16

Infants

Introduction

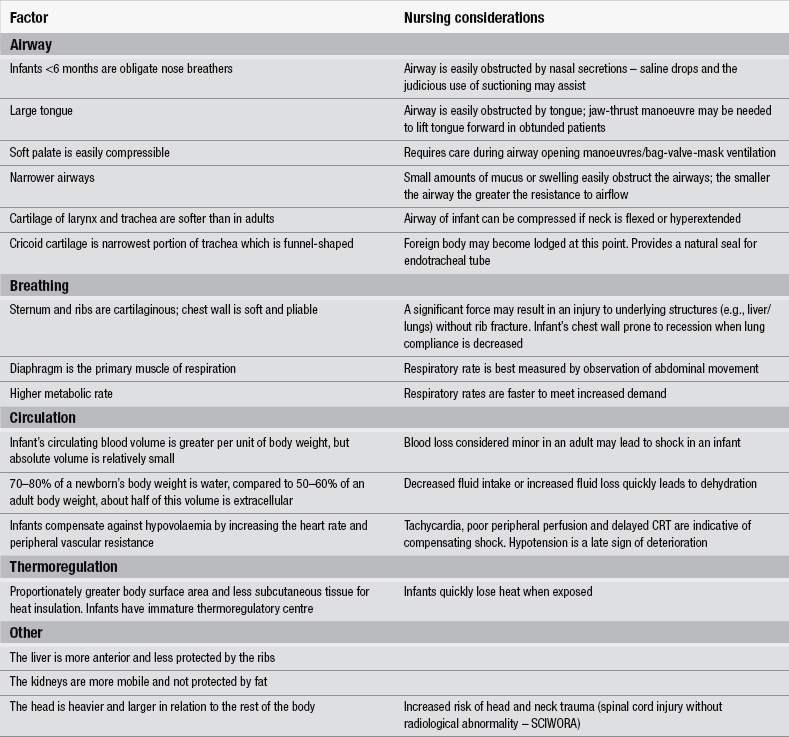

The emergency care of infants requires specific knowledge and skills that can only be gained through study, training and experience. Infancy is defined as the first year of life, with 0–28 days being the neonatal period. Whilst there are some commonalities for assessing patients across all age ranges, it is essential to recognize that infants present with a different range of illnesses and injury patterns from older children and adults. This is due to anatomical and physiological differences and immaturity of the immune system; consequently, different management is required (Table 16.1). There can be little doubt that sick or injured infants are one of the most challenging patient cohorts presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) and parental anxiety can contribute significantly to the challenge. In a typical year up to 50 % of infants will attend an ED (Department of Health 2004). Parental concern should always be taken seriously and the emergency nurse should seek to reassure the accompanying adults by displaying a calm, confident and efficient demeanour, being attentive to their concerns and addressing them accordingly. Infants presenting to the ED with a worrying history may appear quite well at the time they are assessed. Parents should never be criticised for bringing their child to the ED and the provision of comprehensive discharge advice including written information, if available, prior to departure will ensure the most appropriate use of primary and secondary healthcare.

Infant mortality rates in England and Wales have reduced significantly since 1980 due in part to improvements in living conditions, antenatal screening, the childhood vaccination programme and the provision of emergency care (Advanced Life Support Group 2011, Office of National Statistics 2011). Thanks to vaccinations against diphtheria, pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), many previously common life-threatening diseases affecting infants in the UK are now thankfully rare. It is important that the emergency nurse remains alert to infants whose parents have not had access to, or chosen not to take-up these public health measures. It is suggested there is still scope to further reduce infant mortality rates by improving emergency care to bring the UK in line with other developed countries (Advanced Life Support Group 2011).

Development of the normal infant

The emergency nurse must have a reasonable understanding of normal cognitive, behavioural, motor, anatomical and physiological development of the infant. The first year of life is a time of rapid growth and development. The average full-term infant in the UK weighs approximately 3.5 kg and by 12 months has almost tripled this to an average of 10 kg (Advanced Life Support Group 2011). Development from a ‘babe in arms’ to being able to stand unaided and maybe even taking a few steps at 12 months proves an outstanding year of growth. Incorporate into this a couple of meaningful words, a wave goodbye and progressing from an exclusive milk diet to eating solids and you have an impressive period of advancement. Rolling for the first time off an elevated changing table or parental bed reminds parents that each day their baby is growing in ability. Recognizing that infants develop stranger anxiety at around eleven months will also help the emergency nurse to adapt their approach to this exceptionally challenging group.

Developmental tables offer a useful guide to infant’s cognitive, behavioural and motor development that may assist the emergency nurse to identify the infant who is failing to thrive, not reaching developmental milestones or behaving inappropriately (Table 16.2).

Table 16.2

A brief outline of developmental milestones

| Age | Stage of development |

| 4–6 weeks | Smiles to social stimuli |

| 2 months | Smiles and vocalizes when talked to Eyes follow moving person/object |

| 3 months | Holds a rattle when placed in hand Turns head to sounds on level with ear |

| 5 months | Laughs aloud Pulled to sit – no head lag Able to reach and grasp objects |

| 6 months | Sits on floor with support Rolls prone to supine Begins to imitate, for example, cough Held in standing position puts weight on legs |

| 9 months | Crawls on front Stands holding onto furniture |

| 10 months | Waves goodbye Helps parent/carer when being dressed, for example, by holding arms for coat Pincer grip used to pick up fine objects |

| 12 months | Walks holding onto furniture or with one or two hands held Speaks two or three words with meaning |

Airway and breathing

The infant’s airways differ from those of adults and older children in a number of ways that impact upon the response to infection, inflammation and foreign body inhalation. These differences also impact upon the emergency management of the infant’s airway and the equipment used to provide support and stabilization. The infant lungs are immature and have a relatively small surface area for gas exchange. The narrower airways of the infant are at greater risk of compromise even from relatively small amounts of inflammation, secretions and bronchospasm. This is because ‘resistance to airflow is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the airway radius (halving the radius increases the resistance 16-fold)’ (Advanced Life Support Group 2011). Being obligate nose breathers renders infants less than around 6 months old susceptible to airway obstruction from nasal secretions. The trachea of the infant is soft and therefore prone to compression from both flexion and extension of the neck. A collapsed or exhausted infant may need a folded towel or pillowcase placing under the shoulders to prevent flexion of the neck caused by the large occiput.

Circulation

Significant tachycardia is not sustainable and will eventually lead to decompensation. During the decompensatory phase of shock the heart rate will begin to fall and a normal heart rate in a seriously unwell infant may be misinterpreted as an improvement in condition. Bradycardia is a pre-terminal sign. Close attention to heart rate and rhythm, skin colour and temperature, capillary refill time (CRT) and mental status are key to early recognition of compensated shock. A CRT of >2 seconds indicates poor perfusion, although this may be influenced by a number of factors, particularly cold. Capillary refill should be recorded serially to monitor the response of any measures undertaken to improve circulatory status and is recognized as a better indicator of tissue perfusion than systolic blood pressure (Salter & Maconochie 2005).

Assessment

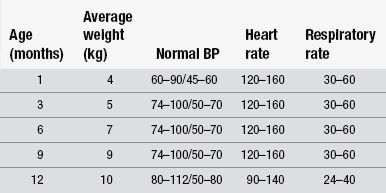

To carry out a full assessment of the sick or injured infant requires specific skills and equipment as well as knowledge of the acceptable parameters for vital signs and factors that affect them (Box 16.1). Normal parameters for an infant’s vital signs change with age (Table 16.3). The measurement of vital signs is more challenging than in older children and certain aspects, such as obtaining oxygen saturations and blood pressure readings can require some persistence and patience (Box 16.2). The assessment should begin from the moment of first visualizing the infant, noting whether he/she is a healthy colour, is awake and alert, sleeping or not responsive and as always followed with a rapid assessment of ABC.

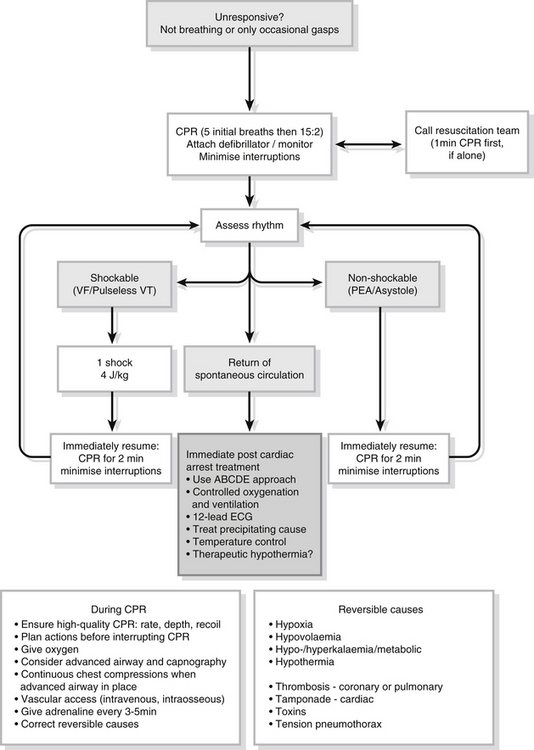

In most cases the first part of the assessment can be performed with the infant on the parent’s lap to minimize distress to both parent and child and provide more accurate readings and is especially important in certain conditions such as croup. If the child is not alert or looks obviously sick the assessment should rapidly move to a trolley/bed/cot where he can be quickly undressed and examined more thoroughly. A degree of common sense must be applied in assessing infants who are obviously sleeping normally, which presents the opportune time to record resting respiratory and heart rate and accurate pulse oximetry; but if there is any doubt regarding responsiveness, immediate attempts should be made to rouse the child. If the child cannot be roused, immediate assistance must be summoned in line with paediatric life support algorithms before assessment of the ABC, with intervention as problems are identified (Fig. 16.1).

The assessment of any infant cannot be deemed complete until he/she has been examined naked to check for rashes, mottling, bruises, mongolian blue spots, injuries, limb deformities, skin temperature, central and peripheral capillary refill time and, wherever possible, an accurate weight obtained. The importance of weighing the infant naked should not be underestimated. All infants and children under 2 years old should be weighed naked in baby scales (Royal College of Nursing 2010). This provides an opportunity to observe the infant’s condition and alert the emergency nurse to any safeguarding concerns such as poor hygiene, bruising and unusual markings. It is also necessary for accurate medication administration, almost all of which given in hospital is calculated according to weight (British National Formulary 2011). The formula: ‘1⁄2 age in months + 4’ may be used to estimate an infant’s weight in kilograms in an emergency. Accurate weighing is the only objective measure of dehydration (Advanced Life Support Group 2011) and poor weight gain or weight loss may indicate chronic or serious illnesses such as cystic fibrosis or congenital cardiac abnormalities. It is always worth plotting the infant’s weight on the centile chart in the parent held record and noting the general trend in weight gain.

The order in which vital signs are measured in routine assessments where urgent intervention is unnecessary is dependent largely on opportunity and the nature of the presenting complaint. As a minimum, the assessment should include measuring the temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, CRT and conscious level. Local guidance should be followed regarding triage tools and paediatric assessment scores which are becoming increasingly popular, however, sound clinical judgement cannot be substituted for such scoring methods and it is much safer to seek senior advice early when there is doubt regarding the accuracy of the score. Where such early warning tools are used staff should be given specific training in their use and limitations (Royal College of Nursing 2007).

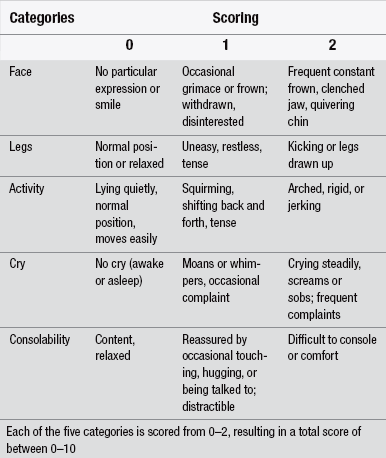

Pain assessment

Pain is often under-recognized and under-treated in the ED (Todd et al. 2002). This can be particularly difficult in infants. The emergency nurse should be trained in the use of pain assessment tools specific to infants and treatment given according to the determined severity. One such tool is the FLACC tool that scores facial expression, leg movement, activity, consolability and crying on a scale of 0–2, the combined total providing a score out of ten (Table 16.4 and Box 16.3). The crying/screaming infant should be presumed to be in pain when none of the usual parental comforting methods such as feeding and rocking are effective. Specific signs such as drawing-up the legs indicating abdominal pain or reluctance to move a particular limb should guide the assessment. Oral sucrose solution and non-nutritive sucking can be used in young infants to provide analgesia during painful procedures such as intravenous cannulation. Consideration of opioid analgesics should be discussed with experienced paediatric-trained staff when simple oral analgesia such as paracetamol and ibuprofen are insufficient.

Table 16.4

The FLACC behavioural pain assessment scale

(Reprinted from Merkel SI et al. (1997) The FLACC: A behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatric Nursing, 23(3):293–297. The FLACC scale was developed by Sandra Merkel, MS, RN, Terri Voepel-Lewis, MS, RN, and Shobha Malviya, MD, at C.S. Molt Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbour, MI. © 2002, The Regents of the University of Michigan.)

Respiratory assessment

The infants’ pattern of breathing must be assessed in terms of rate, rhythm and effort. The number of breaths should be counted for 60 seconds (Royal College of Nursing 2007); this is best achieved by observing abdominal movement. Quick count methods (30- or 15-second counts) or using electronic monitors have been shown to be inaccurate as often as 62 % of the time (Lovett et al. 2005). Worryingly, bradypnoea is almost always missed even though it is indicative of hypoxia and is pre-terminal (Advanced Life Support Group 2011). Tachypnoea may be difficult to count, as often the smaller ‘panting’ breaths are missed (Aylott 2006a). In these circumstances auscultation is necessary. Other clinical signs of respiratory distress include nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles, head-bobbing, intercostal/subcostal/sternal/supraclavicular recession and tracheal tug. See-sawing, which is the paradoxical movement of the chest and abdomen (i.e., the chest falls and abdomen rises during inspiration), represents extremely inefficient breathing and results from significant airway obstruction. Added breath sounds such as grunting, stridor and wheezing may be heard. Grunting is often a sign of significant respiratory or metabolic disease. This is caused by the infant breathing out against a partially closed glottis in order to generate positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) to prevent alveolar collapse. Wheezing is a high-pitched, musical, expiratory sound indicative of lower airway pathology such as in bronchiolitis and other viral infections. It is caused by turbulent airflow through very narrow airways (Aylott 2006b). Wheezing may also be heard in cardiac failure. Stridor is a harsh, low-pitched, usually inspiratory noise indicative of upper airway obstruction, for example in croup or foreign body obstruction.

Cardiovascular assessment

The heart rate in infants should be measured for a full minute by auscultation of the apex beat and electronic measurements should be verified manually (Royal College of Nursing 2007). The apex beat can be heard over the 5th intercostal space in the left, mid-clavicular line. This should be consistent with the brachial pulse, which is palpated on the medial aspect of the upper arm. The carotid and radial pulses are not used routinely in infants as they are difficult to locate. The skin colour and temperature should be consistent over the trunk and limbs; however, when assessing the patient consider the ambient temperature. Decreased skin perfusion can be an early sign of shock. Clinical signs of poor perfusion include peripherally cool skin, pallor, mottling and peripheral cyanosis. CRT is very useful in assessing perfusion. The sternum or forehead are preferred sites (Maconochie 1998) as ambient temperatures can affect peripheral sites. Sufficient pressure to cause the skin to blanch should be applied for five seconds and the length of time for normal colour to return recorded (Castle 2002). Normal capillary refill time is <2 seconds in post-neonatal infants and <3 seconds in neonates. When recording blood pressure, the size of cuff should be at least two-thirds of the length of the upper arm (or lower leg) and the inflatable portion should cover the entire circumference of the limb. This is essential to obtain an accurate reading. It is usually best to leave this measurement to last as it is the least useful data in most cases and tends to be distressing. The first automated blood pressure measurement should be disregarded (Royal College of Nursing 2007). Enquiring about fluid input and output, i.e., drinking well, vomiting, diarrhoea, frequency of wet nappies and observing for moist mucous membranes are all aspects of the cardiovascular assessment.

Advanced paediatric life support

Cardiopulmonary arrest in infants and children is seldom a sudden event and rarely due to a primary cardiac event. It is often the end result of progressive deterioration in respiratory and circulatory function. It usually results from a period of hypoxia and acidosis, which has been caused by respiratory and/or circulatory failure. If pulseless cardiac arrest occurs the outcome is bleak. Early recognition and treatment of decompensating shock to prevent cardiopulmonary arrest is fundamental to successful resuscitation. Thus cardiopulmonary arrest can often be prevented if the clinical signs of respiratory failure and shock are recognized promptly (Wilmhurst & Graydon 2012).

Establish basic life support (Resuscitation Council (UK) 2010a). Oxygenate and ensure the provision of positive pressure ventilation with high-concentration oxygen. Attach a defibrillator or monitor. Look for signs of life. Assess the cardiac rhythm as either non-shockable or shockable:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree