INJURIES AND ILLNESSES DUE TO COLD

HYPOTHERMIA (LOWERED BODY TEMPERATURE)

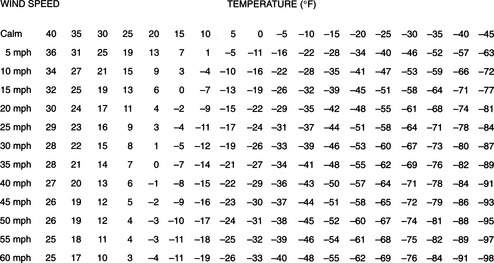

Heat is lost from the body to the environment by direct contact (conduction), air movement (convection), infrared energy emission (radiation), the conversion of liquid (sweat) to a gas (evaporation), and the exhalation of heated air from the lungs (respiration). It is important to note that the rate of heat loss via conduction is increased 5-fold in wet clothes and at least 25-fold in cold-water immersion. Windchill (Figure 176) refers to the increase in the rate of heat loss (convection) that would occur when a victim is exposed to moving air. This chill can be compounded further if the victim is wet (conduction, convection, and evaporation).

Immersion hypothermia refers to the particular case in which a victim has become hypothermic because of sudden immersion into cold water. Again, water has a thermal conductivity approximately 25 times greater than air, and a person immersed in cold water rapidly transfers heat from his skin into the water. The actual rate of core temperature drop in a human is determined in part by these phenomena and in part by how quickly heat is transferred from the core to the skin, skin thickness, the presence or absence of clothing, the initial core temperature, gender, fitness, water temperature, drug effects, nutritional status, and behavior in the water.

A sudden plunge into cold water causes the victim to hyperventilate (see page 300), which may lead to confusion, muscle spasm, and loss of consciousness. The cold water rapidly cools muscles and the victim loses the ability to swim or tread water. Muscles and nerves may become ineffective within 10 minutes. Over the ensuing hour, shivering occurs and then ceases. Anyone pulled from cold water should be presumed to be hypothermic. In terms of survival, the aphorism is that when a person is plunged into very cold water (32°F or 0°C), he or she has 1 minute to control breathing (e.g., to stop hyperventilating from the “gasp reflex”), 10 minutes of purposeful movement before the muscles are numb and not responsive, 1 hour before hypothermia leads to unconsciousness, and 2 hours until profound hypothermia causes death.

91.4°F to 98.6°F (33°C to 37°C). Sensation of cold; shivering; increased heart rate; urge to urinate; slight incoordination in hand movements; increased respiratory rate; increased reflexes (leg jerk when the knee is tapped); red face; muscular incoordination, stumbling gait, maladaptive behavior, rapid heart rate converting to slow heart rate, apathy.

85.2°F to 91.4°F (29°C to 33°C). Stupor; decreased or absent shivering; weakness; apathy, drowsiness, and/or confusion; poor judgment; slurred speech; inability to walk or follow commands; paradoxical undressing (inappropriate behavior); complaints of loss of vision; amnesia; rapid heart rate converting to slow heart rate; rapid breathing rate converting to shallow breathing; loss of shivering; possible nonreactive or dilated pupils, abnormal heart rhythms, diminished breathing.

71.6°F to 85.2°F (22°C to 29°C). Minimal breathing; coma; decreased respiratory rate; decreased neurologic reflexes progressing to no reflexes; no voluntary motion or response to pain; very slow heart rate, low blood pressure; maximum risk for ventricular fibrillation. The victim no longer can control his body temperature and rapidly cools to the surrounding environmental temperature.

Below 71.6°F (22°C). Rigid muscles; barely detectable or absent blood pressure, heart rate, and respirations; dilated pupils; risk for ventricular fibrillation; appearance of death.

Unless the victim has suffered a full cardiopulmonary arrest, the hypothermia itself may not be harmful. Unless tissue is actually frozen, cold is in many ways protective to the brain and heart. However, if a hypothermic victim is improperly transported or rewarmed, the process may precipitate ventricular fibrillation, in which the heart does not contract, but quivers in such a fashion as to be unable to pump blood. The burden of rescue is to transport and rewarm the victim in a way that does not precipitate ventricular fibrillation.

The following general rules of therapy apply to all cases:

1. Handle all victims gently. Rough handling can cause the heart to fibrillate (cause a cardiac arrest). Secure the scene and avoid creating additional victims via unstable snow, ice, or rock fall.

2. If necessary, protect the airway (see page 22) and cervical spine (see page 37). Stabilize all other major injuries, such as broken bones.

3. Prevent the victim from becoming any colder. Provide a shelter. Remove all his wet clothing and replace it with dry clothing. Don’t give away all of your clothing, however, or you may become hypothermic. Replace wet clothing with sleeping bags, insulated pads, bubble wrap, blankets, or even newspaper. The “blizzard pack” from Blizzard Protection Systems, Ltd. (www.blizzardpack.com) can be used to provide protection from the elements. The Pro-Tech Extreme bag or vest, SPACE brand emergency bag, SPACE brand all-weather blanket, and SPACE brand emergency blanket, all from MPI Outdoors (www.mpioutdoors.com), are other options for this purpose.

4. Do not attempt to warm the victim by vigorous exercise, rubbing the arms and legs, or immersing in warm water. This is “rough handling” and can cause the heart to fibrillate if the victim is severely hypothermic.

Mild Hypothermia

Prevent the victim from becoming any colder. Get him out of the wind and into a shelter. If necessary, build a fire or ignite a stove for added warmth. Gently remove wet items of clothing and replace them with dry garments. This is very important, even if the victim will be very briefly exposed out in the open. If no dry replacements are available, the clothed victim should be covered with a waterproof tarp or poncho to prevent evaporative heat loss. Cover the head, neck, hands, and feet. Insulate the victim above and below with blankets. If the victim is coherent and can swallow without difficulty, encourage the ingestion of warm sweetened fluids. Good choices include warm gelatin (Jell-O), juice, or cocoa, because carbohydrates fuel shivering. If only cool or cold liquids are available for drinking, this is fine. Avoid heavily caffeinated beverages. If a dry sleeping bag is available, one or more rescuers should climb in with the victim and share body heat. However, this technique may not be very effective, and great care must be taken not to cause the victim to become wet (e.g., from the rescuer’s sweat). Do not apply commercial heat packs, hot-water-filled canteens, or hot rocks directly to the skin; they must be wrapped in blankets or towels to avoid serious burns. Try to keep the victim in a horizontal position until he is well hydrated. Do not vigorously massage the arms and legs, because skin rubbing suppresses shivering, dilates the skin, and does not contribute to rewarming.

Severe Hypothermia

Examine the victim carefully and gently for signs of life. Listen closely near the nose and mouth and examine chest movement for spontaneous breathing. Feel at the groin (femoral artery) and neck (carotid artery) for a weak and/or slow pulse (see page 33).

If the victim shows any signs of life (movement, pulse, respirations), do not initiate the chest compressions of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). If the victim is breathing regularly, even at a subnormal rate, his heart is beating. Because hypothermia is protective, the victim does not require a “normal” heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. Pumping on the chest unnecessarily is “rough handling,” and may induce ventricular fibrillation. Administer supplemental oxygen (see page 431) by facemask if it is available.

If the victim is breathing at a rate of less than 6 to 7 breaths per minute, you should begin mouth-to-mouth breathing (see page 29) to achieve an overall rate of 12 to 13 breaths per minute.

If help is on the way (within 2 hours) and there are no signs of life whatsoever, or if you are in doubt (about whether the victim is hypothermic, for instance), you should begin standard CPR (see page 32). If possible, continue CPR until the victim reaches the hospital. Rescue breathing should take priority over chest compressions, particularly in the victim of cold-water immersion. There have been documented cases of “miraculous” recoveries from complete cardiopulmonary arrest associated with environmental hypothermia after prolonged resuscitation, presumably because of the protective effect of the cold. Remember, “no one is dead until he is warm and dead.” However, all of these victims were ultimately resurrected in the hospital, after they had been fully rewarmed.

Preparing a Hypothermic Victim for Transport

1. Keep the victim dry. Replace all wet clothing. If there is no replacement clothing available, wring out the wet clothing, including gloves and mittens, and then put it back on the victim. Lay the victim on a sleeping bag and then cover him with a layer of blankets. If necessary, use bubble wrap or some other insulating material. If the hands are extremely cold, pull them out of the sleeves of clothing in order to put the hands in the victim’s armpits for warming. See above for emergency waterproof blankets and bags. Cover everything with a plastic sheet.

2. Keep the victim horizontal. Do not allow massage of the extremities. Do not allow the victim to exert himself.

3. Splint and bandage all injuries as appropriate. Cover all open wounds.

4. Limit rewarming to methods that prevent further heat loss. Place insulated (e.g., with clothing) hot-water bottles in the victim’s armpits and groin. Keep his head and neck covered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree