Healthy Growth and Development of the Toddler

Susan J. Brillhart MSN, RN, CS, PNP

INTRODUCTION

The toddler, ages 1 through 3, can be a delightful, engaging, and exasperating individual. Some toddlers are timid, some very spirited, and all will need to be very involved in the plan of care. Toddlers can be shy, inquisitive, and dependent, yet they enjoy asserting their opinions. One toddler has the ability to exhaust a whole group of adults. Toddlers will challenge adults with very definite needs and wants, yet they may lack the verbal skills to convey such wishes clearly. Their psychosocial growth is progressing rapidly, while their physical growth is slowing. Their health problems are, hopefully, few. Care of the toddler is true family-centered care, because few toddlers will cooperate in a primary care setting if their caregivers are not actively involved.

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

A child’s growth slows considerably after 12 months, with height and weight increasing in intermittent increments. Growth is about 3 in (7.7 cm) in length and 4 to 6 lb (1.8–2.7 kg) in weight per year, with most toddlers reaching an average height of 34 in (87 cm) and weight of 27 lb (12.3 kg) at 2 years. The toddler’s height at 2 years is about half expected adult height. During the second year, head circumference normally increases about 1 in (2.6 cm). Between ages 2 and 5 years, growth continues at about ½ in (1.3 cm) per year.

The toddler generally begins to walk by age 12 to 15 months, displaying the classic protruding abdomen and bowleggedness. The abdomen will protrude less as the abdominal muscles develop, and the bowleggedness will disappear as the weight of the trunk becomes more proportional to the rest of the body. Other major milestones to be achieved are running, speaking a vocabulary of at least 200 words by age 2 years, walking backwards, and hopping on one foot by age 3 years. Toddlers generally do not alternate feet when climbing stairs.

Because the toddler’s anatomy and physiology differ from those of the infant and adult, there are multiple normal variations of which the primary care provider should be aware for this age group. Some of these variations also require changes in examination technique.

Physical Development

Skin, Head, and Neck

There is a decrease in the proportion of subcutaneous fat during the second year. The posterior fontanelle should have closed at 2 months, with the anterior fontanelle closing by 2 years. Shoddy lymph nodes are normal, because they are more prominent than in adults.

Eyes

Permanent eye color usually is established by 1 year of age. A pink glow to the iris is indicative of albinism; black and white speckling is indicative of Down syndrome. Large spacing between the eyes may be normal but also may indicate a problem. Unfortunately, there is no accurate method to test visual acuity for the child younger than 3 years. The use of the red reflex and cover tests, however, may provide significant insights into possible visual deficits.

Ears

The auditory canal is directed upward, and the pinna should be pulled downward to aid visualization. The speculum should be inserted far enough so that the pneumatic otoscopy can be performed. After a child cries, a slight redness is normal as a result of increased vascularity. At a distance of 8 ft, the clinician should whisper a sound, command, or question appropriate to the child’s developmental level. An adherent lobule of skin may be a normal variation on the external ear.

Nose

A nasal speculum usually is not necessary. The examination may be done by pushing the tip of the nose upward with the thumb and visualizing with a light. Watery discharge is normal if the child has been crying. When examining, the provider should remember that paranasal sinuses are not well developed until late childhood.

Mouth and Oropharynx

A toddler’s crying is an opportunity to visualize the oral cavity. Tonsils are larger in children than adults, extending beyond the palatine arch until age 11 or 12 years. Foul odor in the mouth may indicate a foreign body in the nose. The tongue’s mobility should be noted; protrusion may indicate mental retardation, while shortening affects speech. Timing and sequence of tooth eruption are noted by the following formula:

Child’s age in months – 6 = number of teeth (up to age 2 years)

Thus, an 18-month-old toddler should have 12 teeth. By age 2½ years, 20 deciduous teeth should have erupted. If the child is cooperative, the examination may be done without a tongue blade.

Lungs

At this age, respiratory activity is abdominal; therefore, intercostal motion is abnormal. The toddler’s chest normally is more resonant than that of the adult, and breath sounds are louder due to the thinness of the chest wall. The child’s crying can be used as an opportunity to evaluate fremitus.

Heart

Up to age 7 years, the apical impulse often is visible and felt normally in the fourth intercostal space just to the left of the midclavicular line. Heart sounds are louder, with a higher pitch and shorter duration than adults. S1 is louder than S2 at the apex. Sinus arrhythmia occurs normally in many children, as do innocent murmurs, which must be distinguished from organic murmurs. More than 50% of children develop innocent murmurs during their childhood. Correct diagnosis of the murmur is important to rule out more serious heart disease. Innocent murmurs are usually systolic, of short duration, less than grade 3 intensity, and of a low-pitched, vibratory, musical quality. They often are poorly transmitted and are heard best with the bell along the left sternal border in the second or third interspaces, with the child lying supine (Bates, 1995). Murmurs vary in intensity and quality with position change. Innocent murmurs also are characterized by a physiologically split S2 (the split between A2 and P2 varying with inspiration and expiration).

Abdomen

Up to age 4 years, the abdomen is larger than the chest, making the toddler appear “potbellied” both when sitting and standing. Abdominal respirations are normal up to age 7 years; lack of abdominal movement is indicative of a problem. Umbilical hernias are common in children younger than 2 years and in older children of some ethnic groups. Most resolve without intervention by age 5 years. The liver edge is palpable 1 to 2 cm below the right costal margin. Visible peristaltic waves and aortic beat in the epigastric region may be normal for thin children but always warrant further evaluation. Abdominal skin should be used to test skin mobility and turgor. Tenderness during examination may be determined by noting the child’s expression or pitch of cry.

Rectum and Genitalia

Perianal skin tags are common in children. The clinician should observe for diaper rash. Forcible retraction of foreskin on an uncircumcised male should not be attempted. In females, vaginal and labial adhesions are noted, as is a pronounced clitoris. Parents should be reassured that such findings are normal and advised to diaper loosely to avoid irritation.

Musculoskeletal/Neurologic

Abduction of the forefoot distal to the metatarsal/tarsal line is common and usually corrects itself by 2 years. During infancy and young toddlerhood, many children appear “bowlegged.” As toddlerhood progresses, they change to a “knock knees” appearance. In toddlers, thoracic convexity is decreased, and lumbar concavity is increased. Muscle strength, motor coordination, cognitive-perceptual development, and cranial nerve function are tested predominantly through observation and must be in relation to norms for growth and development.

Psychosocial Development

Psychosocial development is a major accomplishment during the toddler years, with Erikson describing the psychosocial crisis as autonomy versus shame and doubt. The general theme is that of holding on and letting go, with the significant person being the male caretaker. Ideally, the toddler has developed a sense of trust, has decreasing dependency needs, and is ready to begin to master six major areas: individuation (differentiation of self from others); separation from caregivers; control of body functions; communication with words; acquisition of socially acceptable behavior; and egocentric interactions with others. While accomplishing these goals, the toddler develops a sense of control, increasing independence, and autonomy. If the toddler is kept dependent in areas he or she has begun to master, or if the toddler is made to feel inadequate when attempting new skills, the child may develop a sense of shame and doubt. During this time of extensive psychosocial development, the continued need for a security object (eg, blanket) is expected, especially during times of stress.

Freud describes the toddler conflict of holding on and letting go as the anal stage (age 8 months–4 years). The focus shifts from the mouth to the anal area, with emphasis on bowel control. The child experiences both frustration and satisfaction as he or she attempts to gain control over withholding and expelling. The conflict between holding on and letting go gradually resolves as toilet training progresses.

Socially, toddlers play parallel, meaning beside rather than with other children. Play is the major socializing medium, and inexpensive toys found in the home are often the most popular—pots and pans, pencil and paper, “helping” the caretaker. Toddlers frequently engage in what is called “negativism” as a way of asserting their opinion. They are trying to convey that they have thought about what they want and have a reason for their decisions but are sometimes unable to convey the thought process due to limited vocabulary. For this reason, discipline can seem like a battle of wills at times. Caretakers need to be reasonable but consistent with discipline, offering the toddler appropriate choices whenever possible.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

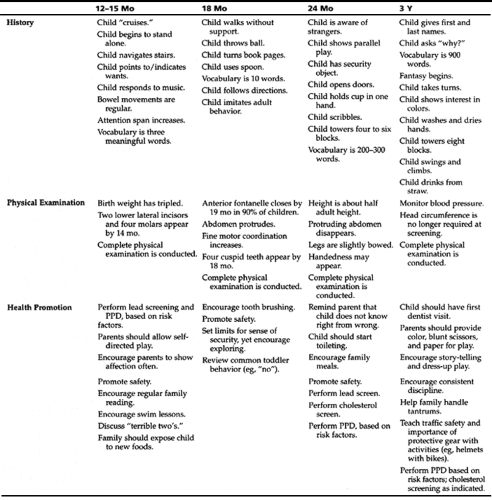

Table 9-1 presents critical foci for the toddler at different stages in the areas of history, physical examination, and health promotion. These guidelines can help providers as they conduct well child visits.

History

A caregiver with an ill toddler or multiple children in attendance may be unable to give a comprehensive history in the first visit. The history may be taken over several visits and entered together as a complete database, with the most important information pinpointed during the primary visit.

Topics

The following are topics to discuss during the history:

Informant: Who is giving the history?

Biographic data: Information should be briefly checked at every visit, especially when visits are 6 months apart. The child’s current nickname and best way to reach the caregiver during office hours should be included.

Chief complaint/reason for visit: For a well child visit, an open-ended question, such as “How have things been going?” is often very productive.

Present health status: Current developmental status is addressed under this heading. Gross motor development (walks alone, skips, climbs), fine motor development (stacks blocks, draws with crayon, buttons, uses scissors), language skills (uses multiple words, speaks in sentences, uses baby talk, has speech problems), and cognitive development (remembers solutions to simple problems, understands different points of view for conflicting problems) should all be listed, with examples of the child’s current level of mastery at home. Any such behaviors observed in the office setting also should be noted.

Family history: This section is important to update at every visit, because it may reveal stresses in the family/ home and other issues that may affect the child and caregiver.

Past health status: Building on the data collected during the infant’s first year, the clinician addresses the following at every visit:

Childhood illnesses: Include any recent exposures. What is the sickest the toddler has ever been? Include age and complications for chickenpox, rubella, measles, mumps, pertussis, strep throat, and frequent ear infections.

Serious or chronic illnesses: List age, when, and where treated and any complications for meningitis or encephalitis, seizure disorders, asthma, pneumonia or chronic lung problems, rheumatic fever, diabetes, kidney problems, sickle cell anemia, or allergies.

Serious accidents or injuries: Note age, extent of injury, when and how treated, and complications of head injuries, falls, auto accidents, burns, poisonings, fractures, traumas, and so forth.

Operations or hospitalizations: List what, where, when, why, by whom, complications, and the child’s reaction. (A child who had a particularly frightening past experience may need special preparation for the examination to follow.)

Current medications: List what, why, when, how much, and any problems for prescriptions, over-the-counter drugs, vitamins, any home remedies, or complementary approaches.

Allergies: Include any reactions to drugs, foods, contact agents, and environmental factors (eg, lead, second-hand smoke, wood stoves).

Health maintenance: Include the last examination (when, where, why, by whom, and outcome). Also include dental examinations and all screening tests.

Immunizations: Note ages administered and any reactions.

Developmental history: The child’s current developmental ability is recorded under “Present Health Status” (above). This section is a review of milestones and a general statement from the parents concerning this child’s development compared with siblings and whether parents think the growth and development have been normal. List the age that the child achieved any milestones since the last visit.

Nutrition: Include food preferences or dislikes, overall appetite, vitamins, where child eats and with whom, whether child feeds self, whether caregivers feel there are feeding issues, and the amount and type of junk food consumption. Ask caregivers to provide a 24-hour diet recall, including the size of servings and frequency of meals and snacks. Inquire about bottles at night left in the crib.

Psychosocial history: How is the family unit? Has it changed since the last visit? What is the toddler’s current security item (eg, toy, blanket)? Does the child display any repetitive behaviors? Who is the current primary caregiver? What are the current day care arrangements?

Activity: Describe the amount of active and quiet play, outdoor play, time spent watching television, and special hobbies or activities. List the amount of time spent reading per day. Is the child in day care or preschool? How many friends does the child have? Does the child show any problems with making friends?

Rest: List how long the child rests each day and night, where, and with whom. Note any nightmares or night terrors. Does the child sleep in a family bed? Does the child have any ritualistic nighttime behaviors? Is the child a sound sleeper, or does he or she awaken frequently?

Elimination: Include toilet teaching issues, ages of daytime bowel and bladder control, and nighttime bowel and bladder control. (Bowel and bladder control often are achieved separately, as are daytime and nighttime control.)

Stress management/coping skills: Have there been any recent changes or stresses? Has the child displayed recent changes in mood? Does the child have tantrums? If so, how often, and how does the caregiver respond?

Discipline: What method are caregivers currently using? Is it effective?

Environment: Are parents generally aware of the environment needed for a toddler to live safely? Include toys appropriate for age, car seats, stairs, yard equipment, protection from falling out of bed, poisons, description of neighborhood, and information on the family’s residence (heat, ventilation, hot water, window gates). Asses for lead risk.

Review of Systems

The following is a general review of systems to be conducted during the history taking:

General: frequency of colds, infections, illnesses, fevers, or sweats; presence of edema; or changes in affect, behavior, or energy

Allergy: asthma, eczema, hay fever, hives, sinus disorders, food or drug allergies, sneezing, conjunctivitis

Skin: birthmarks, pigment or color changes, mottling, change in mole, rashes, lesions, easy bruising, easy bleeding, texture change, sweating or dryness, infection, hair growth, itching, change in nails

Head: headache, head injury, dizziness

Eyes: discharge, redness, itching, photophobia, visual acuity (where does the child sit to watch videos?), redness, pain, edema, strabismus

Ears: earaches, infection, drainage, auditory acuity, cleaning

Nose and sinuses: frequency of colds and runny noses, stuffiness, infection, drainage, nosebleeds

Mouth and throat: general condition of teeth, hygiene, dental visits, sores in mouth or tongue, sore throat, difficulty swallowing or chewing, mouth breathing

Speech: change in voice, hoarseness, clarity, articulation, vocabulary

Neck: swollen or tender glands, limitation of movement, stiffness

Respiratory: difficulty breathing, chronic cough, shortness of breath, wheezing or noisy breathing, croup history

Cardiovascular: cyanosis, fainting, exercise intolerance (can child keep up with peers?), murmurs

Hematologic: lymph node swelling, excessive bleeding or easy bruising, pallor, anemia, past exposure to lead/chelation

Gastrointestinal: abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, history of ulcer, diarrhea, bowel habits/toilet training status, constipation or stool-holding problems, use of evacuation aids, rectal bleeding, stool color change, pinworms by history, perianal pruritus

Urinary: frequency of voiding, characteristics of urine, steadiness or force of stream, straining, unusual color or odor, previous urinary tract infection, urethral discharge

Genital: birth defects, discharges, odors, rashes, irritations, pruritus, screening for sexual abuse, note how sexuality is handled in the home, areas of parental concern

Musculoskeletal: sprains, fractures, joint pains or swelling, limitation of motion, twitching, cramping, pain, weakness, posture, gait ability

Neurologic: numbness and tingling, seizures (febrile versus afebrile), staring episodes, learning difficulties, coordination, balance, dominant hand, developmental problems, tic, tremors, tone changes

Endocrine: excessive hunger, thirst, or urination; abnormal hair distribution; intolerance to heat or cold; anorexia; sudden unexplained changes in weight

Physical Examination

Approach to Examination

The toddler is in Erikson’s stage of developing autonomy. Basic dependency on the caregiver conflicts with the need to be independent and to explore the world. The results often are attempts to assert control and displays of frustration. Toddlers may be difficult to examine. They will be this way with almost everyone—their behavior should not be taken personally. The toddler has a heightened awareness of new environments, fears invasive procedures, and dislikes being restrained. This combination frequently will lead the child to be frightened and to cling to the caregiver.

Preparation

Advising the caregiver to bring along a favorite toy or security object (eg, blanket, stuffed animal) may be helpful. Because the 2-year-old does not like having clothing removed, clothes should be taken off one piece at a time during the examination. The provider begins by greeting the caregiver and child by name, but focuses mainly on the caregiver, giving the toddler room to adjust gradually and become familiar from a safe distance. The provider slowly gives attention to the child, focusing first on an object (dress, toy, bow in hair), then on how “big” the child is. A toddler will become engaged when ready—smiling, eye contact, talking, or accepting an object offered.

Toddlers like to have a sense of control and like to assert their opinion, often in the form of “no.” Therefore, choices should be given, but only when any answer is acceptable. If asked, “May I listen to your tummy now?” the child may answer “No!” The clinician who does so anyway will lose the child’s trust. The clinician should either instruct in a firm, caring voice that it is time to lay down so he or she can listen to the child’s tummy, or ask “Would you like me to listen to your tummy first, or your heart?” Demonstrating all procedures on the caregiver may enhance cooperation. Praise should be repeated each time the child cooperates. Such an approach also provides role modeling for parents in how to engage their child’s cooperation.

Positioning

If appropriate, toddlers should be offered the choice of being examined on their caregivers’ laps or on the “special table.” Young children are often most receptive to an examination while sitting on their caregiver’s lap. During the part of the examination when they need to be supine, the provider should position the chair to be knee-to-knee with the caregiver. The child’s head is then placed in the caregiver’s lap, and the child’s legs in the provider’s lap. During parts of the examination where the child must be restrained for safety, the help of a cooperative parent may be vital.

Sequence

Gross and fine motor skills and gait should be observed during the history, when the toddler thinks the clinician is focusing on the caregiver. When finished with the history/observations, the clinician can begin with the “games.” To evaluate the heart properly, the clinician listens through 10 noncrying heartbeats. This should be planned at an appropriate time for the child. “Game playing” continues during the examination (eg, “I’m going to listen to your belly. Can I guess what you had for breakfast this morning?”). The most invasive examinations—ear, nose, and throat—are left for last. Cold stethoscopes and new equipment can be frightening, so all equipment is warmed. Children should be allowed to handle the equipment, and all equipment should be tried out on the caregiver first. Finally, many toddlers like to listen to their own hearts and “blow out” the otoscope light.