

A long-leg knee brace can be prescribed for grade II LCL sprains. One such brace is the extension locking splint, which allows a full range of motion in flexion and extension, but will give support to varus and valgus stresses. This brace can also be locked in extension for ambulation during the first 1 to 2 weeks of rehabilitation.

The standard now for grade III LCL and posterolateral corner injuries with or without PCL involvement is surgical repair, and more often reconstruction, which should be completed within the first 1 to 2 weeks following the injury.

In general, a patient who has had a knee injury can be given the go-ahead to resume sports activities when examination demonstrates that the cruciate and collateral ligaments are intact, the knee is capable of moving from full extension to flexion of 120 degrees, and there is no effusion. The patient’s pain should be markedly diminished, and there should be no locking, instability, or limp.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree