Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

Airway management can significantly affect outcomes for hospitalized critically ill patients. Failure to deliver adequate oxygen may cause irreversible brain damage or preclude successful resuscitation. Options for management may range from assisted ventilation with a bag-valve-mask (BVM) to noninvasive ventilation (NIV) support to endotracheal intubation. A successful outcome in any intubation demands proficiency in patient assessment, knowledge of the equipment (basic and advanced), requisite technical skills, appreciation of individual limitations, and an alternative plan to deal with the difficult or failed airway.

In 2006 the Society for Hospital Medicine published the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, which listed endotracheal intubation as one of the procedural competencies for hospitalists. However, a small survey published in 2010 noted that individual hospitalists (n = 175) performed on average only 10 endotracheal intubations in the previous year with a range of 3 to 20. This limited clinical experience with advanced airway management highlights the importance of a valuable educational program for the hospitalists as well as clinicians’ understanding of their own practice and skill limitations. Depending on their clinical environment and work setting, the expectations for different hospitalists in advanced airway management will vary. However, all hospitalists should be versed in initial airway management and stabilization, including effective use of oral and nasal airway and BVM devices.

Pathophysiology

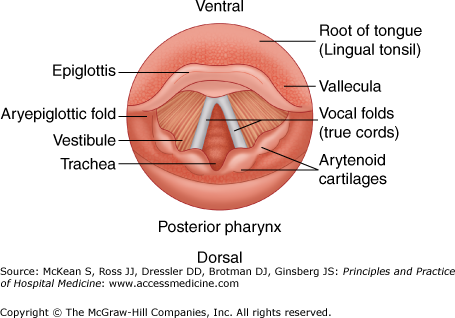

Successful intubation requires knowledge of basic airway anatomy landmarks and locations of various airway structures relative to each other to identify the glottic opening and successfully intubate. The larynx and in particular the vocal cords lie just below the epiglottis, and proper elevation of the epiglottis should allow the clinician to visualize the arytenoids and the vocal cords prior to insertion of the endotracheal tube (ETT) (Figure 122-1).

A difficult airway refers to complex or challenging BVM or endotracheal intubation. Difficult oxygenation is the inability to maintain the oxygen saturation > 90% despite using a BVM and 100% oxygen. A failed airway refers to the inability to either ventilate or intubate a patient after three intubation attempts by the same operator using multiple blades. Experienced operators uncommonly encounter this problem. Difficult ventilation occurs in 1 in 50 anesthesia cases. In one study of emergency department cases 2.7% were deemed failed intubation attempts due to unsuccessful first attempts requiring rescue techniques. A higher rate of poor clinical outcomes occurs when the airway is managed as an emergent (rather than elective) procedure. In addition, an increased number of airway attempts predicts poorer outcomes; thus a backup plan is necessary if initial intubation attempts are not successfully executed. Medical diagnoses that increase the likelihood of difficult airways range from congenital conditions that typically affect the airway anatomy to acquired conditions such as trauma, tumors, edema, infections, arthritis, and obesity. All affect the ability to adequately visualize the larynx during the intubation attempt (Table 122-1).

| Congenital |

| |

| Acquired | Infectious |

|

| Arthritis |

| |

| Tumors (benign and malignant) |

| |

| ||

| Trauma |

| |

| Obesity | ||

| Acromegaly | ||

| Inflammation |

| |

| Other |

|

Patients with large incisors, reduced distance between incisors, and reduced thyromental distance are more likely to have a poor laryngoscopic view and potentially more difficulty with intubation. Rapid assessment of these factors when one is first evaluating the patient can provide key data in development of an airway management plan. When presented with a patient that has one or more risk factors for difficult airway, additional equipment and/or personnel should be brought to the patient to assist with the airway management.

Many clinical assessment tools have been developed to predict a difficult airway, but insufficient evidence supports recommending any individual tool. The LEMON rule is one popular rule for assessment for difficult intubation (Table 122-2).

| Look | Injury, large incisors, large tongue, beard, receding mandible, obesity, abnormal face or neck pathology or shape |

| Evaluate the 3-3-2 rule | Mouth opening less than 3 fingers, mandible length less than 3 fingers, or larynx to floor of the mandible less than 2 fingers |

| Mallampati | Class III (see base of uvula) and class IV (soft palate is not visible) |

| Obstruction | Any upper airway pathology that causes an obstruction (abscess, edema, masses, epiglottitis) |

| Neck mobility | Limited mobility of neck (trauma with cervical spine immobilization arthritis) |

Operator and environmental factors may also contribute to challenges or failure to control the airway. Trainees and inexperienced clinicians (with low total numbers or infrequent intubations) may have greater difficulty intubating. When attempting to ventilate or intubate outside the controlled environment of the operating room, lack of proper patient positioning or inadequate equipment or medications may contribute to challenging intubations.

Many other factors have been associated with a difficult airway, but none accurately predicts, which patient will ultimately need more advanced techniques. Some patients who have several risk factors are intubated with ease while other patients who have no high-risk predictors on rare occasions have unforeseen difficulty with intubation or ventilation. In all cases the clinician should assess the potential risk for a difficult airway and always have a backup plan of action should initial attempt(s) at securing an airway prove unsuccessful.

Difficulty with BVM ventilation has been reported to occur in 5% of patients. Five independent risk factors for difficult BVM ventilation include age greater than 55 years, body mass index > 26 kg/m2, beard, lack of teeth, and history of snoring (Table 122-3, MOANS assessment). BVM ventilation can effectively maintain airway patency while an alternative plan is developed and implemented. However, patients with a high risk of failing BVM ventilation may require more rapid and definitive airway evaluation and management.

| Mask seal | Inadequate mask seal (beard, blood/emesis, facial trauma, operator small hands) |

| Obesity | BMI > 26 kg/m2 |

| Age | > 55 years |

| No teeth | No teeth (impairs BVM effectiveness) |

| Stiff ventilation | Asthma, COPD, ARDS, term pregnancy |

|

Indication for Intubation

All indications for endotracheal intubation can be classified as (1) failure to maintain a patent airway, (2) failure of oxygenation and/or ventilation, and (3) anticipation of a rapidly deteriorating clinical course (Table 122-4).

| Indication | Suggestive Signs |

|---|---|

| Failure to maintain a patent airway | Inability to phonate, inability to handle secretions, high risk of aspiration |

| Failure to oxygenate or ventilate | Unresponsiveness to noninvasive oxygenation or ventilation methods |

| Anticipate deterioration in clinical condition | Patient must be unaccompanied for testing, patient unable to maintain current work of breathing, likely further studies or surgery etc. |

The ability to maintain a patent airway preserves normal oxygenation and ventilation is essential to life. Maintenance of the airway protects against aspiration of gastric contents, which can have serious short- and long-term consequences for the patient after loss of consciousness or poisoning or during major acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

There are several ways to effectively assess the patency of the airway. Although widely used, the presence of a gag reflex is not one of those methods. The gag reflex is physiologically absent in many normal adults. Additionally, stimulation of the gag reflex in an altered or obtunded patient increases the likelihood of vomiting and, consequently, aspiration of gastric contents. The ability to phonate and/or converse is a reliable indicator of a patent airway. When the patient is unable to speak, the patient’s ability to handle secretions (ie, swallow) can be used as a surrogate to determine whether the airway is patent.

Noninvasive maneuvers such as a chin lift or jaw thrust or devices such as an oropharyngeal (oral) airway or a nasopharyngeal airway adjunct (nasal trumpet) may allow time to prepare for intubation by temporarily maintaining a patent airway.

|

When a patient’s inability to oxygenate does not respond to supplemental oxygen, endotracheal intubation is indicated. Rather than relying solely on the results of an arterial blood gas (ABG) value, the patient’s clinical appearance, including an assessment of vital signs and mentation, guides the decision to intubate. Awaiting ABG results may delay intubation, especially if the results conflict with the clinical impression.

Ventilatory failure is another indication for endotracheal intubation. Continuous pulse oximetry monitoring usually effectively determines the adequacy of oxygenation and the response to supplemental oxygen, but it does not assess ventilation. Capnography or ABG analysis can be used to determine a patient’s ability to ventilate or to track the patient’s response to noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. Results of these tests must also be interpreted cautiously and in conjunction with close observation of a patient’s clinical course.

Despite patent airway and adequate oxygenation and ventilation, some patients may still require elective intubation to avoid emergent intubation later. Common examples include airway protection in an overdose patient or massive gastrointestinal (GI) bleeder, rest from labored breathing that cannot be sustained in a patient with severe asthma or pneumonia, or to maintain airway patency compromised from angioedema or other conditions. Anticipation of deterioration relies heavily on the physician’s personal experience and judgment.

Contraindications

Contraindications to endotracheal intubation can be divided into either absolute or relative but these need to be tailored to the specific clinical situation. Absolute contraindications to intubation include total airway obstruction and total loss of facial or oropharyngeal landmarks, both necessitating a surgical airway. An anticipated difficult airway as described earlier is a relative contraindication to rapid sequence intubation (RSI), and in this situation consideration of awake intubation or use of the difficult airway adjuncts should be entertained. During cardiac or respiratory arrest, ventilation with a BVM, intubation, or both should be performed despite any contraindications.

Procedural Steps

RSI is now the predominant and preferred method in managing the emergent airway in a patient who requires sedation (ie, not the patient requiring a crash airway). RSI is defined as the simultaneous administration of a sedative and paralytic agent to assist in endotracheal intubation, usually via direct laryngoscopy. Central to the concept of RSI is the avoidance of assisted BVM ventilation to avoid insufflation of the stomach and minimize the risk of aspiration. Outcomes evidence supports RSI as a safe and effective technique for emergency airway management that maximizes the patient and physician likelihood of timely, successful airway management.

Seven steps (“7 Ps of RSI”) essential to successful rapid sequence intubation include (1) preparation, (2) preoxygenation, (3) premedication, (4) paralysis, (5) positioning, (6) placement of the ETT, and (7) postintubation care.

Preparation refers to the initial assessment of the patient’s airway and the decision to intubate. The clinician assesses the patient’s airway. Predictors of a difficult airway must be addressed, and backup airway devices (such as a laryngeal mask airway, gum elastic bougie, etc) prepared. Additionally, clinicians should prepare any monitors, medications, and oxygen sources. Preparation also requires appropriately trained staff to manage the airway and establishment of plans for the difficult or failed airway.

Preoxygenation involves applying 100% supplemental oxygen to induce nitrogen wash-out and maximize the amount of time available for direct laryngoscopy without oxygen desaturation. In a normal healthy adult, adequate preoxygenation can permit 7–9 minutes of apnea before oxygen desaturation occurs. In patients with comorbid diseases (eg, cardiac disease, underlying lung disease, pregnancy, etc), desaturation can occur more rapidly.

Premedication involves administration of drugs 3–5 minutes before induction and paralysis to blunt the effects of direct laryngoscopy, including bronchospasm and a strong sympathetic response. Options for pretreatment include fentanyl (3 μg/kg) administration in patients who are severely hypertensive, have underlying coronary disease, or intracranial hemorrhage if no contraindications exist. Additionally, lidocaine (1.5 mg/kg) may be administered in patients with asthma or elevated intracranial pressure. Premedication with lidocaine, however, may be labor intensive, adds time, and has little proven benefit. Care should be taken when considering any premedication due to the added complexity, adverse affects of the premedication agents, and limited proven benefit.

Paralysis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree