CHAPTER 6 General

Anaesthesia for the Elderly

Physiology

GI

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes

Therefore, ↓ VD for water-soluble drugs, ↑ VD for fat-soluble drugs.

Specific drugs

Barbiturates. Larger VD with prolonged clearance; 30–40% ↓ dose requirement.

Benzodiazepines (Table 6.1). Increased CNS sensitivity. High protein binding of diazepam results in greater free drug in elderly in contrast to lesser change in dose requirements of midazolam. The latter may cause severe hypotension in the elderly (Committee on Safety of Medicines warning).

Table 6.1 Half-life of benzodiazepines

| t1/2 (h) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Young adult | Elderly | |

| Diazepam | 24 | 72 |

| Midazolam | 2.8 | 4.3 |

Opioids (Table 6.2). Smaller VD with higher initial plasma concentrations. Increased elimination half-life (↓ clearance greater than ↓ VD). Decreased protein binding of pethidine with increasing age.

Table 6.2 Half-life of opioids

| t1/2 β (min) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Young adult | Elderly | |

| Alfentanil | 90 | 130 |

| Fentanyl | 250 | 925 |

General principles of anaesthetic management

Anaesthesia and Perioperative Care of the Elderly

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2001

Summary

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Anaesthesia and peri-operative care of the elderly, 2001. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Dodds C., Murray D. Pre-operative assessment of the elderly. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:181-184.

Rivera R., Antognini J.F. Perioperative drug therapy in elderly patients. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1176-1181.

Anaphylactic Reactions

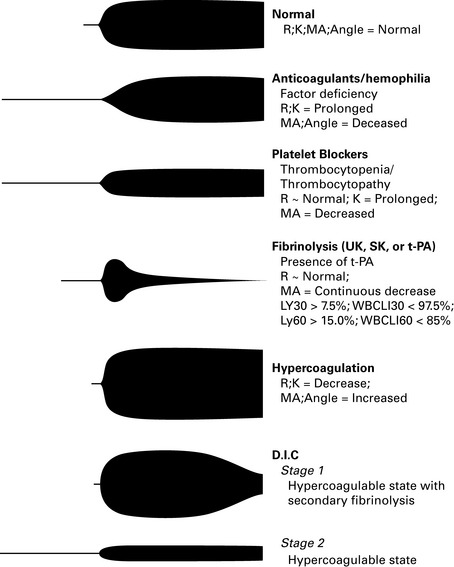

Hypersensitivity to drugs (Fig. 6.1)

In a French study (Laxenaire 2001), overall incidence of reactions was 1 in 13 000 anaesthetics, while the incidence of anaphylaxis to neuromuscular blocking agents was 1 in 6500 anaesthetics. Causes included neuromuscular blocking drugs (62%), latex (17%), antibiotics (8%), hypnotics (5%), colloids (3%) and opioids (3%).

Figure 6.1 Causes of life-threatening allergic reactions during anaesthesia.

(Data from Laxenaire 2001.)

Opioids

Usually cause anaphylactoid reactions. Mostly morphine. Reactions to synthetic opioids are rare.

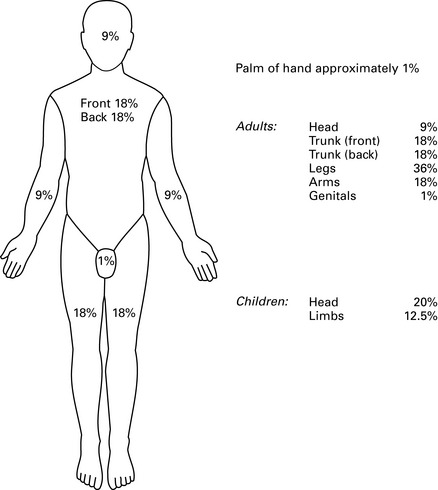

Clinical symptoms (Fig. 6.2)

Figure 6.2 The first clinical feature of an anaphylactic reaction.

(Data from Whittington and Fisher 1998.)

CVS. Arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension

Respiratory. Pharyngeal and laryngeal oedema (24%), rhinitis, pulmonary oedema

GI. Nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal colic

Other. Generalized oedema (7%).

Treatment

Suspected Anaphylactic Reactions Associated With Anaesthesia

Treatment

Immediate management

Investigations

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Revised guidelines (4E), Suspected anaphylactic reactions associated with anaesthesia, 2009. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Fischer S.S.F. Anaphylaxis in anaesthesia and critical care. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;20:136-139.

Hepner D.L., Castells M.C. Latex allergy: an update. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1219-1229.

Laxenaire M.C., Mertes P.M., Groupe d’Etudes des Réactions Anaphylactoïdes Peranesthésiques. Anaphylaxis during anaesthesia. Results of a two-year survey in France. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:549-554.

Romano A., Pascal D. Recent advances in the diagnosis of drug allergy. Curr Opin Int Med. 2007;6:443-447.

Whittington T., Fisher M.M. Balliere’s clinical anesthesiology, vol 12. Elsevier, London, 1998;301-321.

Wildsmith J.A.W., McKinnon R.P. Histaminoid reactions in anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:217-228.

Blood

Blood donors

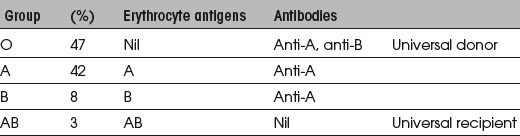

Blood groups

The ABO blood groups are summarized in Table 6.3.

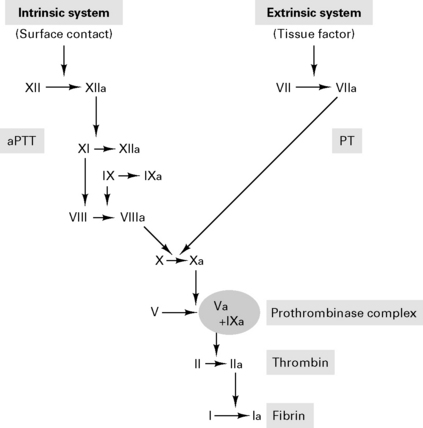

Coagulation cascade

Products

Whole blood

Platelet concentrates: 260 000 units used p.a. in the UK

Recombinant blood products

Recombinant FVIIa

rFVIIa initially developed to treat bleeding in haemophiliacs. FVIIa binds to tissue factor on damaged vascular beds to activate FIX and FX. The subsequent conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, activates platelets FVIII, FV and FXI and results in a large thrombin burst to transform fibrinogen to fibrin (Fig. 6.3). A recent meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials showed a reduction in blood transfusion requirements with no major safety concern (Ranucci 2008). Concerns remain regarding possible risks of thrombotic events.

Transfusion reactions

Acute

Delayed

Massive blood transfusion

Blood groups for urgent transfusion are:

Blood transfusions can be avoided by:

Guidelines for Autologous Blood Transfusion

British Committee for Standards in Haematology Blood Transfusion Task Force 1997

Intraoperative cell salvage

Indications. Elective and emergency surgery with expected blood loss >20% total body volume.

Contraindications. Bacterial contamination of wound, malignant disease and sickle cell disease.

Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Red Cell Transfusion

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, June 2008

Summary

Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Blood Component Therapy

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, December 2005

Recommendations

Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Intraoperative Cell Salvage

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, September 2009

Recommendations

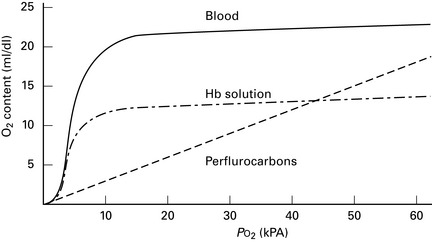

Artificial blood (Fig. 6.4)

Perfluorocarbons. Inert carbon chains with oxygen solubility 20 times that of plasma. One study showing that perfluorocarbon emulsion may limit transfusion requirements, but trend towards greater morbidity and mortality (Spahn et al 2005).

Postoperative care

Management of Anaesthesia for Jehovah’s Witnesses

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2005 (2E)

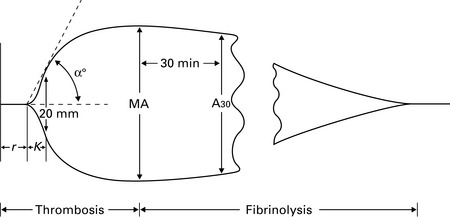

Consumptive coagulopathies

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Management of anaesthesia for Jehovah’s Witnesses, 2nd ed. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2005.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Blood Transfusion and the Anaesthetist – Red Cell Transfusion, 2008. June Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Blood Transfusion and the anaesthetist – blood component therapy, 2005. Dec Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Blood Transfusion and the anaesthetist – introperative cell salvage, 2009. Sept Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Bux J. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): a serious adverse event of blood transfusion. Vox Sang. 2005;89:1-10.

Contreras M., editor. ABC of Transfusion, ed 3, London: BMJ Publishing, 1998.

Mackman N. The role of tissue factor and factor VIIa in hemostasis. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1447-1452.

Martlew V.J. Peri-operative management of patients with coagulation disorders. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:446-455.

Maxwell M.J., Wilson M.J.A. Complications of blood transfusion. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:225-229.

Milligan L.J., Bellamy M.C. Anaesthesia and critical care of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2004;4:35-39.

Napier J.A., Bruce M., Chapman J., British Committee for Standards in Haematology Blood Transfusion Task Force: Autologous Transfusion Working Party. Guidelines for autologous transfusion. II. Perioperative haemodilution and cell salvage. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:768-771.

Ramanarayanan J., Krishnan G.S., Hernandez-Ilizaliturri F.J. www.emedicine.com/med/topic3493.htm, 2008. Factor VII

Ridley S., Taylor B., Gunning K. Medical management of bleeding in critically ill patients. 2007;7:116-121.

Serious Hazards of Transfusion Annual Report. www.shot-uk.org, 2008.

Shore-Lesserson L. Evidence based coagulation monitors: heparin monitoring, thromboelastography, and platelet function (Review). Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;9:41-52.

Silverman T.A., Weiskopf R.B. Planning Committee and the Speakers: Hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers: current status and future directions. Anaesthesiology. 2009;111:946-963.

Spahn D.R., Tucci M.A., Makris M. Is recombinant FVIIa the magic bullet in the treatment of major bleeding? Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:553-555.

Spahn D.R., Rossaint R. Coagulopathy and blood component transfusion in trauma. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:130-139.

Tanaka K.A., Key N.S., Levy J.H. Blood coagulation: hemostasis and thrombin regulation. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1433-1446.

Burns

Epidemiology

Systemic effects of burns

Tissue damage is due to both direct thermal injury and secondary damage from inflammatory mediators.

CNS. Encephalopathy, seizures.

Haematology. Bone marrow suppression, anaemia, thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy.

Skin. Increased heat, fluid and electrolyte loss. Loss of protective antimicrobial barrier.

Inhaled carbon monoxide and cyanide reduce tissue oxygen delivery.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes

Treatment of burn injury

Breathing

Carbon monoxide poisoning. 1000 deaths p.a. in the UK. The symptoms of CO poisoning are given in Table 6.4. HbCO results in over reading of the pulse oximeter. The half-life of carbon monoxide (250 times the affinity of O2 for Hb) is:

Table 6.4 Symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning

| %HbCO | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 0–10 | None |

| 10–20 | Headache, malaise |

| 30–40 | Nausea and vomiting, slowing of mental activity |

| >60–70 | CVS collapse, death. Consider hyperbaric O2 therapy |

Circulation

Blood loss during surgical debridement may be rapid and exceed 2 mL/kg per 1% of burn desloughed.

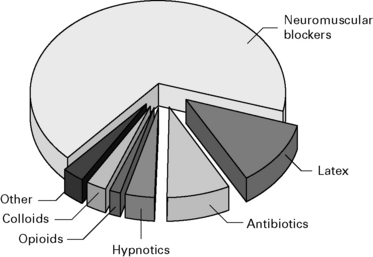

Extent and depth of burn

Burn size. This is estimated using the ‘Rule of Nines’ (Fig. 6.7).

Black R.G., Kinsella J. Anaesthetic management of burns patients. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:177-180.

Brazeal B.A., Traber D.L. Pathophysiology of inhalation injury. Curr Opin Anaesth. 1997;10:65-67.

Hilton P., Hepp M. The immediate care of the burned patient. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:113-116.

Latenser B.A. Critical care of the burn patient: the first 48 hours. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2819-2826.

MacLennan N., Heimbach D.M., Cullen B.F. Anesthesia for major thermal injury. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:749-770.

Pitkin A., Davied N. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. BJA CEPD Rev. 2001;1:150-157.