Headache

Fred Michael Cutrer

David F. Black

I have a pain upon my forehead here.

—William Shakespeare, 1564–1616, Othello, Act 3, Scene 3

Headache descriptions and treatments can be found in pre-Christian Sumerian and Egyptian writings. Aretaeus of Cappadocia in 2nd-century Turkey writes of people with headaches who “hid from the light and wished for death.” Headache is a common affliction; in 1985, a large-scale survey-based study in the United States reported that headaches occur in 78% of women and in 68% of men. It is estimated that 40% of adults in North America have experienced a severe, debilitating headache at least once in their lives.

Despite its long history and great prevalence in the population, the complaint of recurrent headache is still met with widespread

indifference and suspicion among many health care providers. As a result, the patient with headaches must often contend with haphazard and sometimes even inappropriate treatment. Such an attitude is unnecessary and can lead to tragic results because headaches not only can be the presenting symptom for a serious, even life-threatening abnormality, but also are liable to show a good response to therapy in most patients.

indifference and suspicion among many health care providers. As a result, the patient with headaches must often contend with haphazard and sometimes even inappropriate treatment. Such an attitude is unnecessary and can lead to tragic results because headaches not only can be the presenting symptom for a serious, even life-threatening abnormality, but also are liable to show a good response to therapy in most patients.

I. ANATOMY OF HEAD PAIN

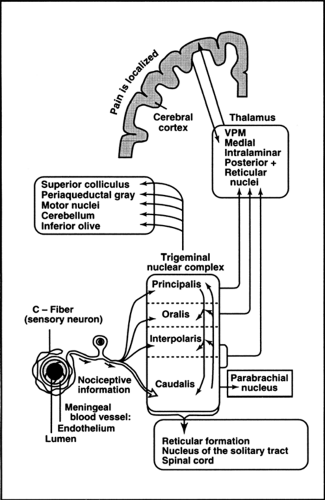

More than 50 years ago, epilepsy surgery performed on the brains of conscious patients under local anesthesia indicated that brain tissue itself was relatively insensate to electrical or mechanical stimulation, whereas electrical stimulation of the meninges or meningeal blood vessels produced a severe penetrating headache. The meninges and meningeal vessels are richly supplied with C-fibers (small fibers) and are the key structures involved in the generation of headache. The C-fibers from the meninges converge into the trigeminal nerve and project to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis in the lower medulla where they synapse. From the caudal brainstem, fibers carrying nociceptive signals project to more rostral trigeminal subnuclei and the thalamus (ventral posterior medial, medial, and intralaminar nuclei). Projections from the thalamus ascend to the cerebral cortex, where painful information is localized, and reaches consciousness (see Fig. 1).

II. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF HEADACHE

Head pain results from the activation of the pain fibers that innervate intracranial structures regardless of the activating stimulus. In a small number of patients, an identifiable structural or inflammatory source for the headache can be found using neuroimaging or other laboratory investigations. However, most patients encountered in clinical practice have primary headache disorders such as migraine or tension-type headache in which physical examinations and laboratory studies are unrevealing. Research into the pathophysiology of headache has been limited by the subjective nature of the complaints and the paucity of animal models with which to test hypotheses.

1. Genetic Underpinning of Primary Headache Disorders

It is becoming increasingly clear that primary headache disorders such as migraine are strongly influenced by heterogeneous genetic factors. Familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM), an uncommon autosomally dominant subtype, has been shown to occur because of defects within a single gene. In roughly 60% of families studied, the mutation is located on chromosome 19 and codes the α1 A subunit of a brain-specific P/Q type calcium channel. In another 20% of families, the mutation lies in a gene on chromosome 1 that encodes the α2 subunit of a Na+ K+ pump. Even within a rare subtype such as FHM, the genetic basis is complex, which predicts even greater heterogeneity for the more common forms such as migraine with and without aura. Several genetic linkage sites have been identified for these more common forms.

2. Traditional Theories of Migraine: Vasogenic versus Neurogenic

In the late 1930s, investigators proposed the vasogenic theory of migraine, which hypothesized that intracranial vasoconstriction was responsible for the aura of migraine and that

the headache resulted from rebound dilation and distention of cranial vessels. This theory was based on the observations that: (a) cranial vessels were important in the generation of headache; (b) extracranial vessels became distended and pulsated during a migraine attack in many patients; and, (c) vasoconstrictive substances such as ergots could abort the headache, whereas vasodilatory substances such as nitrates tended to provoke the headache. The competing neurogenic theory held that migraine was caused by a brain dysfunction. According to this hypothesis, when precipitating factors exceed cerebral threshold, a migraine attack occurred, and although vascular changes might occur during a migraine attack, they were the result rather than the cause of the attack. Proponents of the neurogenic theory pointed out that migraine aura symptoms could often not be explained on the basis of vasoconstriction within a single cerebrovascular distribution, and that prodromal symptoms such as euphoria, hunger, thirst or fluid retention that preceded headache in some by as much as 24 hours.

the headache resulted from rebound dilation and distention of cranial vessels. This theory was based on the observations that: (a) cranial vessels were important in the generation of headache; (b) extracranial vessels became distended and pulsated during a migraine attack in many patients; and, (c) vasoconstrictive substances such as ergots could abort the headache, whereas vasodilatory substances such as nitrates tended to provoke the headache. The competing neurogenic theory held that migraine was caused by a brain dysfunction. According to this hypothesis, when precipitating factors exceed cerebral threshold, a migraine attack occurred, and although vascular changes might occur during a migraine attack, they were the result rather than the cause of the attack. Proponents of the neurogenic theory pointed out that migraine aura symptoms could often not be explained on the basis of vasoconstriction within a single cerebrovascular distribution, and that prodromal symptoms such as euphoria, hunger, thirst or fluid retention that preceded headache in some by as much as 24 hours.

3. Sensitization within the Trigeminocervical Pain System

Because the duration of headache frequently exceeds the duration of the initiating stimulus, it is likely that sensitization within the trigeminal and upper cervical pain pathways contributes to the prolongation of headaches. Sensitizing events may occur in both the peripheral and central portions of these pathways.

Peripheral sensitization: There is increasing experimental evidence that, once activated, C-fibers release neuropeptides (i.e., substance P, neurokinin A, and calcitonin gene–related peptide) that generate a neurogenic inflammatory response within the meninges. This response consists of increased plasma leakage from meningeal vessels, vasodilation, and activation of mast cells and endothelial cells. Once set into motion, this process may act to lower the threshold of the C-fibers to further activation and, as a result, prolong and intensify the headache attack. Drugs known to be effective in ending a migraine attack such as dihydroergotamine (DHE) or sumatriptan have been shown to act at serotonin (5-HT) receptor subtypes to block the release of neuropeptides and the development of neurogenic inflammation.

Central Sensitization: Animal studies indicate that inflammatory or chemical C-activation results in expansion of receptive fields and recruitment of previously nonnociceptive neurons into the transmission of painful information. The changes are clinically reflected as hyperalgesia (lowered pain thresholds) and allodynia (the generation of a painful response by normally nonpainful stimuli). Analogous clinical phenomena are seen in headache disorders. For example, minor head movements, bending, or coughing, which normally do not cause pain, are perceived as painful during or in the hours following a migraine attack. Recent studies by Burstein et al. have demonstrated the stimulation of meningeal nociceptors, causes a lowering of the activation thresholds for convergent previously nonpainful skin stimulation. Subsequent studies of human subjects during migraine attacks have also demonstrated the development of cutaneous allodynia both within the areas innervated by the trigeminal nerve and in extratrigeminal areas.

III. CLINICAL APPROACH TO ACUTE HEADACHE

When faced with a patient in the emergency room (ER) whose primary complaint is that of a severe headache, the first question to ask is whether the headache is symptomatic of a potentially serious underlying abnormality requiring rapid and appropriate treatment. In most cases, the headache will represent a particularly severe episode in a primary headache disorder. However, the distinction between primary and secondary (symptomatic of another cause) headache must be made as rapidly and as accurately as possible. It is crucial to use the history and physical exam to decide whether the patient is at high or low risk, to order diagnostic tests, and to provide therapy accordingly. Laboratory tests and imaging studies ordered without good clinical indication are usually unhelpful and always expensive.

1. Important Questions to Ask

Is this headache the first of its kind? If the headache is unlike anything experienced previously, the risk increases. If it is similar (even if of greater intensity) to attacks experienced over many months or years, the likelihood that it is a benign process increases. This question becomes increasingly important for patients older than 40 years because the incidence of the first attack of migraine decreases and the incidence of neoplasm and other intracranial pathology increases after this age.

Was this headache of sudden onset? A persistent headache that begins and reaches its maximal intensity within a few seconds or minutes is more suggestive of an ominous vascular cause.

Has there been any alteration in mental status during the course of the headache? Generally, a family member or friend who has been with the patient must answer this question. Although patients with migraine can appear fatigued, especially after prolonged vomiting or analgesic use, obtundation and confusion are more suggestive of meningitis, encephalitis, or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Has there been recent or coexistent infectious disease? Infection in other locations (i.e., lungs, paranasal, or mastoid sinuses) may precede meningitis. Fever is not a feature of migraine or a primary headache disorder. Fever also may occur in association with subarachnoid hemorrhage, although this usually happens 3 to 4 days after the actual hemorrhage. Patients who are immunocompromised may exhibit fewer overt signs of infection initially.

Did the headache begin in the context of vigorous exercise or seemingly trivial head or neck trauma? Although effort induced migraine or coital migraine certainly exist, the rapid onset of headache with strenuous exercise, especially when minor trauma has occurred, increases the possibility of carotid artery dissection or intracranial hemorrhage.

Does the head pain tend to radiate posteriorly? Pain radiation between the shoulders or lower is not typical of migraine and may indicate meningeal irritation from subarachnoid blood or infection.

Other important points not to be overlooked in a careful history:

Do other family members have similar headaches? Migraine has a strong familial tendency.

What medications does the patient take? Certain medications can cause headache. Anticoagulants and oral antibiotics place the patient in a higher risk group for hemorrhage or partially treated central nervous system (CNS) infection.

Does the patient have any other chronic illness or a history of neurologic abnormality? These may confuse the neurologic examination.

Is the headache consistently in the same location or on the same side? Benign headache disorders tend to change sides and locations at least occasionally.

2. Important Physical Findings

It is crucial to examine each patient carefully, especially when there are atypical elements in the history. A basic neurologic examination should be performed that addresses the following six components.

Mental status: What is the patient’s level of consciousness? Is the patient able to maintain normal attention during the examination? Are language and memory normal?

Cranial nerves: Each cranial nerve should be tested separately. Are there asymmetries? Is there papilledema?

Motor: Are motor strength and muscle tone symmetrical and within the normal range? Are there any abnormal involuntary movements?

Sensory: Are there asymmetries of pain, temperature or proprioceptive sensation?

Coordination: Is there dysmetria or gait ataxia?

Reflexes: Is there asymmetry of reflexes in either the upper or lower extremities?

Three findings on examination should be considered as signs of possible serious pathology:

Nuchal rigidity: This can be an indicator of either meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Toxicity: Is there a low-grade fever or persistent tachycardia? Does the patient appear more acutely ill than most patients with migraine?

Previously unnoticed neurologic abnormality: Subtle findings such as a slight pupillary asymmetry, a unilateral pronator drift, or extensor plantar response are important and should lead to further investigation.

3. When to Order Laboratory Tests or Imaging Studies

Laboratory tests should be obtained to confirm the presence of abnormalities suspected from the history and physical examination and should be appropriate for the pathology suspected. Laboratory, electroencephalographic, or neuroimaging “fishing trips” are discouraged because they rarely provide useful information, can delay treatment, and can divert attention

away from more relevant findings. At present, the computerized tomography (CT) scan is the imaging study most likely to be available in the acute setting. There are three major indications for an urgent CT scan:

away from more relevant findings. At present, the computerized tomography (CT) scan is the imaging study most likely to be available in the acute setting. There are three major indications for an urgent CT scan:

The presence of papilledema

Any impairment of consciousness or orientation

The presence of localizing or lateralizing findings on neurologic examination

CT scanning is most useful for identifying recent intracerebral and extracerebral hemorrhages, hydrocephalus and brain abscesses, or other space-occupying lesions.

IV. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SECONDARY HEADACHES

Headache can be symptomatic of many underlying abnormalities. The relative frequency of secondary headaches is small when compared to that of primary headache disorders. However, it is vital that these headaches are diagnosed quickly and treated appropriately. The most common etiologies are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Secondary headache etiologies | |

|---|---|

|

V. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF PRIMARY HEADACHES

In clinical practice, most patients investigated because of head pain will ultimately prove to have a primary headache disorder (i.e., recurrent headaches for which no underlying structural, infectious, or other systemic abnormality can be found). Migraine and tension-type headaches are the most commonly diagnosed disorders in this population, but cluster headache and other less common syndromes are also occasionally seen. In order to classify and investigate primary headaches, the International Headache Society (IHS) has developed Classification and Diagnostic Criteria for Headache and Facial Pain. These criteria are invaluable for clinical research and are presented in Table 2 with the caveat that many patients do not fall neatly into a diagnostic category.

Table 2. Diagnostic criteria for common headache types | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||