HAZARDOUS AQUATIC LIFE

In general, anyone who gets an infection following a wound acquired in a naturral aquatic environment should be treated with an antibiotic to cover Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species (use dicloxacillin, erythromycin, or cephalexin), and a second antibiotic to cover Vibrio or Aeromonas species (use ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline). An infection from Vibrio or Aeromonas bacteria is more likely in deep puncture wounds, if there is a retained spine (such as from a stingray), and in people who suffer from an impaired immune system (diabetes, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], cancer, chronic liver disease, alcoholism, chronic corticosteroid therapy).

SHARKS

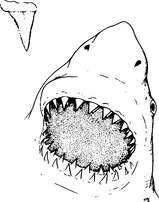

The jaws of the shark contain rows of razor-sharp teeth, which can bite down with extreme force (Figure 184). The result is a wound with loss of tissue that bleeds freely and can lead rapidly to shock (see page 60).

The basic management of a major bleeding wound is described on page 54. Even if a shark bite appears minor, the wound should be washed out and bandaged, and the victim taken to a doctor. Often, the wound will contain pieces of shark teeth, seaweed, or sand debris, which must be removed to avoid a nasty infection. Like other animal bites, shark bites should not be sewn or taped tightly shut, to allow drainage. This helps prevent serious infection. The victim should be started on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline).

The skin of many sharks is rough, like sandpaper, and can cause a bad scrape. If this occurs, it should be managed similar to a second-degree burn (see page 108).

Shark Avoidance

1. Avoid shark-infested waters, particularly at dusk and after dark. Do not dive in known shark feeding grounds.

2. Swim in groups. Sharks tend to attack single swimmers.

3. When diving, avoid deep drop-offs, murky water, or areas near sewage outlets.

4. Do not tether captured (speared, for example) fish to your body.

5. Do not corner or provoke sharks.

6. If a shark appears, leave the water with slow, purposeful movements. Do not panic or splash. If a shark approaches you while you are diving in deep water, attempt to position yourself so that you are protected from the rear. If a shark moves in, attempt to strike a firm blow to the snout.

7. If you are stranded at sea and a rescue helicopter arrives to extract you from the water, exit the water at the earliest opportunity.

BARRACUDAS

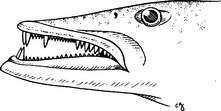

Barracudas may bite victims and create nasty wounds with their long canine-like teeth (Figure 185). These wounds are managed similar to shark bites (see above). Because barracudas seem to be attracted to shiny objects, the swimmer, boater, or diver is advised to not wear bright metallic objects, particularly not a barrette in the hair or anklet dangled on a leg near the surface from a boat or dock.

MORAY EELS

Although they look quite ferocious, moray eels (Figure 186) seldom attack humans, unless provoked. They have muscular jaws equipped with sharp fanglike teeth, which can inflict a vicious bite. A moray tends to bite and hold on; in some instances, it is necessary to break the eel’s jaws to get it to release.

A moray bite should be managed similar to a shark bite (see page 354). Even if the bite is very small, it should be examined by a physician, to be sure that all tooth fragments have been removed. If the bite is more than superficial and on the hand, on the foot, or near a joint, the victim should be started on an antibiotic (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline) to oppose Vibrio bacteria. Avoid sewing or otherwise tightly closing a moray bite unless absolutely necessary.

SPONGES

Sponges handled directly from the ocean can cause two types of skin reaction. The first is an allergic type similar to that caused by poison oak (see page 234), with the difference that the reaction generally occurs within an hour after the sponge is handled. The skin becomes red, with burning, itching, and occasional blistering. The second type of reaction is caused by small spicules of silica from the sponges that are broken off and embedded in the outermost layers of the skin. This causes irritation, redness, and swelling. When large skin areas are involved, the victim may complain of fever, chills, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, and muscle cramps.

1. Soak the affected skin with white vinegar (5% acetic acid) for 15 minutes. This may be done by wetting a gauze pad or cloth with vinegar and laying it on the skin.

2. Dry the skin, and then apply the sticky side of adhesive tape to the skin and peel it off. This will remove most sponge spicules that are present. An alternative is to apply a thin layer of rubber cement or a commercial facial peel, let it dry and adhere to the skin, and then peel it off.

3. Repeat the vinegar soak for 15 minutes or apply rubbing (isopropyl 40%) alcohol for 1 minute.

4. Dry the skin, and then apply hydrocortisone lotion (0.5% to 1%) thinly twice a day until the irritation is gone. Do not use topical steroids before decontaminating with vinegar; this might worsen the reaction.

5. If the rash worsens (blistering, increasing redness or pain, swollen lymph glands), this may indicate an infection, and the victim should be started on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline). If the rash is persistent but there is no sign of infection, a 7-day course of oral prednisone in a tapering dose (for a 150 lb, or 68 kg, person, begin with 70 mg and decrease by 10 mg per day) may be helpful. Corticosteroids should always be taken with the understanding that a rare side effect is serious deterioration of the head (“ball” of the ball-and-socket joint) of the femur, the long bone of the thigh.

JELLYFISH

The dreaded box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) (Figure 187) of northern Australia and the Indo-Pacific contains one of the most potent animal venoms known. A sting from one of these creatures can induce death in minutes from cessation of breathing, abnormal heart rhythms, and profound low blood pressure (shock). A sting from the Irukandji (Carukia barnesi) causes a syndrome of muscle spasm (back pain), sweating, nausea and vomiting, high blood pressure, and perhaps death.

Be prepared to treat an allergic reaction following a jellyfish sting! (See page 66.)

The following therapy is recommended for all unidentified jellyfish and other creatures with stinging cells, including the box jellyfish, Portuguese man-of-war (“bluebottle”) (Figure 188), Irukandji, fire coral (Figure 189), stinging hydroid, sea nettle, and sea anemone (Figure 190):

1. If the sting is thought to be from the box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri), immediately flood the wound with vinegar (5% acetic acid). Keep the victim as still as possible. Continually apply the vinegar until the victim can be brought to medical attention. If you are out at sea or on an isolated beach, allow the vinegar to soak the tentacles or stung skin for 10 minutes before you attempt to remove adherent tentacles or further treat the wound. In Australia, surf lifesavers (lifeguards) may carry antivenom, which is given as an intramuscular injection at the first-aid scene. The pressure immobilization technique is no longer recommended as a therapy for jellyfish stings.

2. For all other stings, if a topical decontaminant (vinegar or isopropyl [rubbing] alcohol) is available, pour it liberally over the skin or apply a soaked compress. (Some authorities advise against the use of alcohol on the theoretical grounds that it has not been proven beyond a doubt to help. However, many clinical observations support its use. Since not all jellyfish are identical, it is extremely helpful to know ahead of time what works for the stingers in your specific geographic location.) Vinegar may not work as well to treat sea bather’s eruption (see page 236); a better agent may be a solution of papain (such as unseasoned meat tenderizer—see below for precaution about duration of therapy). For a fire coral sting, citrus (e.g., fresh lime) juice that contains citric, malic, or tartaric acid may be effective. Topical lidocaine 4% may effectively numb a jellyfish sting, but may not lesson the envenomation.

Figure 188 Portuguese man-of-war (“bluebottle”), with a close-up of stinging cells located on the tentacles.

Until the decontaminant is available, you can rinse the skin with seawater. Do not rinse the skin gently with fresh water or apply ice directly to the skin, as these may worsen the envenomation. A brisk freshwater stream (forceful shower) may have sufficient force to physically remove the microscopic stinging cells, but nonforceful application is more likely to cause the cells to fire, increasing the envenomation. A nonmoist ice or cold pack may be useful to diminish pain, but take care to wipe away any surface moisture (condensation) before the application. Recent observations from Australia suggest that hot (nonscalding) water application or immersion may diminish the sting of the Portuguese man-of-war from that part of the world. The generalization of this observation to treatment of other jellyfishes, particularly in North America, should not automatically be assumed, because of the fact that application of fresh water worsens certain envenomations.

3. Apply soaks of vinegar or rubbing alcohol for 30 minutes or until pain is relieved. Baking soda powder or paste is recommended to detoxify the sting of certain sea nettles, such as the Chesapeake Bay sea nettle. If these decontaminants are not available, apply soaks of dilute (quarter-strength) household ammonia. A paste made from unseasoned meat tenderizer (do not exceed 15 minutes of application time, particularly not on the sensitive skin of small children) or papaya fruit may be helpful. These contain papain, which may also be quite useful to alleviate the sting from the thimble jellyfish that causes sea bather’s eruption (see page 236). Do not apply any organic solvent, such as kerosene, turpentine, or gasoline. While likely not harmful, urinating on a jellyfish, or any other marine, sting has never been proven to be effective.

4. After decontamination, apply a lather of shaving cream or soap and shave the affected area with a razor. In a pinch, you can use a paste of sand or mud in seawater and a clamshell.

5. Reapply the vinegar or rubbing alcohol soak for 15 minutes.

6. Apply a thin coating of hydrocortisone lotion (0.5% to 1%) twice a day. Anesthetic ointment (such as lidocaine hydrochloride 2.5% or a benzocaine-containing spray) may provide short-term pain relief.

7. If the victim has a large area involved (an entire arm or leg, face, or genitals), is very young or very old, or shows signs of generalized illness (nausea, vomiting, weakness, shortness of breath, chest pain, and the like), seek help from a doctor. If a child has placed tentacle fragments in his mouth, have him swish and spit whatever potable liquid is available. If there is already swelling in the mouth (muffled voice, difficulty swallowing, enlarged tongue and lips), do not give anything by mouth, protect the airway (see page 22), and rapidly transport the victim to a hospital.

To prevent jellyfish stings, an ocean bather or diver should wear, at a minimum, a synthetic nylon-rubber (Lycra [DuPont]) dive skin. Safe Sea Sunblock with Jellyfish Sting Protective Lotion (www.buysafesea.com), which is both a sunscreen and a jellyfish sting inhibitor, has been shown to be effective in preventing stings from many jellyfish species.

CORAL AND BARNACLE CUTS

1. Scrub the cut vigorously with soap and water, and then flush the wound with large amounts of water.

2. Flush the wound with a half-strength solution of hydrogen peroxide in water. Rinse again with water.

3. Apply a thin layer of bacitracin or mupirocin ointment, or mupirocin cream, and cover with a dry, sterile, nonadherent dressing. If no ointment or dressing is available, the wound can be left open. Thereafter, it should be cleaned and redressed twice a day.

4. If the wound shows signs of infection (extreme redness, pus, swollen lymph glands) within 24 to 48 hours after the injury, start the victim on an antibiotic to oppose Vibrio bacteria (e.g., ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline), as well as an antibiotic to oppose Staphylococcus bacteria (e.g., dicloxacillin or cephalexin).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree