Headaches and Sleep

Poul Jennum

Teresa Paiva

Headache and sleeping problems are both some of the most commonly reported problems in clinical practice and cause considerable social and family problems, with important socioeconomic impacts. There is a clear association between headache and sleep disturbances, especially headaches occurring during the night or early morning. The prevalence of chronic morning headache (CMH) is 7.6%; CMH is more common in females and in subjects between 45 and 64 years of age; the most significant associated factors are anxiety, depressive disorders, insomnia, and dyssomnia (75).

However, the cause and effect of this relation are not clear. Patients with headache also report more daytime symptoms such as fatigue, tiredness, or sleepiness and sleep-related problems such as insomnia (77,52). Identification of sleep disorders in chronic headache patients is worthwhile because identification and treatment of sleep disorders among chronic headache patients may be followed by improvement of the headache.

FUNCTIONAL LINKS BETWEEN HEADACHE AND SLEEP

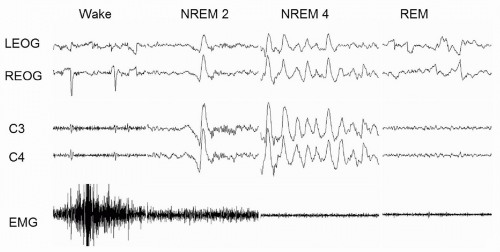

Sleep is organized with a recurrent alternation of two basic sleep stages: REM (rapid eye movement) and NREM (no rapid eye movement) sleep, intermixed with small amounts of the awake state/arousals (Fig. 134-1). Sleep serves a complex set of functions including tissue repair, anabolic hormones, thermoregulation, immune function, and synaptic reorganization and has significant influence on cognitive function, including maintenance of memory (58, 59, 60). Sleep deprivation or fragmentation induces sleepiness, fatigue and tiredness, headaches, anxiety, lack of concentration, confusion, perception disturbances, learning deficits, growth problems, increased health risks, and accidents (10,11,21,42,56,85,86,96). Sleep disorders may present as insomnias (with difficulties initiating or maintaining sleep), hypersomnias (with excessive daytime sleepiness), parasomnias (disorders of arousal, partial arousal, and sleep stage transition), or circadian disturbances.

Sleep is regulated by a complex set of mechanisms including the hypothalamus and brainstem and involving a large number of neurotransmitters including serotonin, adenosine, histamine, hypocretin, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), norepinephrine, and epinephrine (65). However, the specific roles in the relation between sleep and headache disorders are only partly known.

COMMON HEADACHE TYPES AND THE RELATION TO SLEEP

Commonly reported headache disorders that show relation to sleep are migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, and the very rare so-called hypnic headache.

Migraine

Potential relations between migraine and sleep have been established in several studies (1,14,16,18,47,66,83). Changes in the quality of sleep may occur up to 2 days before a migraine attack (94,95). The sleep pattern may be involved in the precipitation of migraine attacks, but the reports are conflicting. Overuse of medication may worsen the sleep pattern and headache. Withdrawal of the overused medication can alleviate the associated sleep disturbance along with the headache (41).

Outside of migraine attacks, sleep pattern and electromyographic (EMG) activity are normal, although the quantity of REM sleep and REM latencies were reported to be slightly increased in one study (30). Headaches and migraine with aura may be related to extended sleep duration (68). Apart from these findings, there is no evidence that sleep per se provokes migraine attacks.

Tension-Type Headache

Tension-type headache (TTH) is often associated with sleep disturbances such as insomnia, hypersomnia, and circadian disturbances. Drake et al.(31) studied sleep electroencephalogram (EEG), electro-oculogram (EOG), and EMG with a four-channel cassette EEG recorder in 10 common (without aura) migraine patients, 10 individuals with muscle contraction (tension-type) headache, and 10 chronic tension-vascular headache sufferers (pre-International Headache Society [IHS] classification). Migraine patients had essentially normal sleep, although REM sleep and REM latency were increased outside the attacks. Patients with TTH had reduced sleep time and sleep efficiency, decreased sleep latency but frequent awakenings, increased nocturnal movements, and marked reduction in slow wave sleep, without change in the amount of REM sleep. Mixed headaches with both tension and vascular features were also associated with reduced sleep, increased awakening, and diminished slow wave sleep. Furthermore, REM sleep amount and latency were reduced. The findings suggest that patients with intermittent migraine may have minimal sleep disturbance, while more chronic headache disorders may be associated with or worsened by poor sleep. The patient with TTH may have frequent awakenings and decreased slow wave sleep. The limitation of the study is that other causes of arousals and fragmented sleep were not determined (i.e., sleep apnea and periodic limb movements); furthermore, the headache disorders were not properly classified and the use of analgesic drugs was not evaluated. There is still need for more studies of the relation between TTH and sleep.

Cluster Headache

Cluster attacks may be provoked in the transition phase from REM to non-REM sleep (23,33,61,69,74,79,101). Because cluster headache (CH) occurs mainly during sleep and because oxygen supply is effective in the treatment of acute attacks, a potential relation between CH and sleep disordered breathing (SDB) has been hypothesized. Sleep apnea has been found in a number of CH patients (24,34,62). Small case series suggest that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment of sleep apnea in CH patients reduces CH severity (70,63). Sleep apnea probably does not cause CH, but may worsen CH attacks. Transient recurrent situational insomnia has been described in association with CH and diminished after the cluster period subsided (88,89). A single case report has described episodic CH in a patient with narcolepsy, but a causal relation is doubtful. Headache attacks are often related to REM sleep in episodic CH, but this relation is unclear in chronic CH (80).

Hypnic Headache

Headache attacks occur predominantly during nocturnal sleep, but may also occur during daytime naps. The mechanism is not known, but casuistic reports have suggested an association between arousal and headache episodes during SWS (5), REM sleep, or nocturnal desaturations (32,35,81). Alteration of unidentified biologic pacemakers has been suggested (78), whereas other studies have not identified any clear relation to sleep stages, time of the night, or any external factors. Changes in arterial blood pressure prior to nocturnal headache have been reported in few subjects (26). Whether this may represent presence of sleep apnea or changes in sympathetic outflow is not known.

SLEEP DISORDERS AND THEIR RELATION TO HEADACHE

Insomnia

Insomnia, defined by difficulties falling asleep and/or difficulties maintaining sleep, is a very common complaint,

mostly reported among females. An association between insomnia and other somatic and psychiatric complaints such as depression, anxiety, aches, and pain in muscles and joints and other daytime symptoms has been suggested. However, in other studies, such relation is not clear. In the U.S. national survey including 6072 adolescents, a clear relation between insomnia and headache was identified in less than 10% (87). The relation between insomnia and headache is probably complex. Insomnia may be caused by a variety of causes. For example, in children with primary chronic headache, sleep disorders such as insomnia and nocturnal awakenings, parasomnias (somnambulism, enuresis), and nocturnal snoring are commonly identified (27,93). In the elderly, chronic insomnia is often due to depression, SDB, periodic limb movements (PLMs), sleep apnea, and overuse of sleep and analgesic medication. In patients with chronic pain syndromes, such as primary fibromyalgia syndrome (PFS), an increased α:δ ratio suggests that increased arousability may be present (13,67,92), but care should be taken not to overemphasize these findings because the α:δ variant is unspecific and also present in other diseases and controls (64).

mostly reported among females. An association between insomnia and other somatic and psychiatric complaints such as depression, anxiety, aches, and pain in muscles and joints and other daytime symptoms has been suggested. However, in other studies, such relation is not clear. In the U.S. national survey including 6072 adolescents, a clear relation between insomnia and headache was identified in less than 10% (87). The relation between insomnia and headache is probably complex. Insomnia may be caused by a variety of causes. For example, in children with primary chronic headache, sleep disorders such as insomnia and nocturnal awakenings, parasomnias (somnambulism, enuresis), and nocturnal snoring are commonly identified (27,93). In the elderly, chronic insomnia is often due to depression, SDB, periodic limb movements (PLMs), sleep apnea, and overuse of sleep and analgesic medication. In patients with chronic pain syndromes, such as primary fibromyalgia syndrome (PFS), an increased α:δ ratio suggests that increased arousability may be present (13,67,92), but care should be taken not to overemphasize these findings because the α:δ variant is unspecific and also present in other diseases and controls (64).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree