The epidemiology of CPP in women is not well defined, as often the focus in the literature is on the disease process that may be associated with the pain directly, such as endometriosis. However, there are multiple prevalent studies on chronic pain from Europe and the United States of America, where the impact of reported pain on daily activities and function are reported [22]. Quite clearly, pain has a significant impact on the quality of life. It is within these publications that one has some idea of the prevalence of CPP. Some estimate it affects up to 30% of all women at any one time.

IASP were instrumental in developing a taxonomy for all chronic pain conditions. In so doing, it has brought clarity and order to a very complex world of mixed terminology often confusing diagnosis with symptoms and clinical states. Table 1 show the taxonomy adapted from IASP for gynaecological conditions.

The International Continence Society in 2011 formed a multi-disciplinary group to formulate a view on terminology used in CPP generally. This has helped start a dialogue on the global front to unify terms used and under what circumstances. This approach was applied to multiple other CPP conditions. No document has been published as yet, though the proceedings are available from the International Continence Society directly [14].

CPP is known to be a difficult condition to classify and contain, and unsurprisingly the pathological basis of the condition remains poorly understood. The basic premise remains that some sort of insult to a designated organ may have triggered an inflammatory response, which gradually led to widespread neurological sensitization in the organ and then globally spread to the rest of the pelvis. In essence, the pain is caused by an overwhelming sensory response, which clearly will have a centralized element to it. In the process the musculo-skeletal system becomes involved, as do other muscle groups resulting in a generalized ‘hyper-contractile’ state throughout the body, as seen in facial pain states [14], which further intensifies the pain making it difficult to control but also making it possibly amenable to non-pharmacological means of therapy, such as physiotherapy.

DESCRIBING THE SUBJECT

Aetiology of CPP in Women

The aetiology of CPP in women is multifactorial and often affects multiple systems. It is rare for only one organ system to be affected, as pain in one system such as the reproductive system often affects other systems in the pelvis, such as the lower urinary tract. The commonest well-defined causes of gynaecological pain include dysmenorrhoea, infection, endometriosis, adenomyosis, gynaecological malignancy, injuries related to childbirth and pain associated with pelvic organ prolapse and prolapse surgery, particularly where mesh is involved [22].

In cases where the pain is more diffuse, such as vaginal and vulvar pain syndromes, the origins can be many and include:

• History of sexual abuse

• History of chronic antibiotic use

• Hypersensitivity to yeast infections, allergies to chemicals or other substances

• Abnormal inflammatory response (genetic and non-genetic) to infection and trauma

• Nerve or muscle injury or irritation

• Hormonal changes

These aetiological factors can also apply to other pelvic conditions in women. Therapeutic options remain limited and require a multi-disciplinary pain management approach, with psychological and physiotherapy input.

The aetiology of CPP is shown in Table 2.

The commonest conditions encountered in gynaecology, as outlined above, tend to be recognised easily by many gynaecologists. However, the less commonly recognised conditions can be missed and patients can be told that ‘nothing untoward has been found’, which can be incredibly frustrating for the patient. It is important to raise awareness of these other conditions. Equally important is to recognise the gastrointestinal and urological associations, as they can be key to understanding the patient’s symptoms.

Aetiological Types of CPP in Women

Common Gynaecology CPP Conditions

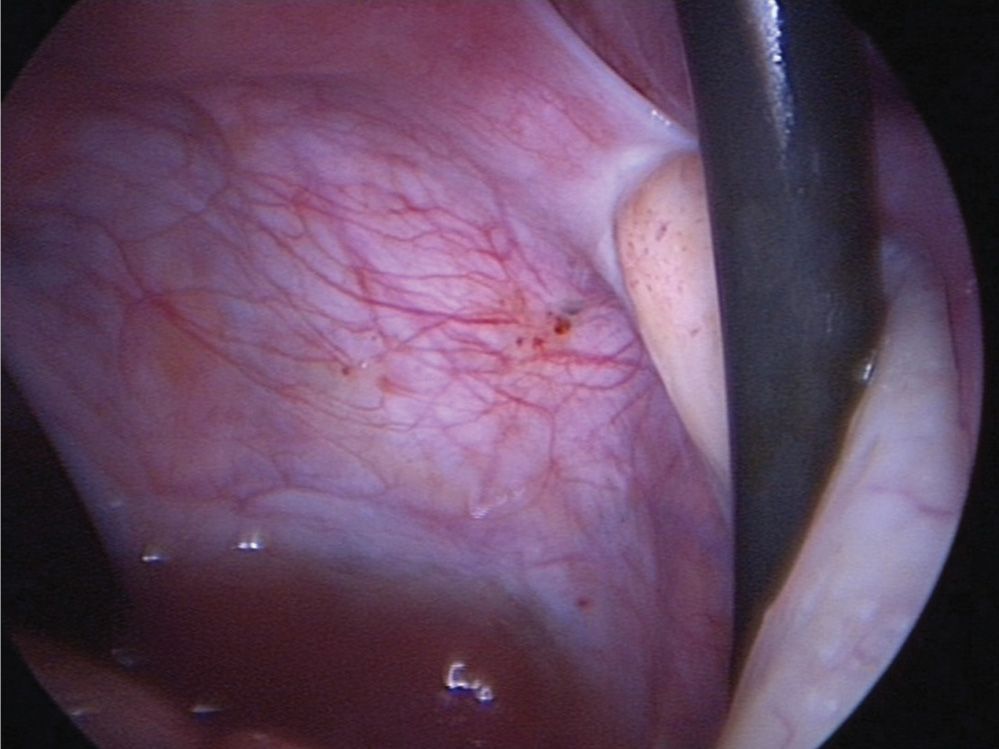

• Endometriosis lesions occur more frequently in CPP patients than controls. The endometriotic tissue can be found covering the entire peritoneal cavity and is often found directly on top of different abdominal and pelvic organs [28]. However, the symptoms do not correlate well with the extent of the pathology (Fig. 1). Patients may present with pain which is usually periodic and associated with menses (dysmenorrhea), intercourse (deep dyspareunia), passing urine or defecation [28], occasionally the pain is continuous and can have a huge impact on quality of life [20]. The definitive diagnosis is best made by laparoscopy [28]. Pain associated with endometriosis may be treated medically or surgically, currently there is a great push for extensive surgery to get rid of any active disease. However, despite extensive surgery and medical treatment, it has a recurrence rate of 50% in 5 years [30] (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2 Causes of Chronic Pelvic Pain (CPP)

Commonly recognised gynaecological causes of CPP | • Endometriosis • Dysmenorrhoea • Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease • Adhesions • Postpartum trauma • Perineal pain syndrome |

Less commonly recognised gynaecological causes of CPP | • Myofascial pain • Pelvic congestion/varicosity syndrome • Urogynaecology conditions, such as descending perineum syndrome • Post-surgical pain after gynaecology oncology or urogynaecology surgery |

Gastrointestinal/Urological associations | • Bladder pain syndrome (Interstitial cystitis) • Ano-rectal pain disorders • Irritable bowel syndrome |

FIGURE 1 Fine spots of endometriosis seen on the peritoneal surface of the pelvis in a patient being investigated for pain.

• Chronic Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID): Acute PID usually results from ascending infection [1]. Multiple partners and previous sexually transmitted disease are known risk factors. The scarring, inflammation and adhesions from acute PID is thought to cause chronic PID. The pain is usually intermittent with episodes being precipitated by intercourse, eating, defecation, or heavy activity. Many causative organisms have been identified, including – Chlamydia, Trachomatis, Neisseria Gonorrhoeae, gram negative bacilli, Haemophlus Influenzae, streptococci, mycoplasma and various anaerobes [18]. Though the investigation and treatment of acute PID is well covered in standard gynaecological texts, the treatment of chronic PID is not well determined and often unsatisfactory. A single course of broad spectrum antibiotics (e.g. Tetracycline or Doxycycline) may be beneficial, but many patients eventually undergo radical surgery whereby the uterus, tubes and ovaries, if they are involved, are all removed. Sadly, surgical management is usually unsuccessful. No direct correlation between physical findings and pain has been found.

• Adhesions: Commonly occur following surgery, but they may also occur as a part of the chronic PID or in their own right [27]. Much pain in gynaecology is attributed to adhesions, though it remains to be seen whether they are truly the cause of pain [21]. A specific pain syndrome associated with adhesions is seen when the adhesions trap the ovaries following hysterectomy (residual ovarian syndrome) or the ovarian remnants following a previous oophorectomy (ovarian remnant syndrome) [33]. Both of these syndromes cause pelvic pain often with deep dyspareunia and post coital ache. There is no correlation between pain and the density of adhesions, or indeed the localisation of the ovaries. Adhesions are usually treated by laparoscopic adhesiolysis and concomitant adhesion-prevention intra-abdominal fluids, but they often recur.

• Perineal Pain Syndrome: Perineal pain is perhaps the most complex of the chronic pelvic pain syndromes in women. The perineum overlies the pelvic outlet and is bound posteriorly by the coccyx and buttocks and anteriorly by the external genitalia in women. The perineum derives its nerve supply primarily from various branches of the pudendal nerve. It also receives some fibres from the anterior labial branches of the ilioinguinal, genital branch of the genitofemoral, perforating cutaneous and muscular branches of the S2,3,4 and anococcygeal nerves. The patient with CPP will often complain that clothing irritates her (possibly suggesting allodynia or allergy) or that the vulva is always moist and sensitive (infection or hyperhidrosis). The effect of the pain on micturition and sexual activity can also be reported. It is important to differentiate between pain only associated with sexual activity (dyspareunia) and pain associated with nonsexual touch, which, obviously, may affect sexual activity [2]. Previous operations, allergies, trauma, psychological issues and psychosocial circumstances must be evaluated.

A complete examination of the abdomen, female genital tract, musculo-skeletal system, and neurological system should be carefully carried out.

The causes of female perineal pain are summarised in Table 3 and discussed accordingly.

Less Common Causes of Gynaecological Pain

• Myofascial pain: This is the most common somatic diagnosis followed by atypical cyclic pain, gastrointestinal causes, urological causes and pelvic vascular congestion [9]. It is often caused by lower abdominal wall scars producing pelvic sensations. Nerve entrapment may also occur. Treatment includes local anaesthetic injections with or without steroid, pelvic floor physiotherapy and biofeedback [4,6]. However, as a cause of gynaecological pain it is often not recognised.

• Pelvic congestion/varicosity syndrome: Pelvic varicosities have been under investigation as a possible cause of CPP, but their role has never been proven [29]. The pain is said to be throbbing and burning in nature, but there is no definitive imaging or other investigative technique that has been used that has clarified what the pathognomonic anatomical findings are [3,7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree