Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) can be a consequence of multiple and diverse etiologies; the most common encountered in the PICU include cardiac arrest, severe shock, and stroke.

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) can be a consequence of multiple and diverse etiologies; the most common encountered in the PICU include cardiac arrest, severe shock, and stroke. Poor outcomes, defined as death or severe neurologic disability, after cardiac arrest are disappointingly high. Children surviving with HIE have a wide spectrum of disability.

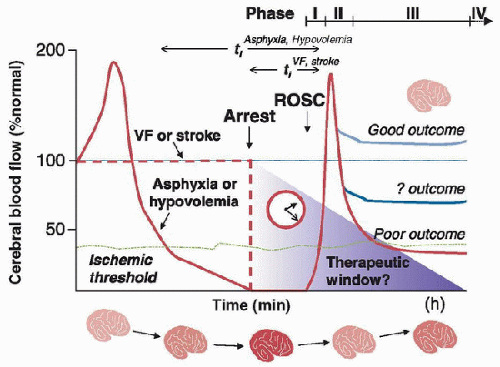

Poor outcomes, defined as death or severe neurologic disability, after cardiac arrest are disappointingly high. Children surviving with HIE have a wide spectrum of disability. Characteristic cerebral blood flow (CBF) patterns occur after cardiac arrest and reperfusion. These include the “no-reflow,” “hyperemic,” “delayed hypoperfusion,” and “recovery” phases. CBF data in animal models suggest that the depth and duration of “delayed hypoperfusion” correlates with the duration of ischemia.

Characteristic cerebral blood flow (CBF) patterns occur after cardiac arrest and reperfusion. These include the “no-reflow,” “hyperemic,” “delayed hypoperfusion,” and “recovery” phases. CBF data in animal models suggest that the depth and duration of “delayed hypoperfusion” correlates with the duration of ischemia. Brain regions that are selectively vulnerable to HIE include the CA1 region of the hippocampus, cortical layers 3 and 5, basal ganglia, and cerebellar Purkinje cells.

Brain regions that are selectively vulnerable to HIE include the CA1 region of the hippocampus, cortical layers 3 and 5, basal ganglia, and cerebellar Purkinje cells. High-quality cardiopulmonary (and cerebral) resuscitation and postresuscitation care are essential. Postresuscitation care should focus on the prevention of secondary brain insults (normoxia, normothermia, normocarbia, normotension).

High-quality cardiopulmonary (and cerebral) resuscitation and postresuscitation care are essential. Postresuscitation care should focus on the prevention of secondary brain insults (normoxia, normothermia, normocarbia, normotension). There are no targeted therapies to prevent HIE, but early after resuscitation a therapeutic window exists for the testing of promising interventions such as hypothermia and other physiologic-based experimentally proven therapies.

There are no targeted therapies to prevent HIE, but early after resuscitation a therapeutic window exists for the testing of promising interventions such as hypothermia and other physiologic-based experimentally proven therapies. sinus thrombosis, or profound shock states. Cardiac arrest due to asphyxia is the most common cause of global HIE in infants and children, while cardiac arrest due to arrhythmias is the most common cause in adults. Focal HIE can result from embolic or thrombotic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage. There are commonalities and important differences between HIE resulting from global and focal insults.

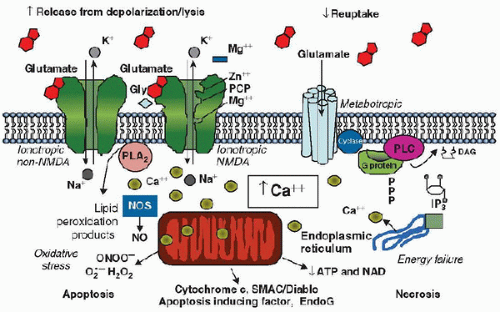

sinus thrombosis, or profound shock states. Cardiac arrest due to asphyxia is the most common cause of global HIE in infants and children, while cardiac arrest due to arrhythmias is the most common cause in adults. Focal HIE can result from embolic or thrombotic stroke, or intracerebral hemorrhage. There are commonalities and important differences between HIE resulting from global and focal insults.mitochondrial dysfunction, energy failure, and initiation of cell death cascades (Fig. 65.1) (1). Neuronal and glial cell death can result from necrotic, apoptotic, and more recently described autophagic pathways (refer to Chapter 56). Each mechanism of cell death has a characteristic morphologic appearance and temporal pattern that can be observed at the microscopic and ultrastructural levels (2). Necrosis is a process characterized by immediate mitochondrial energy failure, leading to cellular swelling, loss of membrane integrity, and a prominent inflammatory response in surrounding tissues. Apoptosis is an energy-requiring process generally requiring new protein synthesis. Enzymatic degradation of cytoskeletal proteins results in cell soma and nuclear shrinkage, and nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is characteristically fragmented via endonucleases. In contrast to necrosis, apoptosis produces minimal inflammation. Autophagic stress can also result in cell death. Autophagy is an adaptive response to starvation, and results in autodigestion of cellular proteins and organelles to feed the cell. Triggering of autophagy after acute insults could potentially be beneficial or detrimental, likely depending on the degree and duration of injury. The role of autophagy after cerebral ischemia is only recently being investigated.

FIGURE 65.1. Cellular mechanisms resulting in cell death and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Prominent contributory mechanisms include excitotoxicity, disturbances in calcium homeostasis, oxidative stress, energy failure, and release of substances triggering cell death pathways. Gly, glycine; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; EndoG, endonuclease G; ATP, adenosine triphosphate. PCP, Phencyclidine; PLA, phospholipases A; PLC, Phospholipase C; DAG, diacyl-glycerol; SMA (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases); C/Diablo, NAD, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. From: Robert S. B. Clark. |

with VT/VF, the survival to hospital discharge is significantly higher versus those presenting with asystole (30% vs. 5%, respectively) (10). This outcome, although less pronounced, appears similar for in-hospital cardiac arrest as children with VT/VF-associated cardiac arrest had the highest survival to hospital discharge (35%), followed by PEA/asystole (27%), and finally late onset VT/VF (11%) (11). Late onset VT/VF is considered a reperfusion arrhythmia (12). The incidence of asphyxial versus VT/VF cardiac arrest reverses with increasing age group. A recent study showed that 7.6% of children aged 1-7 years versus 27% aged 3-18 years presented with VT/VF (13).

TABLE 65.1 REVIEW OF PEDIATRIC CARDIAC ARREST LITERATURE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FIGURE 65.2. Typical patterns of cerebral blood flow (CBF) after cardiac arrest. There are differences between CBF after asphyxial arrest, more predominant in children, and cardiogenic arrest, more prominent in adults. Four typical phases of CBF have been described: no-flow (Phase I), hyperemia (Phase (II), hypoperfusion (Phase III), and recovery (Phase IV). ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; VF, ventricular fibrillation. From: Robert S. B. Clark. |

outcomes can be dismal. These poor outcomes may be related to the prearrest hypoxemia and brain hypoperfusion prior to no-flow ischemia that is seen during asphyxial cardiac arrest (Fig. 65.2). Over half of the children who survive cardiac arrest develop some degree of HIE. A large meta-analysis showed that ROSC from all causes of cardiac arrest was achieved in 13% of pediatric patients. In this study, location of the cardiac arrest had a large impact on survival (24% for children with in- hospital cardiac arrest and 9% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest) (7). Similarly, in a multicenter, prospective, observational study of children, the in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival was 49% and 38%, respectively (6). The leading cause of death was neurologic in 69% of the out-of-hospital arrest cohort and cardiovascular in the in-hospital arrest cohort (Table 65.1).

outcomes can be dismal. These poor outcomes may be related to the prearrest hypoxemia and brain hypoperfusion prior to no-flow ischemia that is seen during asphyxial cardiac arrest (Fig. 65.2). Over half of the children who survive cardiac arrest develop some degree of HIE. A large meta-analysis showed that ROSC from all causes of cardiac arrest was achieved in 13% of pediatric patients. In this study, location of the cardiac arrest had a large impact on survival (24% for children with in- hospital cardiac arrest and 9% for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest) (7). Similarly, in a multicenter, prospective, observational study of children, the in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival was 49% and 38%, respectively (6). The leading cause of death was neurologic in 69% of the out-of-hospital arrest cohort and cardiovascular in the in-hospital arrest cohort (Table 65.1).of HIE until later when developmental milestones are not met and should have long-term developmental screening. Although outcome after cardiac arrest is poor for any age, a Japanese study of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that adolescents, who were more likely to have a witnessed arrest and shockable rhythm, had a superior 1-month survival rate (11%) compared with younger children (1%-2%) (16).

blood flow (Phase IV) (32,33,34). Studies in pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest demonstrate that CBF varies for different brain regions within each phase. In the setting of pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest, progressively increased insult durations diminish the intensity of the hyperemia phase in all regions, with hypoperfusion predominating at longer insult durations (29).

blood flow (Phase IV) (32,33,34). Studies in pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest demonstrate that CBF varies for different brain regions within each phase. In the setting of pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest, progressively increased insult durations diminish the intensity of the hyperemia phase in all regions, with hypoperfusion predominating at longer insult durations (29). hippocampus, and striatum. It is hypothesized that vasospasm, perivascular edema, and increased blood viscosity play a role in the development of this “no-reflow” phenomenon.

hippocampus, and striatum. It is hypothesized that vasospasm, perivascular edema, and increased blood viscosity play a role in the development of this “no-reflow” phenomenon.Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree