Introduction

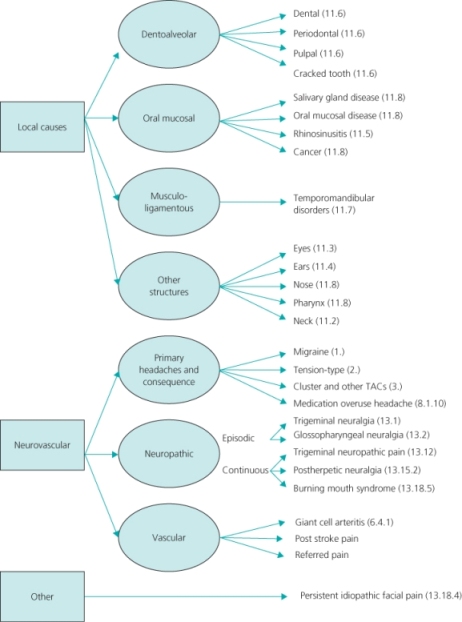

Headache and orofacial disorders comprise a heterogenous group of disorders of varying prevalence (Box 9.1). Despite being extremely common, headache and orofacial disorders are under-recognised and under-diagnosed and can result in considerable pain and disability. The second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II) lists more than100 headache and facial pain conditions (see Further reading). These can be further classified by cause (Figure 9.1). In this chapter, strategies for diagnosis are outlined and headache and facial pain that is often misdiagnosed or inadequately managed by non-specialists is the focus.

Figure 9.1 Classification of headache and orofacial pain (ICHD-II code). TACs: trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.

History

The history is a crucial step in diagnosis (Box 9.2). Patients often present with more than one type of pain, so a separate history is required for each. In the emergency setting, there may not be time to take a full history. The first task is to exclude conditions requiring more urgent intervention by eliciting any warning features (Table 9.1).

d. How long lasting?

Based on: MacGregor, EA, Steiner, TJ & Davies, PTG (2010) Guidelines for All Healthcare Professionals in the Diagnosis and Management of Migraine, Tension-Type, Cluster and Medication-Overuse Headache. Available at: http://www.bash.org.uk

Table 9.1 Warning features in the history

| Symptoms | Possible diagnosis | Investigation |

| Thunderclap headache (intense headache with abrupt or ‘explosive’ onset) | Subarachnoid haemorrhage | CT without contrast LP (if CT normal or unavailable) |

| Headache with atypical aura (duration >1 hour, or including motor weakness) | TIA Ischaemic stroke | CT with contrast/MRI |

| Fever | Meningitis | LP |

| Blood cultures | ||

| History of HIV or syphilis | Encephalopathy | Antibody testing |

| LP | ||

| MRI | ||

| History of cancer | Secondary brain metastases | CT with contrast/MRI |

| New onset headache over age 50 | Giant cell arteritis | ESR/CRP |

| Temporal artery biopsy | ||

| Glaucoma | Ophthalmological review | |

| Progressive headache worsening over weeks or months | Intracranial space-occupying lesion | CT with contrast/MRI |

Symptoms of raised intracranial pressure

Cognitive or personality changes Progressive neurological deficit

| ||

| Progressive sensory loss over the face and/or intraorally | Intracranial space-occupying lesion | Neurophysiological testing, CT or MRI |

aCT: computed tomography; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; LP: lumbar puncture; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; TIA: transient ischaemic attack

Examination

The examination will reflect the suspected diagnosis, particularly in the case of local disease of the oral cavity. A good light and expertise in examining the oral tissues is necessary. The head and neck should be carefully examined. Assess tenderness over the temporal arteries as well tenderness in the scalp, neck muscles and muscles of mastication. Examination of patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) involves the application of pressure to a variety of specific anatomical sites to see if they are tender (trigger points). The range of movements of the mandible is then evaluated in vertical opening, protrusive and lateral positions. A brief but thorough neurological examination, especially of the cranial nerves, should be undertaken, particularly if the diagnosis is uncertain or intracranial pathology is suspected. Fundoscopy is mandatory in all patients presenting with headache. Examination of the cranial nerves is particularly important for orofacial pain. General examination is indicated if headaches are considered secondary to systemic disease.

Investigations

There is no indication for investigations of primary headaches and they should be undertaken only if a secondary headache is suspected. If autoimmune disorders are suspected then blood tests may be indicated. Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) with axial and coronal sections is indicated for sinusitis, rhinogenic causes of pain or if malignancy is suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful to evaluate internal derangement in TMD. MRI and/or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can evaluate intracranial pathology. Special thin cut MRIs of the posterior fossa are needed to identify trigeminal nerve root compressions.

Management Issues

Patients’ beliefs are fundamental and must be clarified before treatment is initiated (Box 9.3). Severity of disease, impact on quality of life, insight and chronicity will impact on adherence to treatment as well as how the family views the condition (Box 9.4). The approach must, therefore, be a biopsychosocial one.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree