Headaches in the Emergency Room

Dominique Valade

INTRODUCTION

In emergency departments (7,8), the top priority is to establish a precise etiologic diagnosis and to classify the headache as a primary headache, a benign secondary headache, such as from influenza, or a secondary headache due to a serious condition, requiring further exploration or emergency treatment (meningeal hemorrhage, meningitis, intracranial hypertension) (2,6). The crucial part of this diagnostic step is the interview. This step, supplemented by the clinical examination, will determine the diagnosis and, ultimately, the course of treatment, which is usually conducted on an outpatient basis for primary headache. For benign secondary headache, further diagnosis may be necessary, but can be continued on an outpatient basis. Finally, emergency diagnosis and treatment in the hospital setting may be necessary for secondary headache with serious underlying causes.

The physician must also identify headaches occurring in patients already hospitalized for another reason. It is important to rule out any iatrogenic causes such as drug-induced headaches or headaches caused by hypotension of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), such as secondary to a persisting fistula.

Finally, some patients diagnosed with a primary headache may sometimes require hospitalization either because of an acute exacerbation of their primary headache in a particular psychologic context, or, especially, for detoxification for chronic daily headache associated with drug abuse.

STEPS IN THE INITIAL DIAGNOSIS OF A HEADACHE SEEN IN THE EMERGENCY ROOM

Obtaining a History of a Patient Who Presents With Headache

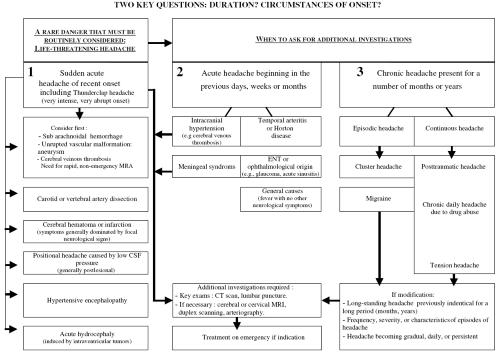

The first step in the diagnosis of headache is to obtain a history from the patient by interview. This can be difficult for a patient suffering from an intense headache, but can be manageable in a quiet, dark room. During the interview the physician should attempt to ascertain the duration since headache outset, the characteristics of the pain, and the circumstances of and symptoms associated with onset (Fig. 139-1).

Duration Since Onset and Evolutionary Profile

The following questions can assist the physician in classifying the headache:

How did the headache begin? (sudden or progressive onset)

How long have you had this headache? (acute or chronic headache)

Have you ever had this type of headache before? (unusual cephalgia or a new attack of a known headache pattern)

How has the pain changed since the onset of the headache? (spontaneous improvement, became worse, or remained the same)

Based on the answer to these questions, the headache can be classified as one of four types:

Sudden acute headache

Unusual new headache, beginning in the previous days, weeks, or months

Paroxysmal chronic headache (migraine, cluster headache)

Chronic tension-type headache or chronic secondary headache

The principal arguments for further diagnostic investigation are headache pain of recent onset, a new occurrence of fast or sudden onset, or, in a patient with a history of primary headache (migraine or tension headache), a pain that is totally different from the usual headache.

Characteristics of the Pain

The intensity of the pain does not give any indication for a diagnosis of primary or secondary headache. Nevertheless, any sudden and severe headache (thunderclap headache) must be regarded as secondary and further explored in the emergency department. It is important to consider the correlation between the intensity of the pain described by the patient and how the pain impacts his or her attitude (e.g., does he or she require bed rest, difficulties in expressing himself or herself). The type of pain can be very variable (pulsatile, continuous, “electric shock,” crushing, pressure, only discomfort) but may not be specific to a particular etiology. Topography can sometimes be an indication of a specific disease, such as the temporal pain of Horton’s disease, but is usually not specific to a particular etiology.

Circumstances of Onset

The circumstances surrounding the onset of a headache can sometimes guide the physician to an immediate diagnosis: cranial trauma (hemorrhage or cerebral contusion), medication or drugs recently taken, a lumbar puncture, recent peridural (epidural) or spinal anesthesia causing CSF hypotension, fever associated with general disease, etc.

However, the circumstances surrounding onset can also be misleading: An exertional headache can be benign but also a symptom of a meningeal hemorrhage, and a headache after lumbar puncture is generally a headache caused by hypotension of the CSF but can sometimes signal a cerebral venous thrombosis (1).

Medical History

A patient’s medical history must be obtained in a systematic way because it may qualify the diagnosis. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension (AVC), postpartum or venous thrombosis of the lower limbs, cerebral venous thrombosis, neoplasy (metastases), immunosuppressed patients with HIV (cerebral toxoplasmosis), anxiety and depression (decompensation with tension headache), and consumption of psychotropic drugs can all affect headache diagnosis.

Associated Symptoms

Any recent and unusual headache associated with a neurologic symptom, such as loss of consciousness, epileptic seizure, or focal signs, should always be assumed to be due to an intracranial lesion until proven otherwise. A headache with deterioration of health or claudication of the jaw in a patient of more than 60 years of age should immediately point to a possible diagnosis of Horton disease. On the other hand, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia are nonspecific symptoms associated with meningeal syndromes, such as intracranial hypertension, but are also associated with migraine. The absence of any associated symptoms does not eliminate a diagnosis of secondary headache and should not postpone the initiation of additional examinations if the headache is recent, unusual, and persistent.

Clinical Examination

In addition to a general examination including blood pressure and temperature, a clinical examination should include a neurologic and physical examination. Any abnormality in either the neurologic or physical examination indicates the need for further evaluation. On the other hand, a strictly normal clinical examination does not eliminate the possibility of a serious cause and should not preclude laboratory investigation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree