In adults seen early after injury, cerebral blood flow (

CBF) is reduced and secondary insults such as hypotension and hypoxemia have devastating effect. Brain swelling and any accompanying intracranial hypertension can contribute to this early secondary ischemia. Problems in

CBF and metabolism are not exclusive to adults and are observed in infants and children. Infants with severe

TBI commonly have cerebral hypoperfusion, and a global

CBF of <20 mL/100 g/min was associated with poor outcome (

32). Following early posttraumatic hypoperfusion,

CBF may increase to levels

greater than metabolic demands, producing a state of relative hyperemia (

33). Alternatively, a phase of increased cerebral metabolism of glucose may accompany posttraumatic hypoperfusion. In adults, the use of monitoring techniques that reflect the coupling between

CBF and metabolism (e.g., using brain microdialysis and oxygen probes) is increasing, and the presence of key phenomena is influencing practice. In children, a recent report indicates a unique pattern of brain tissue oxygen tension with severe

TBI: the best threshold for favorable outcome was noted at a level of 30 mm Hg, and high, rather than low, values were observed in some patients with refractory intracranial hypertension and compromised cerebral perfusion, likely reflecting failed uptake rather than failed delivery (

34). Such impaired metabolism after severe

TBI in children was recently confirmed in an

MRI study of 17 children where the authors found variable

CBF after injury, but hypoperfusion and low oxygenation predominating (

35). Taken together, these findings are consistent with preclinical and adult clinical studies of brain metabolism suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction after

TBI.

Hypotension and hypoxemia are strongly associated with poor outcome; the focus should be on these targets in resuscitation.

Hypotension and hypoxemia are strongly associated with poor outcome; the focus should be on these targets in resuscitation. Hypoventilation due to lung or neurologic causes is common in traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury.

Hypoventilation due to lung or neurologic causes is common in traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury. The mechanism and pattern of head and brain injury will help to anticipate meningitis, carotid dissection, and hypopituitarism.

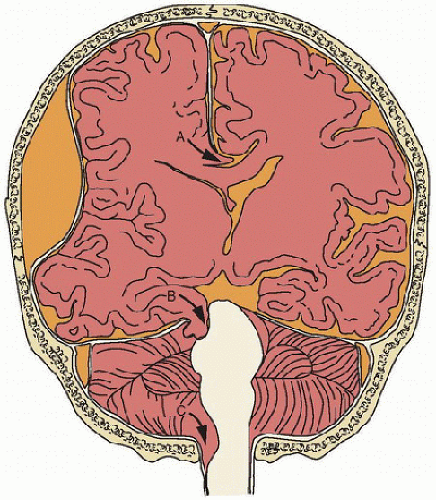

The mechanism and pattern of head and brain injury will help to anticipate meningitis, carotid dissection, and hypopituitarism. In general, head injuries conform to one of three types: blunt head injury, sharp head injury, or compression injury.

In general, head injuries conform to one of three types: blunt head injury, sharp head injury, or compression injury.