Key Clinical Questions

What are the signs and symptoms of hypothermia?

What are the most common causes of hypothermia?

Does intoxication associated with hypothermia suggest a better or worse prognosis?

What are the dangers associated with hypothermia?

Who is most likely to die from hypothermia?

A 54-year-old man was brought to the hospital after being found unresponsive in his apartment. His family noted that he had been recently hospitalized for pneumonia and had been released from the hospital 3 days earlier. The ambient temperature of the apartment was normal per the EMS report. His temperature was 32°C, his heart rate was 50 beats per minute, his respiratory rate was 14 breaths per minute, and his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg. His head and neck, cardiovascular, and abdominal examinations were normal. His skin was cool but warmer than expected given his core temperature; pulses were present in all extremities. There were decreased breath sounds and egophony in the right lower lobe; the signs of consolidation were confirmed by chest X-ray. What is the cause of this man’s mental status changes and what is his prognosis? |

Introduction

Vital signs are routinely measured for all hospitalized patients on admission, during nursing shifts and when infusions are being administered. Clinicians should be able to recognize when abnormal temperatures require immediate action to avoid adverse consequences that may be potentially life-threatening.

Hypothermia Presentaions

Core body temperature is tightly regulated between a normal diurnal range of 36.0°C and 37.5°C. Temperatures below 36.0°C are considered abnormal. Patients admitted to the inpatient service frequently have temperature abnormalities on admission or may develop them during the hospital stay.

Because of potential life-threatening causes, it is essential to obtain an accurate measurement of core body temperature. Although temperature is most accurately measured by the gold standard methods of intravascular, esophageal, or bladder thermistors, the most commonly used clinical methods are rectal, oral, and tympanic membrane measurements. Axillary measurement routinely underestimates core body temperature and lacks precision; therefore, it is not recommended. It should be noted that oral measurements can be influenced by eating, drinking, breathing devices, tachypnea, and mouth breathing. Rectal temperatures may be two to three tenths of a degree Celsius higher than actual core body temperature.

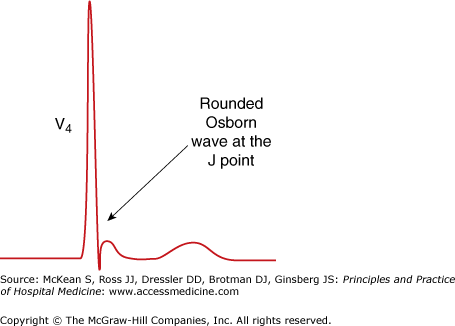

Exposure hypothermia is defined as an unintentional fall in core body temperature below 35.0°C from exposure to a cold environment. The most common cause is lack of shelter, warm clothing, or heat during the winter months. When environmental exposure to cold ambient temperatures is not obvious, making the diagnosis can be challenging because the presenting signs are often subtle and associated with numerous potential diagnoses. The initial phase of hypothermia usually consists of shivering, tachycardia, tachypnea, and peripheral vasoconstriction. Shivering may disappear if hypothermia is prolonged or progresses to severe levels. Other signs include confusion, drowsiness, dysarthria, decreased coordination, and arrhythmias. In moderate hypothermia (28.0°C–32.0°C), pupillary dilatation, hallucinations, and the phenomenon of paradoxical undressing—the removal of clothes as core temperature drops—may be present. Cardiac manifestations such as bradycardia and arrhythmias begin to develop. Electrocardiographic (ECG) findings, such as a prolonged QT interval as well as an Osborn wave, sometimes referred to as a J wave, may be present (Figure 92-1). The Osborn wave is also seen in severe hypercalcemia, but the ECG is distinct from a patient with hypothermia. The QT interval is usually shorter in hypercalcemia, and the patient is more likely to be tachycardic from volume depletion. Movement artifact from shivering may also be present in patients with hypothermia, especially in the limb leads with relative sparing of the precordial leads.

|

Severe (<28.0°C) hypothermia may result in coma, hypotension, extreme oliguria, and peripheral areflexia.

At any stage of hypothermia, the precapillary vascular resistance may fail, with resultant vasodilation. The increased blood that follows may cause sufficient warming to restore vascular function and reinstate local vasoconstriction. The oscillation between dilatation and constriction is known as the Lewis-Hunting reaction and occurs primarily on the fingertips, toes, ears, and face resulting in paroxysms of flushing.

Finally, there are hematologic changes associated with hypothermia that are important. Cold directly inhibits the enzymatic reactions of both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways of the clotting cascade. At low temperatures, patients may have significant bleeding or hemorrhage.

Nonexposure hypothermia should be considered sepsis until proven otherwise. The peripheral vasodilatation associated with progressive sepsis results in the inappropriate liberation of body heat, lowering the body’s temperature. Unusual causes of nonexposure hypothermia include metabolic disturbances that result in downregulation of the body’s metabolic rate. Euthyroid sick syndrome, hypothyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency are the most common.

Hypothermia is ultimately the result of a mismatch between heat production and heat loss, in the same way that underheating a home is due to a mismatch between heat production from the home’s fireplace and heat loss from the home’s insulation, or lack thereof. The resultant problems stem from three components: There is not enough wood (fuel), not enough fire (metabolism), or not enough insulation (heat loss).

The fuel (wood) for basal metabolism must be adequate in order to generate heat. Hypoglycemia, malnourishment, and decreased muscle mass contribute to hypothermia as the patient has too little fuel to generate heat. The hypothermia of hypoglycemia is a result of glucopenia in the hypothalamus, resulting in a down-adjustment of the thermal set point that is presumptively to reduce metabolic rate in the setting of inadequate fuel supply. The chronic malnourishment of alcohol abuse places alcoholics at even greater risk of hypothermia.

If fuel supplies are adequate, the body’s metabolism

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree