Figure 11.1 Anatomy. (a) The orientation of the gallbladder underneath the liver. Important surrounding structures to note are the portal vein, IVC, and the duodenum. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press. (b) The gallbladder in relation to the stomach and liver; the liver is lifted up for visualization. The gallbladder is divided into the neck, body, and fundus. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press. (c) The relationship of the gallbladder, and the cystic, hepatic, and CBDs. (Illustration by Laura Berg, MD).

Technique

Point-of-care questions

Transducer selection and orientation

For most children, using the low-frequency (2–5 MHz), curvilinear transducer or the high-frequency (5–10 MHz), linear transducer is adequate. At times, it may be helpful to use the phased-array transducer in order to view the gallbladder in between the ribs if there is difficulty in obtaining images.

Transducer placement can be at the subcostal region, right flank, or the “X-7” approach. In the subcostal region, the indicator is oriented towards the patient’s right shoulder. Begin scanning at the subxiphoid region, and slide subcostally towards the patient’s right side (Figure 11.2a). At the right flank, orient the transducer with the indicator towards the patient’s head (Figure 11.2b). In the “X-7” approach, the transducer is placed at the right anterior chest, 7 cm to the patient’s right. This is generally in the midclavicular line, using the intercostal space to scan. Initially the indicator is oriented in the transverse plane, towards the patient’s right side (Figure 11.2c). Regardless of the approach to scanning, the gallbladder must be visualized in two views: its long-axis and its short-axis. Once the gallbladder is identified in its short axis the transducer can be rotated clockwise in order to visualize the gallbladder in its long-axis.

Figure 11.2 Ultrasound examination of the gallbladder. (a) The subcostal approach, with the indicator oriented towards the patient’s right shoulder. (b) The right flank. The patient may be supine or in the left lateral decubitus position, with the indicator pointing cephalad. (c) “X-7” approach, with the transducer in the transverse plane, with the indicator towards the patient’s right side. (d) Rotating the patient in the left lateral decubitus position may improve visualization of the gallbladder.

Patient position and preparation

The initial position can be supine, but, frequently, to visualize the gallbladder and liver properly the patient may need to be placed in the left lateral decubitus position where gravity brings the gallbladder anterior (Figure 11.2d). If it is still difficult to locate the pertinent structures, having the patient lie nearly prone on the transducer may help. A deep inspiration pushes the liver and gallbladder inferiorly and may make them easier to locate. Rolling the patients also helps distinguish a polyp from a stone and also whether a stone is simply sitting near the neck of the gallbladder or is impacted in the neck.

Traditionally, it was taught that it was best to visualize the gallbladder after a fast of four to six hours; at this point it will be filled with bile and easily seen. If the patient has just eaten, the gallbladder may be difficult to visualize since contraction may have occurred. This has recently come into question, with a study showing that no significant difference in gallbladder size is seen after ingestion of a fatty meal. Plus, fasting in the emergency department setting would make the examination prohibitive.

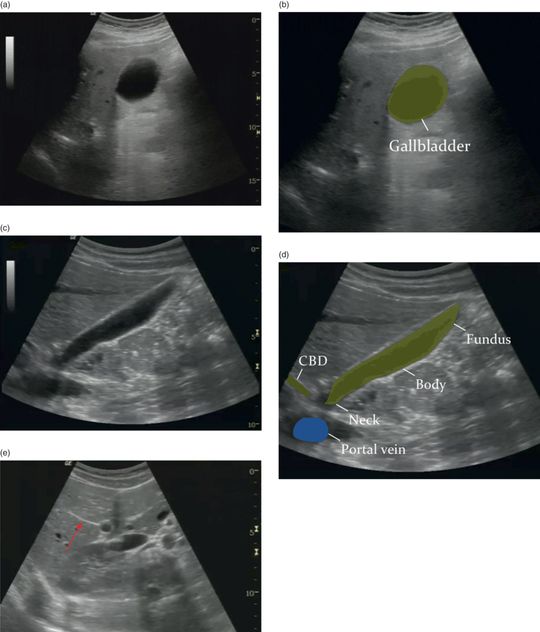

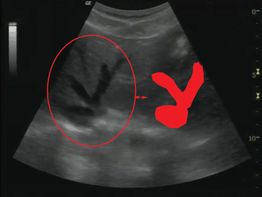

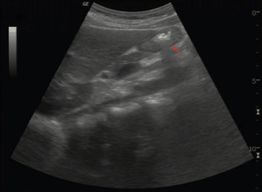

Ultrasound imaging

By applying gentle pressure and fanning the through the liver, the gallbladder should be visualized. If it is not visualized readily, slide the transducer down along the costal margin scanning through the dome of the liver. Sweep through the entire gallbladder in the transverse view (Figure 11.3a,d). When completed, rotate the transducer 90° to obtain the longitudinal view of the gallbladder. In the longitudinal view the gallbladder neck, body, and fundus can be visualized (Figure 11.3c,d). The major lobar fissure leads to the gallbladder, and can serve as a landmark in identifying the gallbladder (Figure 11.3e) and right portal vein should appear as an exclamation point (Figure 11.3d,e). Because it is filled with bile, a normal gallbladder has several of the sonographic qualities of a cyst: smooth, thin, well-defined walls, an anechoic internal lumen, bright echogenic posterior walls, and posterior acoustic enhancement (Figure 11.4). Frequently, the tear-drop shaped gallbladder may contain one of a few variant folds. A junctional fold can be seen as an echogenic line in the middle of the gallbladder (Figure 11.5a). A Hartmann’s pouch is a fold near the neck of the gallbladder, where gallstones can collect (Figure 11.5b). A Phrygian cap is a small fold near the distal end of the fundus (Figure 11.5c).

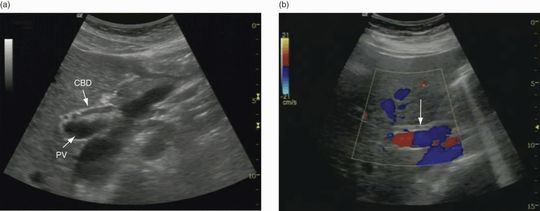

Figure 11.3 Normal gallbladder. (a) Transverse view of a normal gallbladder. (b) Illustration depicting transverse view of the gallbladder. (c) Longitudinal view of a normal gallbladder. (d) Normal gallbladder demonstrating the neck, body, and fundus. The gallbladder in the longitudinal view should appear as an “exclamation point”, with the gallbladder and portal vein (PV). The CBD can also be seen as parallel lines anterior to the PV. (e) Major lobar fissure leading to gallbladder (arrow). Illustrations by Laura Berg, MD.

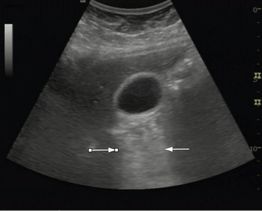

Figure 11.4 Gallbladder demonstrating posterior acoustic enhancement (arrows).

Figure 11.5 Normal variants of the gallbladder. (a) A junctional fold in the middle of the gallbladder (arrow). (b) A Hartmann’s pouch near the neck of the gallbladder (arrow). (c) A Phrygian cap seen at the fundus of the gallbladder (arrow).

The liver is straightforward to visualize with sonography. Its dense structure serves as a good sonographic window, allowing the other portions of the right upper quadrant to be visualized. It appears dense on ultrasound with multiple small and large anechoic “holes” distributed throughout the organ. These are the many ducts and vessels that comprise the liver and give it a homogeneous “salt and pepper” appearance (Figure 11.6a). When this appearance is disrupted, an abnormality probably exists in the liver, such as cancer or hepatitis (Figure 11.6b). The IVC is the largest vessel seen in this area; its course can be traced from the lower abdomen, posterior to the liver, where it enters the right atria (Figure 11.7). The right, middle, and left hepatic veins branch off the IVC as it enters the abdomen; this branching has been nicknamed the “Playboy bunny” sign because it takes the appearance of rabbit ears (Figure 11.8). Like the gallbladder, the duodenum lies on the lower left border of the liver. Frequently it is mistaken for the gallbladder, but observing it for a time should demonstrate peristalsis (Figure 11.9). The portal vein is the largest component of the portal triad, with hyperechoic walls that make it easy to locate in the liver. If traced out further into the liver, the portal vein branches off into the right and left portal veins. The second structure in the portal triad, the hepatic artery, has a limited role in emergency sonography. The neck of the gallbladder is continuous with the cystic duct, which merges with the hepatic ducts coming from the liver to form the CBD (Figure 11.10). Sonographically, the CBD usually lies between the gallbladder and the portal vein. It can be seen as two hyperechoic lines running on top of and parallel to the portal vein (Figure 11.11a). Often it is difficult to distinguish the CBD from the hepatic artery or other vessels in the area. Magnifying the area with your machine’s zoom capability can help enhance the smaller portions of the examination. Another helpful way to recognize the duct is to use color Doppler, since the CBD will not demonstrate any color flow (Figure 11.11c). In transverse view, the portal triad takes on the appearance of three circles, affectionately called the “Mickey Mouse” sign (Figure 11.12).

Figure 11.6 Normal liver. (a) Normal liver with homogeneous appearance. (b) Liver demonstrating cancer metastases (arrows). Notice the very heterogeneous appearance of this diseased liver.

Figure 11.7 Inferior vena cava (IVC). Inferior vena cava emptying into the right atria (RA). The liver and diaphragm are seen in the upper portion of this image.

Figure 11.8 Hepatic veins. The branching hepatic veins give the appearance of a bunny with ears, referred to as the “Playboy bunny” sign.

Figure 11.9 Duodenum. The duodenum (arrow) is frequently mistaken for the gallbladder because of its appearance and location.

Figure 11.10 Biliary ducts. The cystic duct (arrows) is seen at the neck of the gallbladder.

Figure 11.11 Common bile duct (CBD). (a) A sagittal view of the CBD is seen superior to the portal vein (PV). (b) Color Doppler can be utilized to locate the CBD. Note how the CBD does not demonstrate color flow (arrow).

Figure 11.12 Portal triad. (a) Drawing demonstrating the “Mickey Mouse” sign of the portal triad. (b) Portal triad on transverse image demonstrating the “Mickey Mouse” sign: portal vein (PV), common bile duct (CBD), hepatic artery (HA).

Once the gallbladder and its surrounding structures are located, it should be determined whether there is the presence or absence of certain sonographic features to assess for acute cholecystitis:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree