Genitourinary/Renal

10-1 Penile Fracture

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

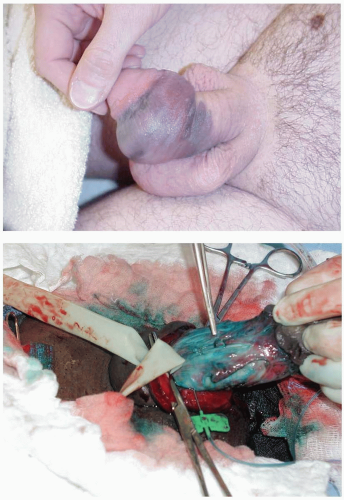

Penile fracture is rupture of the tunica albuginea that results from a rapid, blunt force to an erect penis. This force is usually a bending or impaction motion induced by vaginal intercourse or aggressive masturbation. Patients give a history of a “popping” or “cracking” sound followed by pain and rapid detumescence.1 On physical examination, the penile shaft is ecchymotic and swollen, with deviation most often away from the side of injury. This is often referred to as the “eggplant” deformity or “aubergine sign.” The fracture site may be directly palpable where the hematoma forms; this is referred to as the “rolling sign.” Most often the fracture is proximal and ventral in coital injuries. The incidence of penile fracture is relatively rare, but it is thought to be underreported.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is largely clinical, but it may be aided by cavernosography, urethrography, ultrasonography, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).1 Retrograde urethrography is necessary in all patients who are unable to void, in those with blood at the urethral meatus, and in those with frank hematuria.

Clinical Complications

The rate of complications with conservative management in some series has been as high 40%, compared with 11% among operatively treated patients.2 The most common complications are unacceptable penile curvature, painful erections, penile abscess formation secondary to missed urethral injuries, and late penile plaque formation akin to Peyronie’s disease.2 Less frequently, impotence, penile aneurysm, skin necrosis, fistulas, and high-flow priapism occur as a result of this injury.

Management

Penile fracture requires immediate urologic consultation for urgent surgical repair. This treatment includes evacuation of hematoma and suture repair of the ruptured tunica albuginea. The urethra is most often stented with the catheter to aid in restoration of anatomy and maintenance of the repair. Antiandrogens such as diethylstilbestrol, amyl nitrate, and benzodiazepines are used to prevent erection during convalescence. Some authors advocate conservative management consisting of Foley catheterization, penile splinting and pressure dressings, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), fibrinolytics, and antibiotics. This is recommended only in milder cases with normal findings on cavernosography.2

REFERENCES

1. Beysel M, Tekin A, Gurdal M, Yucebas E, Sengor F. Evaluation and treatment of penile fractures: accuracy of clinical diagnosis and the value of corpus cavernosography. Urology 2002;60:492-496.

2. Eke N. Fracture of the penis. Br J Surg 2002;89:555-565.

10-2 Penile Amputation

Colleen Campbell

Pathophysiology

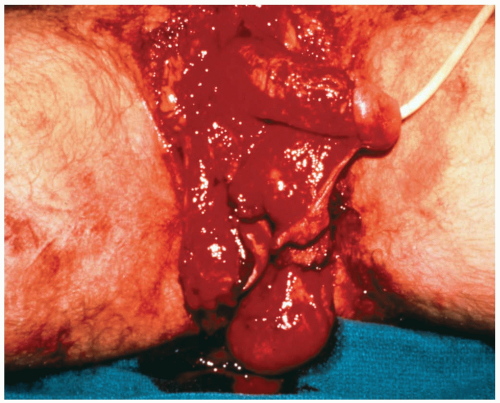

Penile amputation is an uncommon traumatic injury.1 Automutilation has been reported in psychotic (schizophrenic) men with sexual fears and in intoxicated men.2 Traumatic amputations may result from industrial or motor vehicle accidents.1 Circumcision performed by laypersons may result in accidental amputation.1,2,3

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of penile amputation is based on history and physical examination. Retrograde urethrography is useful in evaluating the extent of urethral injury. A complete blood count (CBC) and a basic chemistry panel are useful in the evaluation of the hypovolemia and acidosis that occur in association with amputation.1,2,3

Clinical Complications

Amputation of the penis has devastating social and physical ramifications for the patient. Urethral strictures and voiding problems are common. Loss of sexual function and necrosis occur. Replantation complications include skin loss, fistula formation, urethral contracture or stricture, necrosis, and loss of sensation and sexual function.1,3 These complications are significantly reduced with the use of microsurgical anastomosis of the dorsal penile artery and vein, as well as nerves.

Management

Penile amputations are often associated with other injuries, making a secondary survey and workup of associated injuries or drug overdose mandatory. Treatment of hypovolemia and shock are the primary goals, because substantial bleeding is possible. Emergency suprapubic catheterization is necessary if the urethra is involved. The amputated penis should be wrapped in a moist, saline-soaked, sterile dressing and placed in a plastic bag. Cooling should be maintained by placing the plastic bag in ice water slush. Care should be taken to avoid cold injury by avoiding direct penile contact with ice. Tetanus prophylaxis and antibiotics covering skin and urethral flora should be initiated in the emergency department (ED). Emergency referral to a urology specialist is indicated in any penile amputation case. Viable reconstruction has been initiated as late as 16 hours after the amputation.1 The treatment of choice for proximal amputation is microvascular replantation and repair of the dorsal artery, vein, and nerve.1,2,3

REFERENCES

1. Jezior JR, Brady JD, Schlossberg SM. Management of penile amputation injuries. World J Surg 2001;25:1602-1609.

2. Ignajatovic I, Potic B, Paunkovic L, Ravangard Y. Automutilation of the penis performed by the kitchen knife. Int Urol Nephrol 2002;34:113-115.

3. Darewicz B, Galek L, Darewicz J, Kudelski J, Malczyk E. Successful microsurgical replantation of an amputated penis. Int Urol Nephrol 2001;33:385-386.

10-3 Male Genital Degloving Injury

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Mechanical injury involving farm workers is the mechanism of injury in most cases of MGDI. The redundant skin of the scrotum and penis are entrapped when a pants leg becomes entangled in a piece of moving machinery with rotating parts. Finical and Arnold1 pointed out that the penile and scrotal skin is often avulsed in one piece, leaving a proximally based flap, and that the “loose skin of the penis usually tears behind the coronal sulcus, leaving the glans intact and pulling the skin off the penis down to the base.”

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually apparent on physical examination; however, these injuries cannot be fully assessed unless the patient is completely unclothed.

Clinical Complications

Complications include chronic genital deformity with the potential for permanent urologic dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, or both, as well as concomitant posttraumatic stress disorder.

Management

Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols should be adhered to, and the injured areas should be covered with sterile dressings soaked in sterile saline solution. Immediate on-site consultation with urology and/or plastic surgery specialists should be obtained. There should be no hesitation to transfer hemodynamically stable patients in order to obtain maximally experienced plastic surgical and urologic treatment. Prevention is the optimum treatment for these injuries.1,2,3

REFERENCES

1. Finical SJ, Arnold PG. Care of the degloved penis and scrotum: a 25-year experience. Plastic Recon Surg 1999;104:2074-2078.

2. Georgiou P, Liakopoulos P, Gamatasi E, Komninakis E. Degloving injury of the penis from pig bite. Plastic Recon Surg 2001;108:805-806.

3. Gencosmanoglu R, Bilkay U, Alper M, Gurler T, Cagdas A. Late results of split-grafted penoscrotal avulsion injuries. J Trauma 1995;39:1201-1203.

10-4 Penetrating Genital Trauma (Male)

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

Penetrating penile injuries are uncommon. Only 5% of all urologic injuries occurring during the Vietnam War were penile injuries.1 Patients often present with signs and symptoms of hypovolemia. After proper attention to the standard ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation), secondary survey of the trauma victim (after mandatory removal of all clothing) reveals the injury. Blood at the urethral meatus indicates a urethral injury. Bruising or swelling of the scrotum may be present with associated testicular injury. Careful examination of all related areas, including the abdomen, thighs, and rectum, is necessary to identify otherwise occult entry or exit wounds.

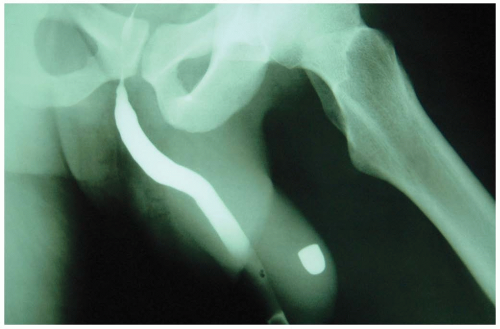

Diagnosis

The history and physical examination are the mainstays of diagnosis. Further evaluation includes retrograde urethrography to evaluate the extent of urethral injury. In one series, urethral damage was found in 22% of patients who sustained penetrating penile trauma.2 Blast effect alone can cause testicular injury.2 Testicular ultrasonography or nuclear scanning is necessary in patients with a suspected testicular injury. In one series, 72% of patients with penetrating trauma to the genitourinary tract had associated injuries, most commonly to the thigh.2 Evaluation of the abdomen and extremities is necessary, because major vascular injury is commonly associated with gunshot wounds to this region. Plain radiography, computed tomography (CT), and angiography are often necessary to rule out such injuries. Proctoscopy may also be used to evaluate associated rectal injury.

Clinical Complications

Hypovolemia and shock are the most life-threatening complications associated with genital gunshot wounds. Infection is the most common complication. Gangrene, urethral stricture, and fistula formation may result after penile gunshot wounds. Penile shortening, buildup of granulation tissue, and sexual dysfunction have also been documented.3

Management

Emergency urology and trauma team referral are warranted as soon as the injury is discovered. Tetanus and antibiotic prophylaxis should be initiated in the emergency department (ED). Skin and urethral flora should be covered as usual, with a cephalosporin or quinolone. Operative irrigation and débridement of the wounds may be necessary, especially if secondary missiles (e.g., clothing particles) are suspected to remain in the wound.2 Primary closure or reconstructive repair is performed at the discretion of the urologist.

REFERENCES

1. Cline KJ, Mata JA, Venable DD, Eastham JA. Penetrating trauma to the male external genitalia. J Trauma 1998;44:492-494.

2. Mydlo JH, Harris CF, Brown JG. Blunt, penetrating, and ischemic injuries to the penis. J Urol 2002;168:1433-1435.

3. Selikowitz, SM. Penetrating high velocity genitourinary injuries: statistics, mechanisms, and renal wounds. Urology 1977;9:371-376.

10-5 Scrotal Hematoma

Timothy Lum

Clinical Presentation

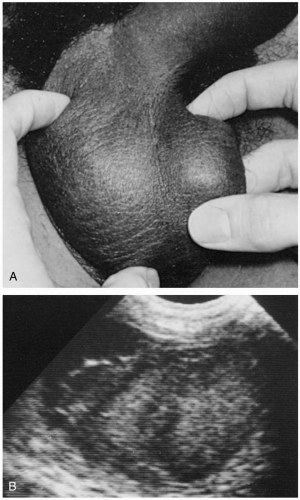

Patients with scrotal hematoma (SH) present after blunt or penetrating trauma to the lower torso or genitalia.1 If the SH is secondary to a pelvic fracture, the patient may also have blood at the urethral meatus and a high-riding, boggy prostate with or without pelvic instability.1

Pathophysiology

SHs can arise by many mechanisms. They may occur after direct genital trauma, or they may be the result of a pelvic fracture, with blood tracking downward through the fascial planes and settling in the scrotum. Some of these pelvic fractures may be associated with urethral disruption. If the SH is caused by direct scrotal trauma, testicular rupture should be a concern. Urologic procedures such as orchiectomy or hydrocelectomy can also lead to SH formation. Large volumes of blood can accumulate in the scrotum because of the distensibility of the scrotal skin, which has little to no ability to tamponade bleeding.2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SH can be made based on history and physical examination. Scrotal examination reveals an erythematous, edematous scrotum with blood discoloring the scrotal wall.1,2 However, pelvic radiography, urinalysis, and ultrasonography of the testicles with color flow Doppler are helpful to rule out concomitant injuries.2

Clinical Complications

Management

Advanced trauma life support (ATLS) protocols should be followed until the patient is stabilized. Urology consultation and possible surgical exploration are mandated if the scrotal injury is associated with a significant hematocele, gross hematuria, blood at the urethral meatus, testicular hematoma, or testicular rupture.1,2 SHs, especially those that develop postoperatively, may require drainage by a urologist and further exposure of the scrotal contents.2 A drain may be inserted, and the patient is administered antibiotics until it is removed.1 SHs or injuries not resulting in testicular hematoma or rupture can be treated with ice to reduce swelling and control pain, elevation to promote venolymphatic drainage, and oral analgesics.2

REFERENCES

1. Dreitlein DA, Suner S, Basler J. Genitourinary trauma. Emerg Medicine Clin North Am 2001;19:569-590.

2. Edelsberg JS, Surh YS. The acute scrotum. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1988;6:521-546.

10-6 Penile Zipper Injury

Christian M. Sloane

Clinical Presentation

The patient with penile zipper injury presents guarding the affected area and is usually anxious and in pain. There may be little or copious amounts of bleeding. The age group most commonly affected is 2 to 6 years. The tissue may be caught in one of two ways—in the movable zipper part itself, or between the teeth of the zipper.1

Pathophysiology

Typically, the loose skin of the foreskin or volar aspect of the penis becomes entrapped. This can occur during either closure or opening of the zipper; there is no clear predominance of either mechanism.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is straightforward and is made by visual inspection.

Clinical Complications

Injury to the urethra is possible if a significant laceration is present, and a urologic evaluation is warranted. Infection and hemorrhage are possible.

Management

For tissue caught in the teeth of the zipper, cutting transversely beneath the location of entrapment and pulling the teeth apart usually releases the area. For tissue caught in the moving part of the zipper, release can be more difficult, and anesthesia or sedation may be necessary. Gentle manipulation of the zipper after anesthesia and the addition of mineral oil are the simplest treatments and are often successful. If not, cutting the median bar (diamond or bridge) of the zipper in half will cause the interlocking teeth of the zipper to fall apart, freeing the skin. A bone cutter or wire clippers may be required to break the bar.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Wyatt JP, Scobie WG. The management of penile zip entrapment in children. Injury 1994;25:59-60.

2. Lundquist ST, Stack LB. Diseases of the foreskin, penis and urethra. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2001;19:529-546.

10-7 Constricting Penile Ring

David Flores

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

The presentation of a patient with a constricting penile ring is usually obvious upon physical examination. Patients may give a history of preceding use of a vacuum suction device. The penis appears engorged, may have purple discoloration, and may be cool to the touch. Priapism is evident.

Pathophysiology

Penile rings are constrictive bands that are placed around the shaft of the penis to maintain erection or to prevent premature ejaculation. The penile ring was first described in the Far East. A myriad of devices have been used, including bullrings, wedding rings, hammerheads, plumbing devices, and marketed products such as Electro-flex rings® and the Stormy Leather® penis ring.1,2 Patients often present after trying to use a constricting penile ring in conjunction with a vacuum device to achieve a more satisfactory erection. Once the venous flow is constricted, the penis remains erect. Ensuing edema may then cause the ring to become entrapped onto the penis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a constricting penile ring is based on the history and physical examination.

Clinical Complications

Patients frequently complain of painful ejaculations while the ring is in place. Priapism can lead to fibrosis and permanent cell death within 6 hours. Neurovascular damage can also occur as a result of the constricting force of the ring. Petechiae may develop at the ring site. Penile tip necrosis or permanent erectile dysfunction may result. Peyronie’s disease can also result from chronic use of penile rings in conjunction with vacuum erection devices.1,2

Management

Removal of the constricting device is necessary as quickly as possible to prevent irreversible neurovascular damage. Devices that are useful to this end include metal ring cutters and metal saws. The string method, in which umbilical tape is placed under the ring and the penis is wrapped distally, after which the proximal portion of the umbilical ring is gradually pulled, has been successful at times.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Levine LA, Dimitriou RJ. Vacuum constriction and external erection devices in erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am 2001;28:335-341.

2. Perabo FGE, Steiner G, Albers P, Muller SC. Treatment of penile strangulation caused by constricting devices. Urology 2002;59:137.

10-8 Priapism

Colleen Campbell

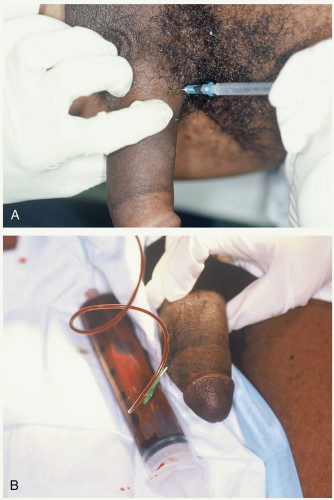

Clinical Presentation

Patients with priapism present with a painful erection. Patients may present after trauma with a painless erection resulting from an arterial high-flow state caused by injury to the cavernosal artery.

Pathophysiology

Priapism is the prolonged engorgement of the penis not related to sexual desire or stimulation. Most cases of priapism are caused by a low-flow state. The most common causes are sickle cell disease, drug-induced priapism, and malignancy-associated priapism. Sickled red blood cells (RBCs) may gather in sinusoidal spaces during physiologic erection, resulting in subsequent priapism; this is the most common type of priapism in children.1 Local injection of papaverine, crack cocaine use, and ingestion of sildenafil, trazodone, or chlorpromazine have all been associated with increased incidence of priapism.1 High-flow priapism is less acute in onset and results in fewer complications. It occurs when arterial inflow exceeds the capacity of the venous system, and it usually is painless. Most commonly, it is caused by trauma to the perineum in a straddle mechanism of injury.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is mostly clinical by history and physical examination. An intracavernous blood gas analysis may be obtained to differentiate high-flow priapism from low-flow or ischemic priapism. Penile technetium scans may also be used to assess blood flow states. On physical examination, the entire corpora cavernosa (or, rarely, only a segment of the cavernosa) is engorged.2 The corpus spongiosum usually is not involved.

Clinical Complications

Erectile dysfunction is common after priapism and can be expected in as many as 70% of cases treated conservatively.2

Management

Pain relief is essential in the treatment of priapism. Algorithms for treatment start with less invasive measures, followed quickly by more invasive treatments. In patients with sickle cell disease, hydration and red blood cells (RBCs) exchange transfusions have been attempted without conclusive differences in outcome.1 Hydroxyurea (a DNA synthesis inhibitor), hydralazine, and etilefrine (an α-adrenergic agonist) have also been used for their vasodilatory properties in the prevention of sickle cell-induced priapism.1 Intracavernous injection of an α-agonist (phenylephrine, ephedrine, epinephrine) may be effective if priapism is treated within the first 12 hours after onset. A trial of corporal irrigation may be attempted for 20 minutes, before proceeding to a surgical shunt procedure. An intracavernous pressure monitor reading indicating pressure less than 40 mm Hg indicates successful treatment.3

REFERENCES

1. Powars DR, Johnson CS. Priapism. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 1996;10:1363-1372.

2. Pautler SE, Brock GB. Priapism: from Priapus to the present time. Urol Clin North Am 2001;28:391-403.

3. Hatzichristou D, Salpiggidis G, Hatzimouratidis R, et al. Management strategy for arterial priapism: therapeutic dilemmas. J Urol 2002;168:2074-2077.

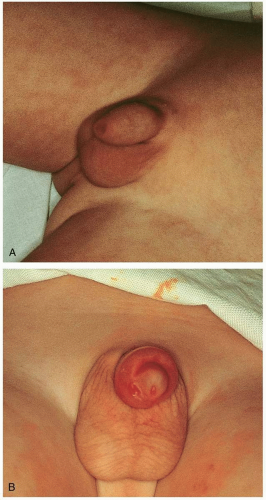

10-9 Phimosis

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

Phimosis occurs only in uncircumcised males. Physiologic phimosis occurs in all newborn males, because epithelial adhesion attaches the prepuce to the glans at birth.1 By 5 years of age, 90% of boys are able to retract the foreskin.1 Patients with phimosis are unable to retract the foreskin over the glans and may also present with symptoms and signs of balanoposthitis, urinary retention, or dyspareunia.

Pathophysiology

Clinical Complications

Management

Temporary treatment includes application of nonsteroidal creams or steroidal creams to reduce inflammation. The distal foreskin may be opened with the use of a hemostat to dilate the stenotic meatus. Dorsal slit incision of the prepuce or circumcision constitutes definitive therapy.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Lundquist, ST, Stack LB. Diseases of the foreskin, penis and urethra. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2001;19:529-546.

2. Atilla MK, Dundaroz R, et al. A nonsurgical approach to the treatment of phimosis: local nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory ointment application. J Urol 1997;158:196-197(abst).

10-10 Balanitis

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

Balanitis is more common in uncircumcised diabetic men and in male children.1 The patient may present with itching, swelling, or penile discomfort. The glans and foreskin may be erythematous, swollen, and malodorous. Discharge may be visible at the sulcus of the glans and prepuce. If a discharge from the urethra is present, a different diagnosis should be sought, because the urethra should not be involved in balanitis.

Pathophysiology

Balanitis is inflammation of the glans penis. Balanoposthitis involves inflammation of the prepuce as well. Balanitis may be caused by an acute or chronic infection or irritation of the glans. Poor personal hygiene is a major contributing factor. The most common infectious organisms are candidal species.2 Other infectious causes are anaerobic bacteria including group B streptococci, Gardnerella, and sexually transmitted infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV), human papillomavirus (HPV), syphilis, trichomoniasis, and amoebiasis. Noninfectious causes include local friction, irritation, or trauma; contact dermatitis, and dermatologic disorders such as psoriasis, lichen planus, and erythema multiforme exudativum.1

Clinical Complications

Complications are rare. However, chronic balanoposthitis may develop in those patients with continued poor hygiene, especially if the patient is a diabetic. This can eventually lead to phimosis or paraphimosis.

Management

Frequent cleansing with a mild soap, followed by adequate drying, is the mainstay of treatment. Candidal infections are treated with antifungal creams such as nystatin or clotrimazole. Anaerobic infections, Gardnerella, and Trichomonas should be treated with oral metronidazole. If a specific bacterial or viral source is found, appropriate oral antibiotics or antiviral agents should be initiated. If the infection is refractory to medical treatment, referral to a urologist for biopsy is indicated.

REFERENCES

1. Waugh, MA. Sexually transmitted diseases: balanitis. Dermatol Clin 1998;16:757-762.

2. Lundquist ST, Stack LB. Genitourinary emergencies: diseases of the foreskin, penis, and urethra. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2001;19:529-546.

10-11 Pearly Penile Papules

Zachary R. McDonald

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

Patients with pearly penile papules (PPPs) usually present concerned that they may have genital warts, because these entities are often mistaken for one another.

Pathophysiology

PPPs are benign, dome-shaped, asymptomatic angiofibromas that occur circumferentially around the coronal sulcus of the penis. The estimated incidence of PPP is 8% to 30%. The majority of cases occur in uncircumcised men, with all races being equally susceptible.1 PPP are not related to human papillomavirus (HPV) and are different in their arrangement in rows and their singular dome shape.1 Warts are not as linear or as clearly defined, and they usually form in clusters on the skin. Although the exact cause of PPP is unknown, uncircumcised men develop the papules more frequently than do those who are circumcised.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on clinical history and physical examination. Patients have pale/white or skin-colored, 1- to 2-mm dome-shaped spots that typically are located in rows around the corona and sulcus of the glans penis. To confirm the presence of PPPs and to rule out other potentially serious diseases such as carcinoma, it may be necessary to obtain a tissue diagnosis via biopsy. Microscopic examination reveals a number of thin-walled, ectatic vessels in the dermis, as well as fibroblastic proliferation. Papule cells may appear either starshaped or multinucleated.

Clinical Complications

PPP can cause a substantial amount of anxiety in patients, unless appropriate reassurance is forthcoming. Infection may be a complication if patients pick at or manipulate the lesions.

Management

Because of the harmless nature of PPP, most patients do not elect complex treatment. However, if patients insist on lesion removal, several modalities may be used, including podophyllin application, circumcision, electrodesiccation and curettage, cryotherapy, and carbon dioxide laser.2

REFERENCES

1. Hogewoning CJ, Bleeker MC, van den Brule AJ, et al. Pearly penile papules: still no reason for uneasiness. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:50-54.

2. Lane JE, Peterson CM, Ratz JL. Treatment of pearly penile papules with CO2 laser. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:617-618.

10-12 Testicular Torsion

Colleen Campbell

Clinical Presentation

Testicular torsion (TT) manifests as the sudden onset of unilateral, nonpositional testicular pain and tenderness. This may occur during athletic events or during sleep. Often, patients describe a history of previous episodes of similar symptoms lasting for short periods. Nausea and vomiting are present in 50% of cases.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree