Influence of Female Hormones on Migraines

Hélène Massiou

E. Anne MacGregor

IHS AND WHO CODE NUMBERS

8.3.1 [G44.418] Exogenous hormone-induced headache

8.4.3 [G44.83] Estrogen-withdrawal headache

A1.1.1 Pure menstrual migraine without aura

A1.1.2 Menstrually-related migraine without aura

The evidence is plentiful for a link between female hormones and migraine. The female preponderance of migraine appears after puberty; in many patients, migraine occurs at the time of menses and improves during pregnancy; hormonal treatments may modify the course of the migrainous disease. Studies suggest that the lifetime prevalence of migraine in women is as great as 25%, compared with only 8% of men (1).

GENETICS

Estrogens play a major role in migraine in women, but there is a large variability in their effect, which might be explained by the intrinsic estrogen-receptor sensitivity of the hypothalamic neurons. Limited data suggest that this may have a genetic basis (2).

MENARCHE AND MIGRAINE

The female: male ratio of migraine is around 1:1 during childhood, with even a small preponderance in boys. This trend is completely reversed after puberty, and the female: male incidence ratio in adults reaches 2:1 to 4:1. Several studies show female preponderance in childhood for migraine with aura, but not for migraine without aura (3,4); this difference, however, was not observed by other researchers (5). At puberty, the incidence of migraine without aura rises in girls (6), with 10 to 20% of women reporting migraine with menarche (7).

MENSTRUAL MIGRAINE

More than 50% of women with migraine, both in the general population and presenting to specialist clinics, report an association between migraine and menstruation (8,9).

8.3.1 Exogenous Hormone-Induced Headache

Diagnostic Criteria

Headache or migraine fulfilling criteria C and D

Regular use of exogenous hormones

Headache or migraine develops or markedly worsens within 3 months of commencing exogenous hormones

Headache or migraine resolves or reverts to its previous pattern within 3 months after total discontinuation of exogenous hormones

8.4.3 Estrogen-Withdrawal Headache

Diagnostic Criteria

Headache or migraine fulfilling criteria C and D

Daily use of exogenous estrogen for at least 3 weeks, which is interrupted

Headache or migraine develops within 5 days after last use of estrogen

Headache or migraine resolves within 3 days

A1.1.1 Pure Menstrual Migraine Without Aura

Diagnostic Criteria

Attacks, in a menstruating woman, fulfilling criteria for 1.1 Migraine without aura

Notes

1. The first day of menstruation is day 1 and the preceding day is day −1; there is no day 0.

2. For the purposes of this classification, menstruation is considered to be endometrial bleeding resulting from either the normal menstrual cycle or from the withdrawal of exogenous progestogens, as in the case of combined oral contraceptives and cyclical hormone replacement therapy.

A1.1.2 Menstrually-Related Migraine Without Aura

Diagnostic Criteria

Attacks, in a menstruating woman, fulfilling criteria for 1.1 Migraine without aura

Attacks occur on day 1 ± 2 (i.e., days −2 to +3) (a) of menstruation (b) in at least two out of three menstrual cycles and additionally at other times of the cycle

Notes

1. The first day of menstruation is day 1 and the preceding day is day −1; there is no day 0.

2. For the purposes of this classification, menstruation is considered to be endometrial bleeding resulting from either the normal menstrual cycle or from the withdrawal of exogenous progestogens, as in the case of combined oral contraceptives and cyclical hormone replacement therapy.

Definition

The International Classification of Headache Disorders includes specific definitions for pure menstrual migraine and menstrually related migraine (10). These were based on studies that showed that migraine is most likely to occur on or between 2 days before menstruation and the first 3 days of bleeding (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

Epidemiology and Clinical Aspects

The prevalence figures of menstrual migraine depend on its definition, as well as on the method of recording data. Studies based on patients’ self-assessment usually lead to an overestimation. In studies using prospective diary cards, the percentage of migraineurs who suffer from menstrual migraine associated with other attacks during the cycle ranges from 24 to 56% (3,4). Only 7% of the migraineurs suffer from pure menstrual migraine (13). In some women, attacks occur at each menstruation, whereas in others they are inconstant, occurring only in some cycles. Migraine without aura but not migraine with aura shows a strong association with menstruation (4,14). Menstrual migraine without aura is more frequent in women whose onset of this type of migraine takes place at menarche (4). An association between menstrual migraine and the premenstrual syndrome (PMS) was found in two studies, but requires confirmation because patients samples were small (17,18). In several studies, menstrual attacks were found to be more severe, of longer duration, and more resistant to therapy than other attacks (9,16,19). In one survey, however, few significant differences were observed between menstrual and nonmenstrual attacks, with only pain intensity being greater for attacks during the first 2 days on menses (15).

Pathophysiology

Estrogen and progesterone are the main hormones that have been investigated in relation to migraine but studies comparing levels of these hormones in women with menstrual migraine versus controls have not found any convincing differences. It also seems that ovulation is not necessary to provoke menstrual attacks because women with migraine using combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC), inhibiting ovulation, still experience migraine occurring during the hormone-free interval. Research has therefore focused on the naturally declining levels of estrogen and progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.

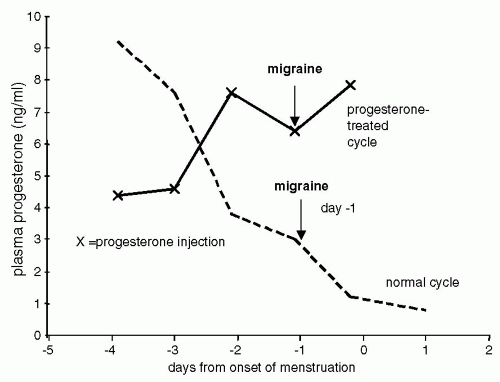

Progesterone

Estrogen

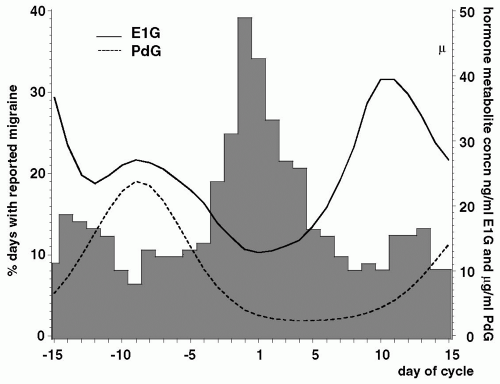

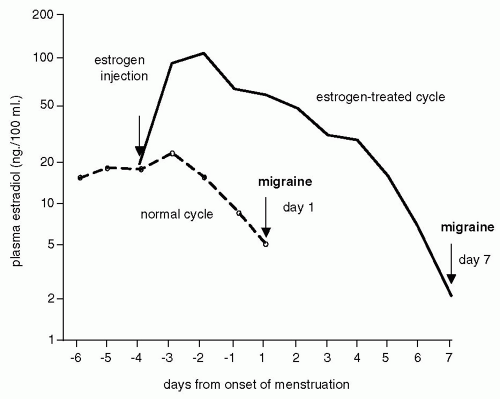

There is evidence that menstrual attacks of migraine are associated, at least in some women, with falling levels or withdrawal of estrogen (24, 25, 26, 27). Somerville noted that a period of estrogen priming with several days of exposure to high estrogen levels is necessary for migraine to result from estrogen withdrawal, as occurs in the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle (28, 29, 30). This explains why migraine is not associated with ovulation. MacGregor et al. noted that migraine was inversely associated with urinary estrogen levels across the menstrual cycle: attacks were significantly more likely to occur in association with falling estrogen in the late luteal/early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and less likely to occur during the subsequent part of the follicular phase during which estrogen levels rose (22) (Fig. 35-2). If estrogen withdrawal is a trigger for migraine, averting the drop in estrogen using estrogen supplements should prevent attacks. Trials using estrogen supplements, usually started 48 hours before the earliest expected onset of menstrual attacks, confirm the efficacy of this approach (31, 32, 33). However, in some cases, treatment may only defer migraine until later in the cycle (28,31) (Fig. 35-3).

FIGURE 35-1. The role of progesterone in menstrual migraine. Based on Somerville (23). |

FIGURE 35-2. Incidence of migraine, urinary estrone-3-glucuronide (E1G) and pregnanediol-3-glucuronide (PdG) levels on each day of the menstrual cycle in 120 cycles from 38 women. |

FIGURE 35-3. The role of estradiol withdrawal in menstrual migraine. Based on Somerville (28). |

Other Mechanisms

It is likely that menstrual cycle hormone changes trigger some alteration in activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, exposing susceptible women to a migraine attack. For example, estrogens are neurosteroids, known to raise levels of endorphins (34); aberrant opioid control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis has been reported in menstrual migraine (35). Close interrelationships between estrogens and other brain neurotransmitters have also been confirmed, especially the catecholamines, noradrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine (36). Fluctuating estrogen levels are associated with impaired glucose tolerance in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, which could trigger migraine (37,38). Other differences reported in menstrual migraine versus control groups include changes in aldosterone levels (39), intracellular magnesium (40), and platelet homeostasis (41).

Prostaglandins have also been implicated in menstrual migraine (42). In particular, entry of prostaglandins into the systemic circulation can trigger throbbing headache, nausea, and vomiting (43). In the uterus, prostaglandins are synthesized primarily by the endometrium. There is a threefold increase in prostaglandin levels in the uterine endometrium from the follicular to the luteal phase, with a further increase during menstruation (44). As a result of the withdrawal of estrogen and progesterone, the endometrium breaks down and prostaglandins are released. This causes vasoconstriction within the endometrium and disruption of endometrial cells, stimulating further prostaglandin synthesis. When an excessive amount of prostaglandins gains entrance to the circulation, other systemic symptoms occur that are characteristically associated with menorrhagia and/or dysmenorrhea such as headache and nausea (45,46). Plasma taken premenstrually from women with dysmenorrhea and then reinfused postmenstruation into the same women resulted in premenstrual symptoms, including headache (47). Therefore, prostaglandins may have a specific role in migraine associated with dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia. In support of this, prostaglandin inhibitors are effective for the prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine (48).

Some postmenopausal women, not taking hormonal treatments, continue to have regular monthly migraine attacks. Migraine attacks can also be cyclical in men, suggesting that some central phenomenon is responsible for these cycles (49).

DIAGNOSIS

Diary cards kept prospectively over a minimum of three cycles are necessary to confirm the relationship between migraine and menstruation; many women already keep a note of this in their personal diaries. Relying on the history to make the diagnosis of menstrual migraine is not recommended.

Investigations

Many women expect some sort of investigation to be undertaken, either a test of their hormones or a brain scan. However, there is no place for specific investigations in clinical practice, other than those indicated to exclude suspected secondary headache resulting from underlying pathology.

MANAGEMENT

For the majority of women, reporting menstrual attacks management does not differ from standard treatment recommendations. Initial strategies should include acute medication and the provision of diary cards. Effective acute treatment is usually all that is necessary, particularly if attacks only occur once or twice a month.

SYMPTOMATIC TREATMENT

The treatment of menstrual attacks of migraine is the same as for nonmenstrual attacks. Acute treatment regimens usually include analgesics with or without prokinetic antiemetics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), triptans, and ergot derivatives. Most triptans have been shown to be effective for migraine attacks with menstruation (50, 51, 52, 53, 54). However, within-woman analyses of menstrual versus nonmenstrual attacks are awaited.

Identification of Nonhormonal Triggers

Assuming the concept of multiple factors acting in combination to trigger migraine, hormonal factors combine with nonhormonal triggers to increase the overall susceptibility to attacks at the time of menstruation (55). Therefore, every effort should be made to identify and eliminate nonhormonal triggers around the time of menstruation.

Diary Cards

By the time the diary cards are reviewed at follow-up, a percentage of patients have their attacks under control, with no need for further intervention. Another group have attacks throughout the cycle; these women may benefit from standard prophylactic therapy, if considered necessary.

Specific Prophylaxis for Menstrual Migraine

Only a small percentage of women have menstrual migraine and wish to consider specific prophylaxis. Nonpharmacologic prophylaxis of menstrual migraine appears to be ineffective (56,57). None of the drugs and hormones recommended below are licensed for management of menstrual migraine because, although effective in clinical trials, evidence is limited. Given that there are no investigations to identify the most effective prophylactic, an empirical approach is necessary, prescribing on a “named” patient basis. Because of the fluctuating nature of migraine, it is sensible to try a method for at least two to three cycles before considering alternative prophylaxis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree