The ANTS system.

Limitations and sources of help

What challenges do people face when returning to work after a break? This is likely to depend on several factors: the reason for leave, the stage the person is at in their career and also the individual.

For those who have been off work because of illness, there is often a degree of uncertainty about how they will be able to cope with the physical and mental demands of being at work. A phased RTW can help here, and seeking advice from an occupational health physician who has experience advising others in similar situations can be reassuring. For those returning from maternity leave, being back at work involves new logistical aspects and a different family dynamic. Days at work and days at home can be very different and it can seem as if they are actually living two different lives. Having robust childcare and a back-up plan for when this does not work is key to being able to leave home at home and concentrate fully on work. Those who are returning from work in another specialty or environment will also have some of the same feelings of unfamiliarity, although perhaps less anxiety about the practical and logistical aspects of being at work.

So what are the potential ‘limitations’? What do people worry about when returning? Here are some of the things that have been mentioned in surveys we have done in the West Midlands.

Practical procedures. From personal experience, I think that the length of time it takes for them to feel familiar again depends upon the level of skill with the procedure beforehand. And actually in reality, these skills usually return very quickly.

Knowledge. It may feel as if you have forgotten lots, but actually you will be surprised at how much knowledge remains. This can be addressed by CPD to prepare for your RTW and hopefully by reading Section 2 in this book.

Management of emergencies. This can be addressed by finding a RTW simulation course or another anaesthetic emergency simulation course such as the MEPA (Managing Emergencies in Paediatric Anaesthesia) course.

Human factors such as situational awareness and decision making or rather, the level of confidence in your own decision making. These can also be addressed on simulation courses. The purpose of a supervised RTW is also to help support the doctor as they refresh these skills.

Supervision of more junior anaesthetists. This can be a source of anxiety when you are finding your feet again. However, teaching is a great form of revision so with a bit of planning and preparation this can help you to refresh your knowledge. It often becomes apparent that you know more than you think.

Earlier in this section we have included some personal experiences and tips that people who have taken time off work have been willing to share. We hope this will help you to realize that any apprehension you feel is very normal.

So why might people not want to ask for help? I can think of a few reasons, but there are likely to be others. We naturally do not want to bother people. We like to be seen as being able to cope and we do not like to feel as if we are creating work for someone else. This can be compounded by a fear of being judged or a perception that people will think we are wasting their time. In the past I think that asking for help might have been perceived as a weakness, although I hope that this is not the case anymore. Indeed, it should be perceived as a strength to ask for help and as professional colleagues we should strive to support each other for the benefit of our patients.

The first step towards getting the help that you need is to acknowledge that you might need to ask for help in the first place. Be accepting of this and please do not be tempted to see it in a negative light. The next step is knowing what sources of help there are. Suggestions listed below are in addition to the published RTW guidance documents described earlier in this section.

1. Mentoring. This can be a valuable source of support. Mentoring is not for people who are failing. It is for everyone to maximize their potential. Please see the section at the beginning of this chapter for more information. Be sure to use a mentor who has been trained.

2. The AAGBI[12]. The AAGBI has a Support and Wellbeing Committee which aims to provide advice, information and support for anaesthetists and to promote a culture of asking for help. You can email the support and wellbeing committee on wellbeing@aagbi.org.

3. The GAT handbook[13]. This has a section on ‘Taking care of yourself’, which has lots of helpful advice for trainees (and consultants too!).

4. The BMA[14]. There is lots of information on the BMA website about the practicalities of returning to work.

5. Colleagues. Colleagues who have been through something similar can be an incredible source of support. Sharing your anxieties and concerns with someone who you know can empathize can be therapeutic.

6. Family and friends. Family and friends may not be able to empathize in the same way as colleagues. However, they can listen and reassure and also help to give some perspective to your concerns.

The bottom line is that everybody needs help sometimes. A RTW after a significant period doing something else is a period of change, and it is normal and should be expected that people will need help and support during this time. You should never worry about asking. It is the right thing to do.

In summary, some helpful tips

Set a goal and a plan of how to reach it. Make sure these are realistic.

Then, take one day at a time.

Be open and honest with those you are working with.

Ask for help if you feel you need it.

Use a mentor for support.

Avoiding adverse outcomes and what to do if one occurs

Adverse incidents affecting patients are something all health professionals strive to avoid. Patient safety is at the forefront of all we do and if this becomes compromised there are numerous consequences that may have knock-on effects on the staff involved. This is particularly pertinent for professionals returning to work after a break for two reasons. Firstly, as mentioned earlier in this section, this is a daunting and stressful time when confidence levels may be low; therefore, an adverse incident will be harder to cope with on an individual level. Secondly, this is a time when individuals may indeed be particularly vulnerable to making an error because of their time out of practice. Appropriate preparation and following RTW programmes should help minimize this but nonetheless an awareness of some of the factors that may help in avoiding adverse outcomes could be beneficial.

James Reason’s approach to human error states there are two ways of viewing the problem: the person approach, focussing on the errors of individuals and blaming them, and the system approach, focussing on working conditions and building defences to avert errors and mitigate their effects[15].

Traditionally in medicine the person approach predominates. This approach is more satisfying than targeting institutions. Thankfully, the shortcomings of this approach are increasingly recognized. It is now often appreciated that it is likely to be a counterproductive way of viewing error, and in fact prevents the development of safer healthcare delivery.

High reliability organizations (those with fewer than their fair share of accidents) appreciate human variability is a characteristic that can actually be harnessed in error reduction. Humans are incredibly adaptable and quick to notice changing patterns. Focussing on these characteristics results in efforts being channelled into considering the possibility of failure and how it may be prevented.

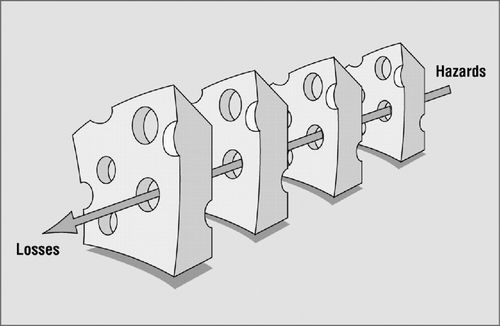

Reason’s Swiss cheese model of system accidents demonstrates the system approach[15]. There should be defences, safeguards and barriers to protect potential victims against harm (layers of cheese, see Figure 5.2). Ideally these defences would be intact but in reality they are like slices of Swiss cheese, having many holes. Although, unlike in the cheese, the holes are always opening, closing and moving. An adverse outcome only happens when the holes momentarily line up to allow a trajectory where hazards can contact victims. This occurs because of either latent conditions or active failures (e.g. mistakes). The active failures can be addressed but will never be eliminated as they are mostly due to human error. It is the latent conditions that can be identified and remedied before an adverse event occurs: this is proactive rather than reactive risk management.

The Swiss cheese model of system accidents.

Professor Martin Elliott, a paediatric cardiothoracic surgeon, proposed 10 commandments for preventing error[16]. These are summarized below and are a good focus for doing all you can to avoid and manage adverse outcomes:

1. Adverse events are important – acknowledge adverse events; do all possible to prevent them; tell the truth to create trust.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree