INJURIES AND ILLNESSES DUE TO HEAT

HEAT ILLNESS (HYPERTHERMIA)

Conduction—heat exchange between two surfaces in direct contact. Lying uninsulated on hot (or cold) ground can result in significant heat exchange. The same is true for immersion into hot or cold water.

Convection—heat transferred from a surface to a gas or liquid, commonly air or water. When air temperature exceeds skin temperature, heat is gained by the body. Loose-fitting clothing allows air movement and assists conductive heat loss.

Radiation—heat transfer between the body and the environment by electromagnetic waves. Clothing protects the body from radiant heat, and the skin radiates heat away from the body. Highly pigmented skin absorbs more heat than nonpigmented skin.

Evaporation—consumption of heat energy as liquid is converted to a gas. Evaporation of sweat is an effective cooling mechanism.

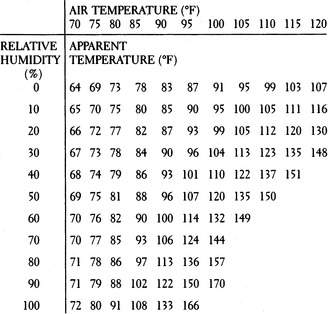

In the normal situation, the skin is the largest heat-wasting organ, and radiates approximately 65% of the daily heat loss. The skin is also largely responsible for evaporation (of sweat). Extreme humidity impedes evaporation and greatly diminishes human temperature control. The National Weather Service heat index (Figure 178) roughly correlates air temperature and relative humidity to derive an “apparent temperature.” At all temperatures, humidity makes the situation worse. For instance, at an air temperature of 85°F, if the relative humidity is 80%, the apparent temperature is 97°F.

To summarize these recommendations:

| Apparent Temperature Range | Dangers/Precautions at This Range |

|---|---|

| 80°F–90°F (27°C–32°C) | Exercise can be difficult; enforce rest and hydration |

| 90°F–105°F (32°C–41°C) | Heat cramps and exhaustion; be extremely cautious |

| 105°F–130°F (41°C–54°C) | Anticipate heat exhaustion; strictly limit activities |

| 130°F and above (54°C and above) | Setting for heatstroke; seek cool shelter |

When maximally effective, the complete evaporation of 1 quart (liter) of sweat from the skin removes 600 kilocalories of heat (equivalent to the total heat produced with strenuous exercise in 1 hour). Sweat that drips from the skin without evaporating does not contribute to the cooling process, but may contribute to dehydration. World-class distance runners who are acclimated to the heat can sweat in excess of 3½ quarts per hour. Since the maximum rate of gastric emptying (a surrogate for fluid absorption) is only 1.2 quarts per hour, it is easy to see how a person can become dehydrated. Thus, a person should be able to tolerate a 1 quart per hour sweat rate and manage rehydration with oral fluids. The scalp, face, and torso are most important in terms of sweating.

HEAT EXHAUSTION AND HEATSTROKE

The signs and symptoms of heatstroke are extreme confusion, weakness, dizziness, unconsciousness, low blood pressure or shock (see page 60), seizures, increased bleeding (bruising, vomiting blood, bloody urine), diarrhea, vomiting, shortness of breath, red skin rash (particularly over the chest, abdomen, and back), darkened (“machine oil”) urine, and major core body temperature elevation (up to 115.7°F, or 46.5°C, has been reported in a heatstroke survivor). Again, it is important to note that sweating may be present or absent. At the time of collapse, most victims of heatstroke are still sweating copiously. It is rare for someone to feel cool externally when his temperature exceeds 105°F (45°C), but it is not impossible.

The most important aspect of therapy is to lower the temperature as quickly as possible. The body may lose its ability to control its own temperature at 106°F (41.1°C), so from that point upward, temperature can skyrocket. Manage the airway (see page 22) and administer oxygen (see page 431) at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute by facemask. Do not give liquids by mouth unless the victim is awake and capable of purposeful swallowing. Cooled liquids do not assist the cooling process enough to risk choking the uncooperative or confused victim.

Cooling the Victim

1. Remove the victim from obvious sources of heat. Shield him from direct sunlight and remove his clothing. Stop him from exercising.

2. The most efficient method of cooling is to drench the victim with large quantities of crushed ice and water, accompanied by vigorous massage. If you have a limited amount of ice, place ice packs in the armpits, behind the neck, and in the groin. There are safety issues to consider with total body immersion in cold water to treat hyperthermia, including access to the victim and even the risk for near-drowning. However, in a life-threatening field situation, if the only method available for cooling is immersion in a cold mountain stream, do it! Be alert for the need to remove the victim from the water to accomplish resuscitative measures (e.g., cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR]). Never leave the victim unattended.

3. If ice is not available, wet down the victim and begin to fan him vigorously. Evaporation is a very efficient method of heat removal. Use cool or tepid water; do not sponge the victim with alcohol. If electric fans are available, use them. Do not be concerned with shivering, so long as you continue to aggressively cool the victim.

4. There is a device on the market (CORECONTROL) for athletes that increases circulation through the hand to allow a cooling mechanism to have its effect on this area of brisk heat transfer.

5. Recheck the temperature every 5 to 10 minutes, to avoid cooling much below 98.6°F (37°C). When you have cooled the victim to 99.5°F to 100°F (37.5°C to 37.8°C), taper the cooling effort. After the victim is cooled, recheck his temperature every 30 minutes for 3 to 4 hours, because there will often be a rebound temperature rise.

6. Do not use aspirin or acetaminophen unless the victim has an infection. These specific drugs are used to combat fever that is caused by the release of chemical compounds from infectious agents into the bloodstream. Such compounds affect the portion of the brain (hypothalamus) that serves as the body’s thermostat, causing body temperature to rise. Aspirin or acetaminophen acts to block this chemical interaction in the brain, and thus eliminates the fever. If elevated body temperature is not caused by an infection, aspirin or acetaminophen will not work—and may in fact be harmful, leading to bleeding disorders or liver inflammation, respectively.

7. If the victim is alert, begin to correct dehydration (see page 208) using oral rehydration. Be certain that the concentration of carbohydrates or sugar in the beverage does not exceed 6%, so as not to inhibit intestinal absorption. Try to get 1 to 2 quarts (liters) into the victim over the first few hours. For every pound (0.45 kg) of weight loss attributed to sweating, have the victim ingest a pint (473 mL or 2 cups) of fluid. This may take up to 36 hours.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree