HYPERTENSION

ERIKA CONSTANTINE, MD AND CHRIS MERRITT, MD, MPH

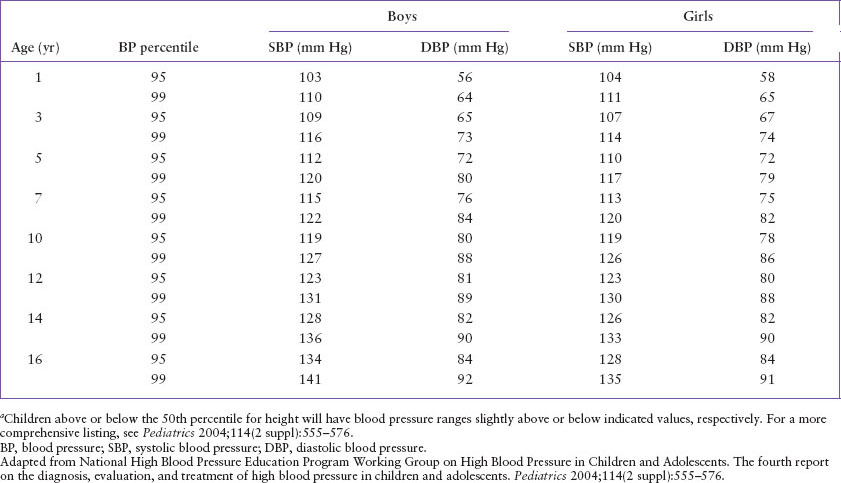

Until recently, the prevalence of hypertension in the pediatric population had been relatively low. Recent trends in childhood obesity, however, appear to be linked to the observation of an overall increase in blood pressure values seen in children. The Fourth Report on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents, a national consensus statement published in 2004, suggests that a child with three or more blood pressure measurements above the 95th percentile for age, height, and gender should be considered hypertensive. Stage 1 hypertension is defined as blood pressure values that range from the 95th percentile to 5 mm Hg above the 99th percentile. Those with blood pressure measurements of 5 mm Hg or more above the 99th percentile are considered to have stage 2 hypertension (Table 33.1). Hypertensive urgency is a significantly elevated blood pressure level that may be potentially harmful but is without evidence of end-organ damage or dysfunction. Hypertensive emergency describes an elevated blood pressure level associated with evidence of secondary organ damage such as hypertensive encephalopathy or acute left ventricular failure. Hypertensive urgencies ordinarily develop over days to weeks, whereas hypertensive emergencies generally develop over hours.

Standard blood pressure nomograms in children are based on auscultatory measurements of blood pressure levels using the right arm supported at the level of the heart. Appropriate blood pressure cuff size is essential for accurate measurement. The inflatable rubber bladder should be long enough to completely encircle the circumference of the arm (overlap is acceptable). Bladder width should be approximately 40% of the arm circumference at a point halfway between the acromion and the olecranon. A narrow cuff can produce falsely elevated readings, while an overly broad cuff may produce readings that are falsely low.

Auscultation remains the recommended method for blood pressure determination in children. Current guidelines recommend that the disappearance of the fifth Korotkoff sound should be used to define diastolic blood pressure. In the emergency department (ED) setting, however, sphygmomanometer readings are sometimes difficult to perform, particularly in neonates and very young children. In such cases, an oscillometric device, which measures the mean arterial pressure and calculates systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, may be used. Because blood pressure calculations by this method may vary widely from device to device, any abnormal reading should be repeated by auscultation.

In the ED, where children are often stressed or agitated by an unfamiliar environment or underlying illness, abnormally high blood pressure readings are not uncommon. These measurements should be repeated after a brief period of quiet rest.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY/DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hypertension may be either primary or secondary in nature. Primary, or essential, hypertension is a condition in which no underlying disease can be identified. The increasing frequency of primary hypertension in the pediatric population is believed to be largely attributable to the increases in body mass index, sedentary lifestyle, and high-salt and high-calorie diets of today’s children. Nonetheless, essential hypertension is a diagnosis of exclusion and is rarely the cause of hypertensive urgencies or emergencies.

Secondary hypertension can be the result of an underlying pathologic process, such as a cardiovascular, renal, endocrine, toxic, or central nervous system disturbance. Disruptions in the renin–angiotensin system, volume overload or sympathetic stimulation by tumors, drugs, or other processes, may all contribute to the development of hypertension.

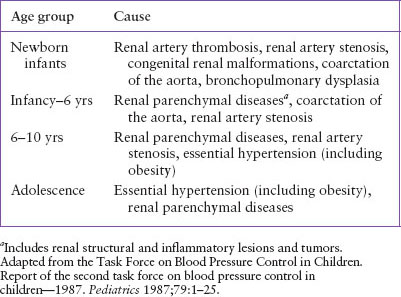

The differential diagnosis of hypertension changes with the age of a child (Table 33.2), with younger children being more likely to have a discernable cause for their hypertension (Table 33.3). In adolescent girls, oral contraceptive pills may be a cause of hypertension, and in all age groups, drug- or toxin-induced hypertension should be considered.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

Children with a persistently elevated blood pressure level in the ED require a brief but thorough history and physical examination, with emphasis on detecting an underlying cause for hypertension and eliciting signs and symptoms of end-organ damage resulting from the hypertensive process. In the absence of concerning findings in the history or physical examination, the child with mild or moderate hypertension should be referred for follow-up with the primary care physician. Although it is appropriate to initiate the process of patient education in the ED regarding weight loss, dietary salt reduction, and exercise, a definitive diagnosis of hypertension should not be offered until elevated blood pressure has been confirmed on several occasions.

The workup of a child with severe hypertension requires careful evaluation for the presence of clinical findings that may represent either the primary cause of the elevated blood pressure or the secondary systemic effects of hypertension. Histories of frequent urinary tract infections, unexplained fevers, hematuria, dysuria, frequency, or edema all suggest renal disease. Previous umbilical artery catheterization increases the risk of renal artery stenosis or thrombosis. Ingestion of prescription, over-the-counter or illicit drugs, or rapid withdrawal of some antihypertensive medications, may support the diagnosis of drug-related hypertension. A history of sweating, flushing, palpitations, fever, and weight loss may suggest a pheochromocytoma.

TABLE 33.1

BLOOD PRESSURE LEVELS (95TH AND 99TH PERCENTILES) FOR CHILDREN OF AVERAGE HEIGHTa (50TH PERCENTILE) AT SELECTED AGES

Physical examination should concentrate on identifying involved organ systems, paying particular attention to cardiovascular, renal, and central nervous systems. The cardiac examination should seek evidence of congestive heart failure (CHF) and pulmonary edema. Absent or decreased femoral pulses are suggestive of aortic coarctation. Abdominal examination may reveal the presence of a bruit or renal mass such as Wilms tumor, implicating a renovascular cause for the hypertension. Peripheral edema may suggest volume overload from renal or cardiac failure. Neurologic evaluation should include observation for sensorimotor symmetry and appropriate cerebellar function. Funduscopic examination for hypertensive changes such as hemorrhages, infarcts, and disc edema should be conducted, in addition to testing the pupillary light reflex and visual acuity.

TABLE 33.2

COMMON CAUSES OF HYPERTENSION

Initial investigations for severe hypertension in the ED should be limited to the most basic of tests. Blood studies including a complete blood cell count, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and urinalysis are usually warranted. In addition, a urine culture should be considered in all girls and in boys with known renal pathologic conditions. A chest radiograph and electrocardiogram may help detect the presence of CHF or ventricular hypertrophy. If there are concerning findings on the initial cardiovascular examination, an echocardiogram may also be warranted. Additional studies are rarely part of the routine ED assessment of hypertension.

When the cause of hypertension is not readily apparent, a stepwise evaluation of the most common organ systems is indicated (Fig. 33.1)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree