Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a relatively common infection in the hospital setting, with an inpatient mortality rate of about 18%. The incidence of IE rises linearly with age, from around 1 case per 100,000 person-years among young adults, to over 10 cases per 100,000 person-years among those older than 75 years. The hallmark lesion of IE is the endocardial vegetation. Although the heart valves are affected most commonly, IE also may involve septal defects, mural endocardium, or prosthetic cardiac structures. Vegetations may result in valvular regurgitation or obstruction, myocardial abscess, or mycotic aneurysm. Definitive diagnosis requires identification of the causative organism in blood, cardiac structures, or emboli. Cure requires prolonged antimicrobial treatment and often valve replacement surgery, leading to substantial expense.

Epidemiology

Historically, IE was a disease of younger patients with rheumatic heart disease, and mainly involved viridans group streptococci. Over the last decade, however, a new form of the disease, health care–associated IE, has emerged. This new form of IE is distinct in its microbiology (predominantly Staphylococcus aureus) and risk factors (eg, intravenous catheters, hyperalimentation lines, pacemakers, dialysis shunts). It represents about one-third of all IE cases among noninjection drug users with native valve disease.

Almost any type of structural heart disease may predispose to IE, especially when the defect results in turbulent blood flow. Right-sided IE is primarily an infection of injection drug users and patients with indwelling transvenous pacemakers. In developed countries, the proportion of cases related to rheumatic heart disease has declined to 5% or less in the past 2 decades, while in developing countries, rheumatic heart disease remains the most common predisposing cardiac condition. Congenital bicuspid aortic valve is the underlying lesion in more than 15% of IE cases in patients (especially men) older than 60 years, and is associated with a poor prognosis, despite rapid valve replacement. Degenerative cardiac lesions (eg, calcified mitral annulus, calcific nodular lesions secondary to arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and post–myocardial infarction thrombus) assume the greatest importance in the 30% to 40% of IE patients without any demonstrable underlying valvular disease. Marfan syndrome, when associated with aortic insufficiency, also has been associated with IE. Intravascular infections involving cardiac devices (eg, permanent cardiac pacemakers, defibrillators) also have increased significantly since the 1990s. Injection drug users are at high risk for recurrent and polymicrobial IE.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

Mitral and aortic valvular involvement are most common in IE. Distributions of valvular involvement range from 28% to 45% of cases for isolated mitral valve IE, 5% to 36% for isolated aortic valve IE, and 0% to 35% for combined aortic and mitral valves IE. In the absence of injection drug use, the tricuspid valve rarely is involved (0–6% of cases). Pulmonary valve IE is rare (< 1%) in any clinical circumstance.

Valves most commonly affected by IE (in decreasing order of frequency)

Note: mechanical and bioprosthetic valves are affected equally |

The development of IE probably requires several independent events. The normal myocardial endothelial lining is relatively resistant to infection, and constant blood flow thwarts bacteria and fungi from settling on an endocardial surface. The initiation of IE requires the simultaneous presence of both a predisposing endocardial abnormality and microorganisms in the bloodstream (bacteremia). Occasionally, massive bacteremia or particularly virulent microorganisms—especially S aureus—may cause IE on normal valves.

Bacteremia may occur whenever a mucosal surface heavily colonized with bacteria is traumatized, such as with dental extractions and invasive procedures, as well as gastrointestinal, urologic, and gynecologic procedures. The degree of bacteremia is proportional to the trauma produced by the procedure and to the number of organisms inhabiting the surface.

Many microorganisms have been identified in IE, but streptococci and staphylococci account for 80% to 90% of the cases in which an organism is isolated. The most common etiologic agents are outlined in Table 197-1.

| Percentage of Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of Endocarditis | Drug Users | Nondrug Users | Prosthetic Valve |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 68 | 28 | 23 |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus | 3 | 9 | 17 |

| Viridans group streptococci | 10 | 21 | 12 |

| Streptococcus bovis | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| Other streptococci | 2 | 7 | 5 |

| Enterococcus species | 5 | 11 | 12 |

| HACEK | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Fungi/yeast | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Polymicrobial | 3 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Negative culture findings | 5 | 9 | 12 |

| Other | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Surgical therapy | 38 | 48 | 49 |

| In-hospital mortality | 10 | 17 | 23 |

S aureus is the most common cause of native valve IE, prosthetic valve IE, and injection-drug use associated IE. It is associated with aggressive disease, extracardiac metastatic infections, and a high mortality rate. Group A, C, and G streptococci cause aggressive IE with high mortality (up to 70%). Group B streptococci also lead to acute disease with high mortality, often requiring valve replacement. It is more common in elderly or immunosuppressed patients. Streptococcus pneumoniae is no longer common, but is notable for its acute and destructive course. A classical, often lethal presentation was Austrian’s triad (simultaneous pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis, and IE). Pseudomonas aeruginosa and enteric gram-negative rods cause acute IE, and require surgery for cure. Although traditionally thought to be primarily an infection of injection drug users, recent studies have demonstrated that the primary risk factor for gram-negative IE is health care contact.

Risk factors for infective endocarditis

|

Viridans group streptococci are the most common cause of community-acquired, subacute IE. Enterococci also usually present in subacute fashion, and comprise about 10% of IE. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species are typically associated with subacute disease, accounting for 20% of IE associated with prosthetic valves, and 8% of cases of native valve IE. HACEK organisms (Haemophilus aphrophilus, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingae) cause subacute disease, causing about 5% of all IE. Fungi are uncommon pathogens in IE, but devastating when they occur. They present subacutely, with bulky, destructive, and recaltitrant vegatations, and almost always require surgery for cure.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of IE is non-specific, and the differential diagnosis is broad (Table 197-2). The diagnosis of IE may be delayed or occasionally missed entirely because of its protean manifestations. Thus, the clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion for this potentially lethal infection. Factors contributing to the overall clinical picture of IE include local cardiac complications, embolization, which may involve any organ and is clinically underappreciated, persistent bacteremia, often leading to metastatic infection, and immunopathologic factors.

| Findings | % Patients |

|---|---|

| Examination | |

| Fever (> 38°C) | 96 |

| New murmur | 48 |

| Worsening of old murmur | 20 |

| Vascular embolic event | 17 |

| Splenomegaly | 11 |

| Splinter hemorrhages | 8 |

| Conjunctival haemorrhage | 5 |

| Janeway lesions | 5 |

| Osler nodes | 3 |

| Roth spots | 2 |

| Laboratory studies | |

| Elevated C-reactive protein | 62 |

| Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 61 |

| Hematuria | 26 |

| Elevated rheumatoid factor | 5 |

Traditionally, IE was classified as acute or subacute. Acute IE is associated with S aureus, S pyogenes, or S pneumoniae. Fever is almost always present. Patients often appear toxic and occasionally exhibit septic shock. Untreated cases are rapidly fatal. Although most patients with subacute IE will develop valvular dysfunction, only half of patients with acute IE will have a detectable cardiac murmur on initial examination. In right-sided endocarditis, septic pulmonary emboli may cause cough, pleuritic chest pain, and sometimes hemoptysis.

Subacute IE (death occurring in 6 weeks to 3 months) and chronic IE (death occurring later than 3 months) often occur in the setting of prior valvular disease, with viridans streptococci as a frequent pathogen. Symptoms are vague: low-grade fever (< 39°C), night sweats, fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Chills and arthralgias may occur. Symptoms and signs of valvular insufficiency may be present. Initially, up to 15% of patients have fever or a murmur, but eventually almost all develop both.

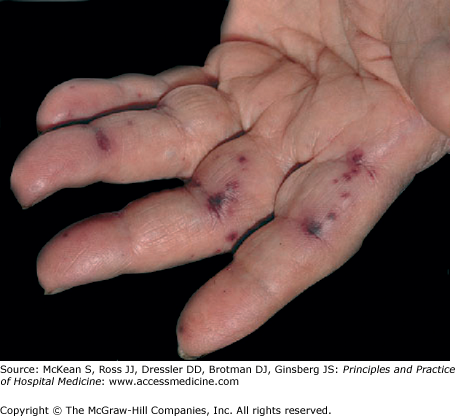

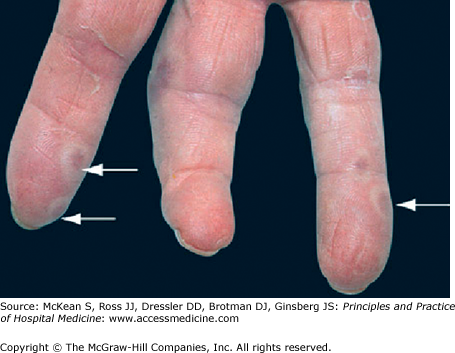

Physical examination is often entirely normal, especially in patients with a short duration of symptoms. Findings, when present, may include pallor, fever, change in a prior murmur or development of a new regurgitant murmur, and tachycardia. Retinal emboli can cause round or oval hemorrhagic retinal lesions with small white centers (Roth spots). Cutaneous manifestations include petechiae (on the upper trunk, conjunctivae, mucous membranes, and distal extremities), nontender hemorrhagic macules on the palms or soles (Janeway lesions; Figure 197-1), painful erythematous subcutaneous nodules on the tips of digits (Osler nodes; Figure 197-2), and splinter hemorrhages under the nails. Approximately one-third of IE patients have neurologic disease which may include transient ischemic attacks, stroke, toxic encephalopathy, brain abscess, or subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with mycotic aneurysm rupture. Renal emboli may cause flank pain or gross hematuria, while splenic emboli cause left upper quadrant pain. Prolonged infection may cause splenomegaly or clubbing of fingers and toes.

Figure 197-2

Osler nodes: painful nodules in the fingers and toes, now rarely observed in endocarditis. Formerly thought to be immune-complex related, but probably have a similar pathogenesis to Janeway lesions, except that the microemboli are lodged in more sensitive dermal tissue. (Reproduced, with permission, from Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. Fig. 151-11.)

This historical classification ignores the the frequent overlap in manifestations of infection by specific organisms, such as the enterococci, and the fact that most IE in the 21st century are acute infections. Therefore classification based on the etiologic causes for IE is more useful as it has implications for the expected clinical course, the likelihood of preexisting heart disease, and the appropriate antimicrobial therapy.