CHAPTER 20

Iritis

(Acute Anterior Uveitis)

Presentation

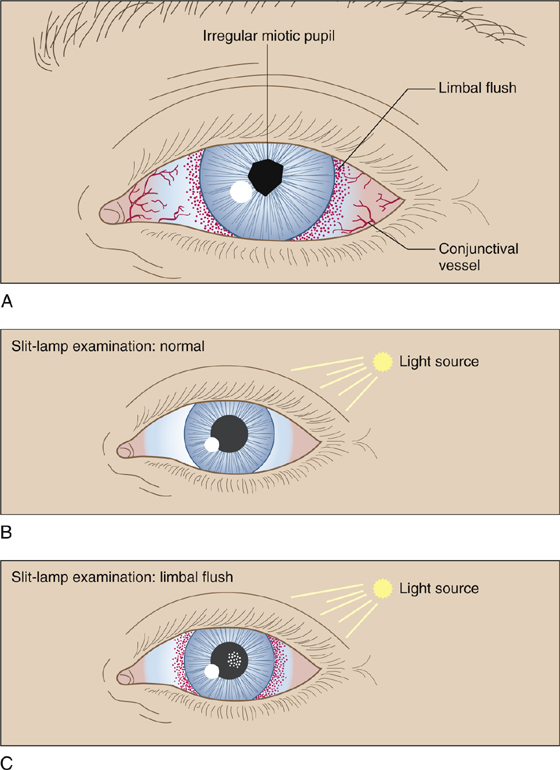

The patient usually complains of the onset over hours or days of unilateral eye pain, blurred vision, and photophobia. He may have noticed a pink-colored eye for a few days, suffered mild to moderate trauma during the previous day or two, or experienced no overt eye problems. There may be tearing, but there is usually no discharge. Eye pain is not markedly relieved after instillation of a topical anesthetic. On inspection of the junction of the cornea and conjunctiva (the corneal limbus), a circumcorneal injection, which on closer inspection is a tangle of fine ciliary vessels, is visible through the white sclera. This limbal blush or ciliary flush is usually the earliest sign of iritis. A slit lamp with 10× magnification may help with identification, but the injection is usually evident merely on close inspection. As the iritis becomes more pronounced, the iris and ciliary muscles go into spasm, producing an irregular, poorly reactive, constricted pupil and a lens that will not focus. The slit-lamp examination should demonstrate white blood cells or light reflection from a protein exudate in the clear aqueous humor of the anterior chamber (cells and flare) (Figure 20-1).

Figure 20-1 A, Early signs of iritis. B, Normal reflection of pinhole light from the cornea and iris. C, Cells and flare from iritis in highlight appear similar to what is seen when a light beam is projected through a dark, smoky room.

What To Do:

Using topical anesthesia, perform a complete eye examination that includes best-corrected visual acuity assessment, pupil reflex examination, funduscopy, slit-lamp examination of the anterior chamber (including pinhole illumination to bring out cells and flare), and fluorescein staining to detect any corneal lesion.

Using topical anesthesia, perform a complete eye examination that includes best-corrected visual acuity assessment, pupil reflex examination, funduscopy, slit-lamp examination of the anterior chamber (including pinhole illumination to bring out cells and flare), and fluorescein staining to detect any corneal lesion.

Shining a bright light in the normal eye should cause pain in the symptomatic eye (consensual photophobia). Visual acuity may be decreased in the affected eye.

Shining a bright light in the normal eye should cause pain in the symptomatic eye (consensual photophobia). Visual acuity may be decreased in the affected eye.

Attempt to ascertain the cause of the iritis. (Is it generalized from a corneal insult or conjunctivitis, a late sequela of blunt trauma, infectious, or autoimmune?) Approximately 50% of patients have idiopathic uveitis that is not associated with any other pathologic syndrome. Idiopathic iritis should be suspected when there is acute onset of pain and photophobia in a healthy individual who does not have systemic disease.

Attempt to ascertain the cause of the iritis. (Is it generalized from a corneal insult or conjunctivitis, a late sequela of blunt trauma, infectious, or autoimmune?) Approximately 50% of patients have idiopathic uveitis that is not associated with any other pathologic syndrome. Idiopathic iritis should be suspected when there is acute onset of pain and photophobia in a healthy individual who does not have systemic disease.

When a patient presents with a first occurrence of unilateral acute anterior uveitis and the history and physical examination are unremarkable, there is no need for any diagnostic workup for systemic disease. With recurrent or bilateral acute uveitis, with or without suspicious findings historically or on physical examination, a diagnostic workup should be initiated at the time of the visit or by the ophthalmologist on follow-up. Unless history and physical examination indicate otherwise, this should include a complete blood count (CBC), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a Lyme titer, and a chest radiograph.

When a patient presents with a first occurrence of unilateral acute anterior uveitis and the history and physical examination are unremarkable, there is no need for any diagnostic workup for systemic disease. With recurrent or bilateral acute uveitis, with or without suspicious findings historically or on physical examination, a diagnostic workup should be initiated at the time of the visit or by the ophthalmologist on follow-up. Unless history and physical examination indicate otherwise, this should include a complete blood count (CBC), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), a Lyme titer, and a chest radiograph.

When possible, determine intraocular pressure, which may be normal or slightly decreased in the acute phase because of decreased aqueous humor production. An elevated pressure should alert you to the possibility of acute glaucoma.

When possible, determine intraocular pressure, which may be normal or slightly decreased in the acute phase because of decreased aqueous humor production. An elevated pressure should alert you to the possibility of acute glaucoma.

Explain to the patient the potential severity of the problem; this is no routine conjunctivitis, but a process that can develop into blindness. You can reassure him that the prognosis is good with appropriate treatment.

Explain to the patient the potential severity of the problem; this is no routine conjunctivitis, but a process that can develop into blindness. You can reassure him that the prognosis is good with appropriate treatment.

Arrange for ophthalmologic follow-up within 24 hours, with the ophthalmologist agreeing to the treatment as follows:

Arrange for ophthalmologic follow-up within 24 hours, with the ophthalmologist agreeing to the treatment as follows:

Dilate the pupil and paralyze ciliary accommodation with 1% cyclopentolate (Cyclogyl) drops, which will relieve the pain of the muscle spasm and keep the iris away from the lens, where miosis and inflammation might cause adhesions (posterior synechiae). For a more prolonged effect (homatropine is the agent of choice for uveitis), instill a drop of homatropine 5% (Isopto Homatropine) before discharging the patient.

Dilate the pupil and paralyze ciliary accommodation with 1% cyclopentolate (Cyclogyl) drops, which will relieve the pain of the muscle spasm and keep the iris away from the lens, where miosis and inflammation might cause adhesions (posterior synechiae). For a more prolonged effect (homatropine is the agent of choice for uveitis), instill a drop of homatropine 5% (Isopto Homatropine) before discharging the patient.

Suppress the inflammation with topical steroids, such as 1% prednisolone (Inflamase, Pred Forte), 1 drop qid.

Suppress the inflammation with topical steroids, such as 1% prednisolone (Inflamase, Pred Forte), 1 drop qid.

Newer formulations of corticosteroids, such as loteprednol 0.2% (Alrex) or 0.5% (Lotemax), 5 mL, 1 drop qid, may reduce the risk for raising intraocular pressure, but they also appear to be less efficacious in reducing inflammation.

Newer formulations of corticosteroids, such as loteprednol 0.2% (Alrex) or 0.5% (Lotemax), 5 mL, 1 drop qid, may reduce the risk for raising intraocular pressure, but they also appear to be less efficacious in reducing inflammation.

Prescribe oral pain medicine if necessary, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if tolerated.

Prescribe oral pain medicine if necessary, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if tolerated.

Ensure that the patient is seen the next day for follow-up.

Ensure that the patient is seen the next day for follow-up.

What Not To Do:

Do not let the patient shrug off his “pink eye” and neglect to obtain follow-up, even if he is feeling better, because of the real possibility of permanent visual impairment.

Do not let the patient shrug off his “pink eye” and neglect to obtain follow-up, even if he is feeling better, because of the real possibility of permanent visual impairment.

Do not give antibiotics unless there is evidence of a bacterial infection.

Do not give antibiotics unless there is evidence of a bacterial infection.

Do not overlook a possible penetrating foreign body as the cause of the inflammation.

Do not overlook a possible penetrating foreign body as the cause of the inflammation.

Do not assume the diagnosis of acute iritis until other causes of red eye have been considered and ruled out.

Do not assume the diagnosis of acute iritis until other causes of red eye have been considered and ruled out.

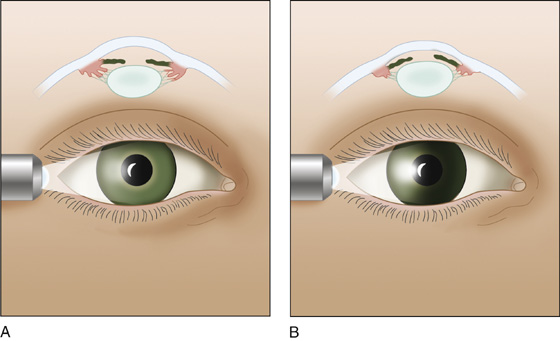

Avoid dilating an eye with a shallow anterior chamber and precipitating acute angle-closure glaucoma (Figure 20-2).

Avoid dilating an eye with a shallow anterior chamber and precipitating acute angle-closure glaucoma (Figure 20-2).

Figure 20-2 A, Normal iris. B, Domed iris casts a shadow. The shallow anterior chamber is prone to acute angle-closure glaucoma if the pupil is dilated.

Discussion

Physical examination should focus on visual acuity; presence of pain; location of redness; shape, size, and reaction of the pupil; and the intraocular pressure, if it can be obtained safely. If a slit lamp is available, the diagnosis can be made more definitively.

Uveitis is defined as inflammation of one or all parts of the uveal tract. Components of the uveal tract include the iris, the ciliary body, and the choroids. Uveitis may involve all areas of the uveal tract and can be acute or chronic; however, it is the acute form—confined to the iris and anterior chamber (iritis) or the iris, anterior chamber, and ciliary body (iridocyclitis)—that is most commonly seen in an ED or urgent care facility.

Iritis (or iridocyclitis) represents a potential threat to vision and requires emergency treatment and expert follow-up. The inflammatory process in the anterior eye can opacify the anterior chamber, deform the iris or lens, scar them together, or extend into adjacent structures. Posterior synechiae can potentiate cataracts and glaucoma. Treatment with topical steroids is the mainstay of therapy for acute anterior uveitis, but this therapy can backfire if the process is caused by an infection (especially herpes keratitis); therefore the slit-lamp examination is especially useful. Topical steroids alone can also contribute to cataract formation as well as the development of glaucoma.

Iritis may have no apparent cause, may be related to recent trauma, or may be associated with an immune reaction. In addition to association with infections such as herpes, Lyme disease, and microbial keratitis, uveitis is found in association with autoimmune disorders, such as ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter syndrome (conjunctivitis, urethritis, and polyarthritis), psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease, as well as in association with underlying malignancies.

Sometimes an intense conjunctivitis or keratitis (see Chapters 14 and 15) may produce some sympathetic limbal flush, which will resolve as the primary process resolves and requires no additional treatment. A more definite, but still mild, iritis may resolve with administration of cycloplegics and may not require steroids. All of these conditions, however, mandate ophthalmologic consultation and follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree