Chapter 34 Geriatric care

The elderly come to emergency department for a wide variety of reasons. Their presentation will most commonly be due to an acute medical illness, but equally there will often not be an obvious ‘medical’ emergency, but simply a crisis. What the older patient in the emergency department needs, more than anything else, is for you to take a careful history, which includes speaking to family, carers, friends and local doctor. Always check that the patient’s own account of him/herself is accurate, by asking someone else who knows the patient (this will often save time, unnecessary investigations and costs). Always consider the possibility of underlying medical problems as the cause of the current presentation, especially when the initial triage suggests that the presenting problem is merely ‘social’. Often, the biggest dilemma is deciding whether or not the patient can safely be sent home (see the discharge checklist in Box 23.1, Chapter 23, ‘The ill patient’), especially for those patients with minor, undifferentiated illnesses or falls, whose initial investigations have not shown any significant abnormality. Mistakes are often made when these decisions are rushed and ill-informed, leading to poor outcomes for the patient, including readmission to hospital and increased morbidity and mortality.

The rapidly increasing population of older Australians is placing enormous pressures on all aspects of our healthcare system, especially emergency departments. Many changes in primary care and community care of the elderly have left patients and their carers with little option other than to call an ambulance in response to a crisis situation or illness. Numerous studies on the elderly in emergency departments have shown similar findings. Older persons come to hospital more often by ambulance, wait longer in the emergency department, have a much higher rate of admission to hospital, have increased mortality, undergo more investigations and cost more money to treat. They are at increased risk of further deterioration or readmission after discharge from the emergency department.

It should be assumed that the patient will not remember much of what he or she has been told during their visit to the emergency department. It is wise to take a paternalistic approach, similar to when dealing with paediatric patients, where extra time is spent explaining the medical issues to the patient’s family or carers. This is not meant to suggest that the majority of our older patients are mentally incompetent, but merely to stress the importance of good communication, especially in those situations where the older patient is dependent on a variety of coordinated community services to remain at home.

THE GERIATRIC SYNDROMES

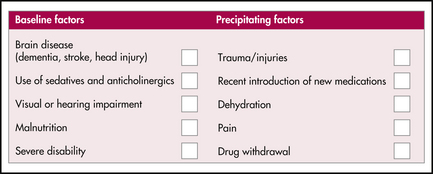

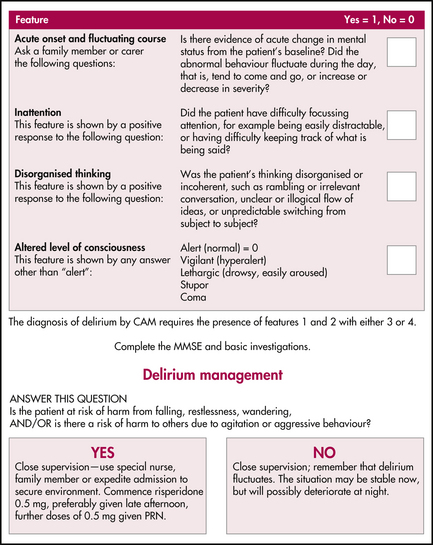

1 Acute confusion

Diagnosis