CHAPTER 13 INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION

INFECTION

Infection is common in the ICU and may be the primary cause of a patient’s admission, or may occur as a secondary phenomenon in patients who are already critically ill and whose normal barriers to infection are impaired. Factors that predispose to infection in critically ill patients are shown in Box 13.1. (See also Infection control, p. 19)

Box 13.1 Factors predisposing to infection in critical illness

Effects of sedative and analgesic agents (suppressed cough reflex, GI stasis, etc.)

Vascular catheters, urinary catheters and drains

Poor nutrition and impaired tissue healing

Immune suppressive effects of drugs

Increased risk of cross-infection

Prolonged broad spectrum antibiotics selecting out resistant and other organisms

SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE SYNDROME (SIRS)

It is now recognized that many processes (including infection) may trigger activation of endothelial cells, white cells, platelets and other cells, leading to the release of proinflammatory mediators, including platelet-activating factor (PAF), tumour necrosis factor (TNFα), interleukins, chemokines and other inflammatory mediators. These have effects such as increased vascular permeability (capillary leak), vasodilatation, sequestration of neutrophils, platelet adhesion and activation of complement systems. Simultaneous activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and failure of the microcirculation. Indeed, in sepsis, the coagulation and inflammatory pathways are inextricably linked and mutually activated.

DEFINITIONS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)

The systemic inflammatory response syndrome can be said to exist when two of the criteria listed in Box 13.2 are present, in the absence of a documented infection.

Sepsis

Features of SIRS, together with a documented infection. The infection may be bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic or other organism. Difficulty may sometimes arise in patients with positive cultures in distinguishing between clinically insignificant colonization and true infection (see below).

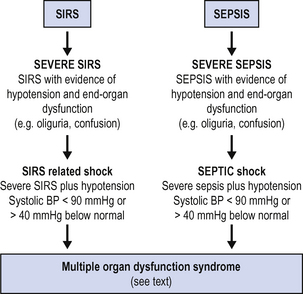

Both SIRS and sepsis may vary in severity from mild to severe, and both may progress to multiorgan dysfunction. Parallel definitions may be used, as shown in Fig. 13.1.

DISTINGUISHING INFECTION

In view of the similarities in the clinical picture produced by SIRS and sepsis (above), the problem may arise as how to distinguish infection. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a commonly used marker of infection but is not specific. Procalcitonin is an alternative marker that is thought to be more specific for infection, but is not yet widely available.

antigen tests, antibody titres, e.g. diagnosis of fungal infection esp. Candida, Aspergillus (24–48 h).

antigen tests, antibody titres, e.g. diagnosis of fungal infection esp. Candida, Aspergillus (24–48 h).SEPSIS CARE BUNDLES

Recent international consensus guidelines on the management of sepsis in critical care have been widely adopted (Table 13.1).

TABLE 13.1 Guidelines for initial treatment of sepsis. Adapted from surviving sepsis campaign1

| Initial resuscitation | Resuscitation goals |

|---|---|

| Begin resuscitation immediately in patients with hypotension or elevated serum lactate >4 mmol/L, do not delay pending ICU admission | CVP 8–12 mm Hg Mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg Urine output >0.5 mL kg−1 h−1 Central venous (SVC) oxygen saturation > 70% or mixed venous > 65% |

| Diagnosis Obtain appropriate cultures before starting antibiotics provided this does not significantly delay antimicrobial administration | Obtain two or more blood cultures (BC) One or more BCs should be percutaneous One BC from each vascular access device in place > 48 h Culture other sites as clinically indicated Perform imaging studies promptly to confirm any source of infection |

| Antibiotic therapy Begin intravenous antibiotics as early as possible and always within the first hour of recognizing severe sepsis and septic shock | Use broad-spectrum antibiotics, one or more agents active against likely pathogens and with good penetration into presumed site of infection Reassess antimicrobial regimen daily to optimize efficacy, prevent resistance, avoid toxicity, and minimize costs Duration of therapy typically limited to 7–10 days; longer if response is slow or there are undrainable foci of infection or immunological deficiencies Stop antimicrobial therapy if cause is found to be non-infectious |

| Source identification and control A specific anatomic site of infection should be established as rapidly as possible and within first 6 h of presentation (see below). | Formally evaluate patient for a focus of infection amenable to source control measures, e.g. abscess drainage, tissue debridement Implement source control measures as soon as possible following successful initial resuscitation (exception: infected pancreatic necrosis, where evidence suggests that surgical intervention is best delayed) Choose source control measure with maximum efficacy and minimal physiologic upset Remove intravascular access devices if potentially infected |

While much of the evidence is low level (based on expert opinion), the recommendations also include some high level evidence, the document as a whole forms a rational and coherent approach to the management of the patient with sepsis. Central to these sepsis care bundles is the need for early effective resuscitation, early effective antibiotic therapy and source control, and where possible, the use of an appropriate ‘biological response modifier’. Currently, activated protein C, (drotrecogin alpha), is the only such agent available (see Septic shock below). The key recommendations are summarized in Table 13.1.

SEPTIC SHOCK

Resuscitation and stabilization

If end-organ failure is compromising respiration (respiratory failure, severe confusion, etc.), early consideration should be given to securing the airway and instituting artificial ventilation. There is a risk, however, that the drugs used to facilitate intubation may cause circulatory collapse. (See Intubation, p. 398.) Therefore, where ventilation is not required immediately, it is often wiser to institute fluid resuscitation prior to attempting intubation and to insert an arterial line to provide accurate blood pressure monitoring. If peripheral arterial cannulation is not feasible, consider femoral or brachial artery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree