Key Clinical Questions

Does the hospitalized patient with unexplained dyspnea have interstitial lung disease (ILD)?

How and why should idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) be differentiated from other forms of ILD?

What is an acute exacerbation of IPF, and how can it be discriminated from other causes of worsening in ILD?

When is bronchoscopy indicated in the diagnosis or evaluation of ILD?

When should a pulmonary consultation be requested for patients with ILD?

How can patients with high oxygen requirements be transitioned home?

Introduction: Classification of Interstitial Lung Disease

The interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a heterogeneous group of disorders with the common feature of inflammatory or fibrotic injury to the lung parenchyma. Hence, these disorders are also described as the diffuse parenchymal lung diseases (DPLDs). There are numerous potential etiologies for ILD which can be broadly divided into five categories: idiopathic, drug/medication related, environmental/occupational, genetic/hereditary, and autoimmune associated (Table 241-1).

|

|

While considered rare, these diseases affect approximately 500,000 individuals in the United States each year and result in 40,000 deaths, comparable to the number of deaths from breast cancer. The exact epidemiology is difficult to determine as patients presenting with these diseases are sometimes misidentified as having more common disorders such as congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Further the epidemiology varies based on the subtype of ILD. Thus, epidemiology is best considered in the context of the ILD subsets.

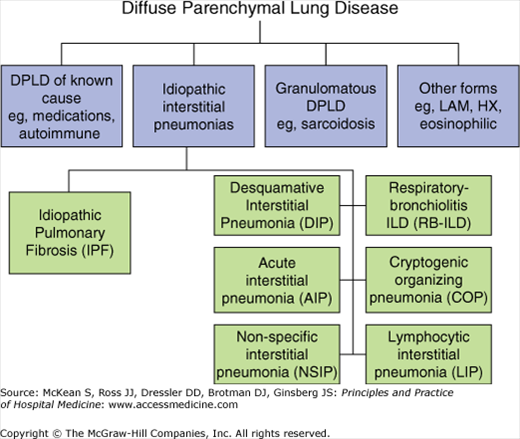

Because of the diversity of diseases encompassed in ILD, the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society developed a two-level classification system to facilitate the clinical evaluation of ILD (Figure 241-1). This system divides ILDs initially based on specific mechanisms of disease into disorders of known etiology, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, granulomatous disease, and rare diseases. The idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) are further classified in a second level based on histologic appearance. For the purpose of this discussion, we will focus primarily on the IIPs and mention several other ILDs of particular relevance to the hospitalist.

Figure 241-1

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification of interstitial lung disease. DPLD, diffuse parenchymal lung disease; LAM, lymphangioleiomyomatosis; HX, histiocytosis X. (Adapted from American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society [ATS], and the European Respiratory Society [ERS] was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165[2]:277–304.)

A 75-year-old man with a history of hypertension and coronary artery disease presents with progressive dyspnea for 3 weeks following an apparent upper respiratory infection. He has had a history of worsening dyspnea over the past year with a recent negative stress test. He was told 5 years earlier that a chest x-ray done as part of a routine physical showed scarring at the lung bases. Medications include aspirin and a beta-blocker. |

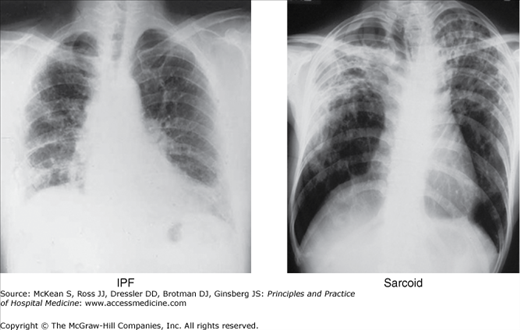

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is one of the most common ILDs encountered by hospitalists. This disorder primarily affects individuals over age 60 years. Recent epidemiologic studies show the prevalence increases with each successive decade from 18.7 to 23.3/100,000 in 55 to 64 year olds to 29.3 to 50.0/100,000 in 65 to 74 year olds to 48.4 to 87.9/100,000 in > 85 year olds. IPF affects approximately 200,000 people in the United States and results in 20,000 deaths per year. A notable exception to the older age of onset is in patients with familial IPF. In this genetic disorder, patients may present two to three decades earlier with symptomatic disease. The median survival is 3 to 5 years from the time of diagnosis in symptomatic patients. Diagnosis is made based on a consistent history (slowly progressive dyspnea), findings of dry, Velcro-like crackles on exam and consistent radiograph with basilar predominant interstitial changes (Figure 241-2). The hallmarks of IPF on chest CT are basilar predominant subpleural reticulation and honeycombing with traction bronchiectasis (Figure 241-3). Ground glass opacities may be seen during acute exacerbations, however, this should be a minor feature of a baseline CT study. The diagnosis of IPF mandates the exclusion of other etiologies including environmental exposures, medication and autoimmune disease.

Figure 241-2

Representative chest x-rays that can be seen in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and sarcoid. IPF is characterized by basilar predominant interstitial markings. By contrast, sarcoid typically shows an upper lobe distribution of fibrosis which may also be accompanied by bilateral hilar adenopathy.

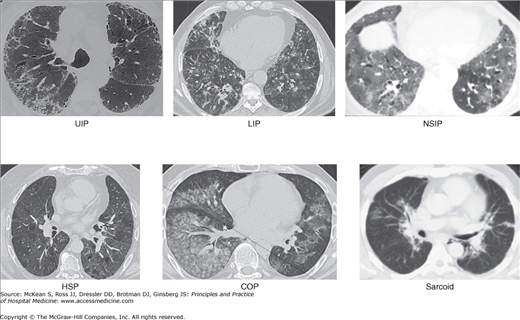

Figure 241-3

Representative computed tomography patterns that can be seen in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD). ILD can be characterized by many different radiographic patterns. With the exception of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) radiograph, there is substantial overlap among different forms of ILD. A number of the patterns are shown with the associated pathology noted. (A) UIP is characterized honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, and increased reticular markings. (B) Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia may demonstrate a micronodular pattern. (C) Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) often appears as a diffuse ground glass opacities (GGOs). (D) Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HSP) appears as a nearly homogeneous pattern of GGO. (E) Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) appears as a patchy infiltrate which may be GGO or dense. (F) Sarcoid can present with bronchovascular infiltrates and hilar adenopathy.

A 42-year-old woman presents with rapidly progressive dyspnea over 2 to 3 weeks. She has a history of Raynaud disease for several years, but recently noted onset of redness and cracking at the tips of her fingers. She has also noted a purplish rash above her eyes. In the past 4 weeks, she has had increasing difficulty rising from a chair and now is unable to get up without using her hands to push off. Her mother has a history of rheumatoid arthritis. |

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is the form of ILD most common in patients with autoimmune disease. As a result, this form of ILD is more common in women than men and has an earlier age of onset than typical with IPF. The diagnosis is typically suspected based on the clinical symptoms and radiograph showing patchy ground glass opacities with minimal fibrosis (Figure 241-3). Open lung biopsy is necessary for definitive diagnosis. The prognosis of NSIP is generally good, with the exception of patients with evidence of fibrosis.

A 37-year-old man presents with insidious onset dyspnea and cough worsening over several months. He has no prior medical history or significant exposures. He smokes one pack a day of cigarettes and has done so for 10 years. A CT on presentation shows bilateral upper lobe ground glass opacities. Work up for autoimmune disease is negative. |

Respiratory-bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) and desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP) represent a poorly appreciated spectrum of smoking-related lung disease. These disorders can occur in cigarette smokers years after starting smoking. Unlike the more commonly encountered smoking related disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and emphysema, RB-ILD and DIP are largely reversible with abstention from smoking. The age of onset of this disorder is variable, but tends to be younger than IPF. It occurs most frequently in smokers, but can be encountered occasionally in nonsmokers. The diagnosis should be suspected based on clinical presentation. However, definitive diagnosis requires lung biopsy. Complete smoking cessation can reverse most cases of RB-ILD/DIP. Individuals who develop this disorder without apparent tobacco smoke exposure can be treated with steroids, but the response is variable.

A 50-year-old woman presents with recurrent fever, cough, and dyspnea. She had similar symptoms approximately 1 month previously and received a course of oral antibiotics with some improvement, although she did not return to her baseline. Her past medical history is notable for psoriasis. She began monthly TNF-inhibitor 3 months earlier for treatment of her psoriasis. She has no other significant exposures. Her CT chest shows patchy ground glass opacities in both lungs. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree