20 Herbal and Nutritional Supplements for Painful Conditions

Herbs and supplements are widely used by patients in pain.1 Throughout this chapter, mechanisms of action and efficacy, dosing, and safety information will be provided for each herb, supplement, and natural product for the pain syndromes for which research literature supports their use. For herbs, the medicinal portion of the plant will also be given because different parts of a plant may have different constituents and clinical effects. This chapter is meant to provide an overview, and practitioners not already trained in natural medicine should seek additional education to become proficient in the use of natural products.

Natural substances offer many potential benefits for helping treat patients with pain. First, they often have long histories of use (thousands of years in some cases; the Ebers Papyrus, arguably the oldest book in the world, consists of a materia medica of traditional Egyptian medicine2), and one could argue these substances are among the best tested and most “evidence-based” medicines available.3 Second, they are largely nontoxic, although there are exceptions.4 One study found that over a 10-year period, only two deaths in the United States could be linked to herbal medicines.5 Third, they are often cost effective, again, with exceptions. Finally, they act on multiple pathways, some of which are not addressed by any other existing therapies.6 Study of the mechanism of action of some natural treatments has led to breakthroughs in the understanding of pain pathophysiology and to the development of entirely new categories of medications. For example, investigation of capsaicin brought about enhanced understanding of vanilloid receptors, TRPV1, unmyelinated C fibers, substance P, and novel topical treatments for pain syndromes.7

Western Herbal Medicine: Complexity and Synergy

Herbs have been an important part of Western medicine for thousands of years.8,9 Herbs contain hundreds of different compounds, and traditional medicine theorizes that the constituents of medicinal plants act synergistically.10 Many studies support that complex herbal extracts often have effects that are distinct and/or greater than those of their single isolated constituents.11

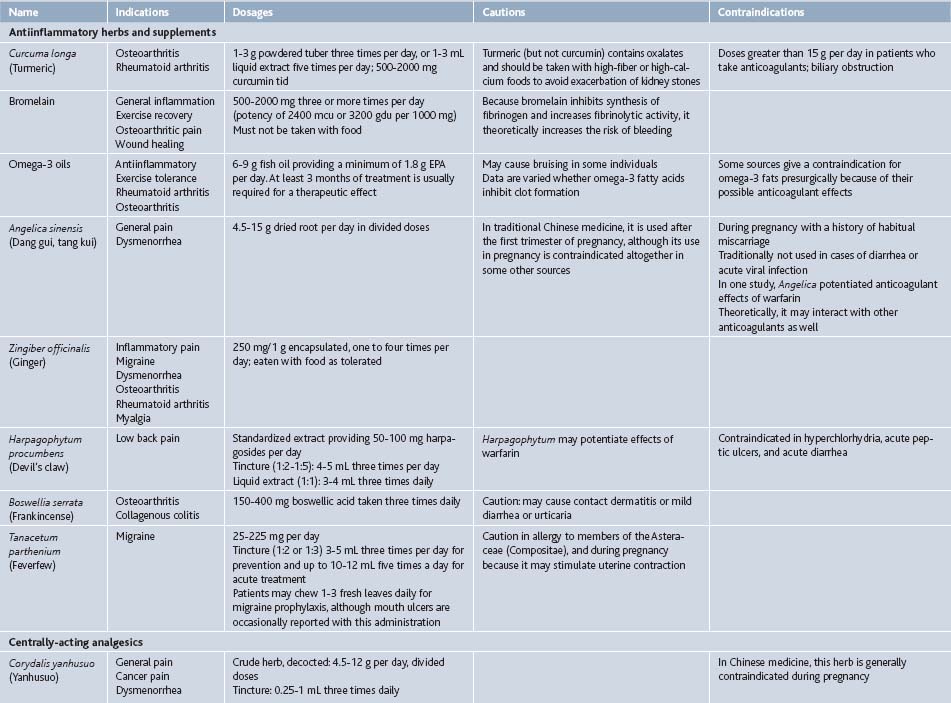

In some cases, isolated compounds or highly refined extracts with just a few constituents such as silymarin, a complex of three flavonoligans from Silybum marianum (milk thistle) seed, or curcumin, a mixture of three resinous polyphenols from Curcuma longa (turmeric) rhizome, are used clinically. It is not clear if these offer advantages over more complex, less concentrated extracts, given a near total lack of comparative studies, but such extracts do satisfy the demand for uniformity, simplicity, and patentability prevalent in a market-driven health care system and society.12 Throughout this chapter, both refined and crude herbal extracts will be listed for completeness, although often it is unknown which form is superior (Table 20-1).

Chinese Herbal Medicine: Ancient and Modern

Chinese medicine is one of the most ancient healing systems on the planet.13,14 Based on a distinctive physiology quite unlike Western medicine, it is still in use today. Herbs play a central role in Chinese medicine, although acupuncture is more widely accepted in Western society. Unlike in Western cultures, herbs in traditional Chinese medicine are almost always given in complex formulas,15 as it was observed that combining herbs produces a stronger, more specific therapeutic effect, and that herbs used together mitigate some of the adverse effects they may engender as single entities. Formulation is still the most common way to prescribe Chinese herbs.16 Nevertheless, biochemical and pharmaceutical research techniques have been extensively applied to Chinese herbs, and now single-herb medicines or isolated constituents extracted from single herbs are used more widely. Caution is warranted with these much more recent innovations, and the traditional formulas are preferred in most cases. Many of these same arguments could be made about traditional medicine systems from around the world, such as Ayurveda and Unani-Tibb in South Asia, or Native American medicine.

Antiinflammatory Herbal Medicines

Curcuma Longa (Turmeric)

The rhizome of Curcuma longa is ground or tinctured (1:2 ratio, >45% ethanol content)6 to make medicine. Most supplements use curcumin, a mixture of lipophilic polyphenolic compounds including diferuloylmethane, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin found in the rhizome. It is traditionally used for pain and has been shown to modulate inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ.17

Bromelain

Bromelain is a mixture of enzymes derived from pineapple. Its effects are mainly a product of its proteolytic activity, which stimulates fibrinolysis by increasing plasmin, but bromelain also has been shown to prevent kinin production and to inhibit platelet aggregation.22 Because its mechanism of action is generally antiinflammatory, rather than specific to a particular disease process, bromelain is used to treat a variety of pain and inflammatory conditions. When given to treat pain, it must be administered away from food because it will act as a digestive enzyme if consumed with food.

Omega-3 Oils

Omega-3 essential fatty acids are used by the body to form cell membranes and antiinflammatory prostaglandins, among other important molecules. Murine studies indicate that these fats produce resolvins and protectins, novel lipids with antiinflammatory properties. Although these fatty acids do not act specifically on nociceptive pathways, their administration has the well-documented effect of reducing inflammation in the body.30

A study comparing two marine oils (seal and cod liver oils) found no difference in their efficacy,31 suggesting that the origin of the fatty acids is less important than their EPA/DHA content. Fatty acid source is a concern with regard to heavy metal and PCB content of the supplements, and only products that employ third-party verification of purity should be given.

Angelica sinensis (Dang Gui, Tang Kui, Dong Kuai)

The root is used as medicine and the herb is tinctured, decocted, or powdered and encapsulated. In China, it is also injected locally into areas of low back and postsurgical pain with significant improvement of symptoms.36 Angelica is commonly used in Chinese medicine for gynecologic complaints, including dysmenorrhea. Active constituents include ligustilide, which has been demonstrated in murine studies to be antinociceptive and antiinflammatory.37

Zingiber officinalis (Ginger)

The rhizome of Zingiber has been used in traditional Asian medicines, including Chinese and Ayurvedic herbalism, for millennia. Today, it is administered as encapsulated powder, in decoction, food, or tincture. Ginger is more commonly used for treatment of digestive complaints than it is for pain, but has been shown to inhibit prostaglandin and thromboxane formation in platelets39 and serotonin receptors in vivo. In vitro studies of human synoviocytes have demonstrated that Zingiber extract inhibits TNF-α activation and cyclooxygenase-2 expression.40

Harpagophytum procumbens (Devil’s Claw)

This herb is native to southern Africa, and it grows in a fairly limited distribution, making it somewhat threatened in the wild. Because of this, only cultivated material should be purchased. The tuber is used therapeutically, and active constituents appear to be iridoid glycosides including harpagosides. This herb is usually administered as an aqueous or alcohol extract. Mechanism of action is unknown, but appears to be mediated via the central nervous system with possible peripheral antinociceptive effects. A rodent study found that its effects were attenuated by naloxone administration, suggesting that it acts at least in part via opioidergic pathways.47

Boswellia serrata (Frankincense)

Tanacetum parthenium (Feverfew)

The leaf is typically used as medicine and is eaten fresh or taken as tea, encapsulated crude herb or tincture. It appears to act by inhibiting formation of prostaglandins in the arachidonic acid pathway, inhibiting serotonin and histamine secretion, preventing platelet aggregation, or by reducing vascular response to vasoactive amines. Parthenolide is supposedly one of the major active constituents and appears to inhibit arachidonic acid release, but studies using parthenolide alone do not yield the clinical results obtained by administration of the whole herb.52

Centrally-Acting Herbs and Supplements

Corydalis yanhusuo

A member of the poppy family, Corydalis yanhusuo is one of traditional Chinese medicine’s chief herbs for relieving pain. The rhizome is used. Like many Chinese herbs, it is traditionally taken as an aqueous extract (i.e., decocted as tea, although it is also given as tincture [1:3 to 1:5]) or in pill or capsule form. Substitution of other species of Corydalis for C. yanhusuo is not recommended because their actions appear to differ. Its primary active constituents are alkaloids, including berberine, corydaline, and tetrahydropalmatine. Various studies have compared Corydalis extracts to morphine and findings vary, indicating that they have from 1% to 40% the analgesic effect of morphine.16,22,54

Cannabis sativa

Research into the mechanism of cannabinoid receptors in the body is ongoing, but suggests that they play a role in the pain-mediating effects of cannabinoids. Two major types of receptors, CB1 (found primarily in the nervous system, both centrally and peripherally) and CB2 (found in nonnervous tissues, including immune cells), have been identified.57

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort)

The aerial parts of the plant are used as medicine. Hypericum may be given internally as a tincture, decoction, or encapsulation, or used topically as a lotion. Hypericin, hyperforin, and flavonoids are thought to be the major active constituents. This herb is most commonly associated with treatment of depression but eclectic physicians used it topically as a vulnerary and internally to treat neurogenic pain, including sciatica and rheumatic pain.71

Two murine studies demonstrated antinociceptive properties of H. perforatum. These properties are dose-dependent in a bell-shaped trend, i.e., therapeutic effect may only be derived from doses that are neither too low nor too high. Hypericum’s mechanism of nociceptive action seems to be due to hypericin’s inhibition of protein kinase C and to interaction with opioid receptors, although other receptor classes may be involved.72 Opioid receptor involvement is supported by the finding that the herb significantly enhances the effects of concurrently administered morphine without altering serum morphine levels.47