Gastrointestinal

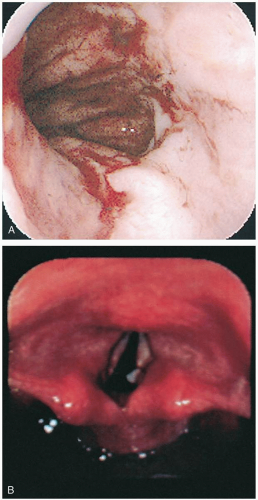

9-1 Thermal Esophageal Injury

Michael Greenberg

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

In some reports, histologic examination of the mucosa of the esophagus was “characterized by superficial mummified layers of necrotic anucleated nonviable squamous epithelium firmly adherent to the viable underlying squamous epithelial cells.”1 This is consistent with TEI resulting from direct contact with hot fluid to the mucosa.

Diagnosis

Clinical Complications

Complications include esophageal perforation, esophagitis, infection, and stricture formation.3

Management

Concomitant disease must be ruled out, especially in patients who complain of chest pain. Referral for immediate endoscopy is essential if TEI is suspected. Steroid administration and prophylactic antibiotics are controversial and should be considered in consultation with the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) surgeon who will be caring for the patient.

REFERENCES

1. Dutta SK, Chung KY, Bhagavan BS. Thermal injury of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1998;339:480-481.

2. Cohen ME, Kegel JE. Candy cocaine esophagus. Chest 2002;121:1701-1703.

3. Javors BR, Panzer DE, Goldman IS. Acute thermal injury of the esophagus. Dysphagia 1996;11:72-74.

9-2 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Derek Halvorson

Clinical Presentation

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) manifests as “heartburn”; patients describe a burning sensation in the epigastrium and lower substernal chest region. The sensation may progress into the throat or radiate into the back. Patients may complain of a sour taste in the mouth, persistent cough, wheezing, or hoarseness. Less commonly, patients may report dysphagia or a foreign body (FB) sensation in the throat. Symptoms may be more common at night (while lying supine) or after eating, especially after a large meal.1

Pathophysiology

GERD is a condition in which gastric acid secretion irritates and inflames the esophagus due to backward flow of gastric content.1 GERD is caused by the movement of gastric contents cephalad, into the esophagus, as a result of transient laxity of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Symptoms may be precipitated by exercise, bending forward, lying down, or ingestion of certain foods (peppermint, alcohol, onions, or fat).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by recognition of the typical history and elimination of more serious causes of the symptomatology. A 2-week treatment trial with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) may provide symptomatic relief and sensitivity and specificity equivalent to the more invasive gold standard, esophageal monitoring.1

Management

The treatment for GERD requires long-term modification of lifestyle and other medication interventions. Patients should be instructed to avoid large meals and not to lie down for 3 to 4 hours after eating. Patients should avoid caffeinated beverages, peppermint, fatty foods, onions, chocolate, spicy foods, citrus foods, alcohol, and tomatobased products. Lifestyle changes include discontinuation of smoking, weight loss, and elevation for the head of the bed. If there is no concern for other possible causes or complications (perforation, gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, ulceration, or cardiac, pulmonary, or vascular symptoms), the patient can be referred to a primary care physician for follow-up and consideration for further testing such as a 24-hour pH monitoring, endoscopy, or motility studies as needed.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Dent J, Jones R, Kahrilas P, Talley NJ. Management of gastrooesophageal reflux disease in general practice. BMJ 2001;322:344-347.

2. DeVault KR, Castell DO. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:1434-1442.

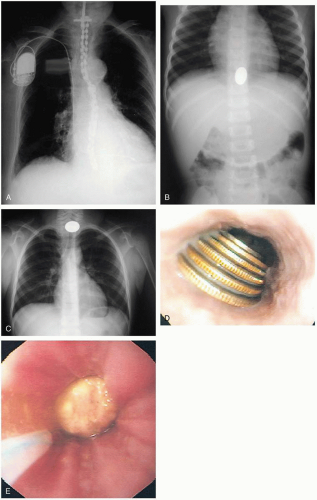

9-3 Esophageal Foreign Body

Derek Halvorson

Clinical Presentation

Most esophageal foreign bodies (FBs) occur in children younger than 4 years of age. Children may ingest a variety of small objects.1 Prisoners and psychiatric patients may ingest potentially harmful objects for a variety of reasons. In adults, the most commonly seen esophageal FBs are food-related boluses that are accidentally or purposefully ingested.

Children with a history of FB ingestions may be brought to the emergency department (ED) by a parent or a sibling, and they are often asymptomatic (7% to 35%).2 Adults more commonly have symptoms on presentation, and they often report anorexia, salivation, chest pain, dysphagia, or vomiting. Other complaints may include wheezing (often new-onset), persistent cough, stridor, choking, and recurrent pneumonia.

Pathophysiology

Esophogeal foreign body ingestions are found at one of three anatomic narrowings: (1) the cricopharyngeus muscle at the thoracic inlet, (2) the level of the aortic arch, and (3) the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).2 Most objects, once they reach the LES, pass without incident through the intestinal tract. Large objects (greater than 5 cm long or 2 cm wide) and sharp objects may be exceptions to this rule. In children, esophageal FBs are most commonly found at the cricopharyngeus muscle (approximately 75% of children and 25% of adults). Conversely, retained esophageal FBs in adults are more commonly found at the LES (approximately 70% of adults and 10% of children).

Diagnosis

Clinical suspicion should be confirmed with an anteroposterior (AP) and lateral chest and abdominal radiograph, as well as a lateral neck radiograph. Coins in infants and children appear circular on the AP film and flat on the lateral film because of the flat coronal orientation of the esophagus within the mediastinum. In the airway, however, coins may appear either flat or “on edge” on the AP radiographs. Patients who have swallowed food boluses should similarly undergo plain radiography to look for imbedded bones. An esophagogram with barium or Gastrografin is indicated for radiolucent ingested objects. Computed tomography (CT) of the esophagus is reliable for identifying FBs in the esophagus and is superior to plain films for identifying fish or chicken bones (successful in up to 83% of patients with negative plain radiographs).

Clinical Complications

Retained esophageal FBs can cause a wide range of complications, the severity of which is often related to the duration of the entrapment. Complications include mucosal scratches or abrasions, esophageal stricture, retropharyngeal abscess, and esophageal perforation leading to fistula formation, mediastinitis, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, vascular injuries, and pericarditis or pericardial tamponade. Small disk batteries pose a substantial threat, because esophageal necrosis and perforation can occur within 6 hours.

Management

Management depends on the location and type of object as well as the clinical circumstances. Any evidence of airway compromise (e.g., stridor, wheezing, dyspnea) should be managed first by securing the airway if respiratory failure is imminent, followed by urgent consultation for endoscopic removal. If there is evidence for complete esophageal obstruction (i.e., drooling), the patient should be kept in the sitting position with a suction catheter to aid with oral secretions.

Uncomplicated retained FBs can be removed by other techniques. Single, smooth, and blunt radiopaque items that have been retained for less than 72 hours can be removed with the use of a Foley catheter. This procedure is most commonly performed on objects retained high in the thoracic inlet and is often done under fluoroscopic guidance. Removal is successful more than 90% of the time, but the patient may be at risk for aspiration.1,2 If the FB is at the distal esophagus, is smooth and not caustic, and has been retained for less than 24 hours, a period of observation and oral feeding is reasonable. However, FBs should not be allowed to remain in the esophagus.1

Retained button batteries in the esophagus are a serious threat and require urgent transfer and removal to prevent burns (within 4 hours) and perforation (within 6 hours). Batteries located less than 15 mm beyond the gastroesophageal junction may be observed, with repeat radiography in 1 week if the battery does not pass. If the battery is more than 15 mm past the gastroesophageal junction, repeat radiography within 48 hours is recommended. Endoscopic removal is indicated if the battery is still in the stomach after 48 hours.3

REFERENCES

1. McGahren ED. Esophageal foreign bodies. Pediatr Rev 1999;20:129-133.

2. Chen MK, Beierle EA. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Pediatr Ann 2001;30:736-742.

3. Litovitz T, Schmitz BF. Ingestion of cylindrical and button batteries: an analysis of 2382 cases. Pediatrics 1992;89:747-757.

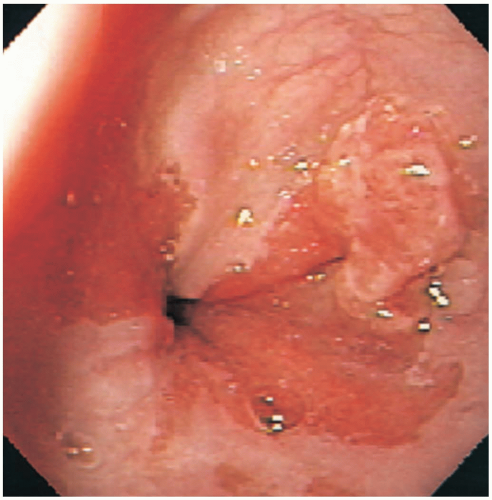

9-4 Barrett’s Esophagus

John Curtis

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

The chronic reflux of gastric contents causes damage to the esophageal epithelium. During the healing process, the mucosa takes on the characteristics of specialized intestinal cells. This abnormal mucosa is at increased risk for neoplastic transformation; esophageal adenocarcinoma develops at the rate of 0.5% per patient-year.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by endoscopy. The typical whitish squamous epithelium is seen to be replaced by beefy red columnar epithelium, more typical of intestinal columnar epithelium.1 Biopsy confirms the intestinal morphology of the epithelium and allows for detection of the dysplasia associated with neoplastic transformation.

Clinical Complications

Adenocarcinoma may complicate untreated Barrett’s esophagus.

Management

Antireflux therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or histamine H2 receptor blockers does not effectively reduce the incidence of carcinoma. Antireflux surgery, however, has been shown to cause regression.2 For patients with documented Barrett’s esophagus, surveillance and therapy are determined by the findings on endoscopy. For those without dysplasia, routine endoscopy is recommended every 3 to 5 years. For those with low-grade dysplasia, repeat endoscopy at 6 and 12 months should be followed by annual evaluations to screen for progression.1,2,3 High-grade dysplasia is treated with esophagectomy or intensive surveillance in suitable candidates. In those patients who are deemed to be poor surgical candidates, endoscopic ablation is a potential option.3

REFERENCES

1. Spechler SJ. Managing Barrett’s oesophagus. BMJ 2003; 326:892-894.

2. Gurski RR, Peters JH, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Bremner CG, Chandrasoma PT, DeMeester TR. Barrett’s esophagus can and does regress after antireflux surgery: a study of prevalence and predictive features. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:706-712, discussion 712-713.

3. Spechler SJ. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med 2002;346:836-842.

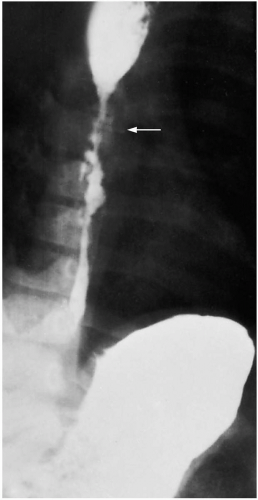

9-5 Esophageal Stricture

Gregory Schneider

Clinical Presentation

Patients with esophageal stricture complain of difficulty swallowing solids, which may progress to difficulty swallowing liquids. Patients may also complain of painful swallowing.1

Pathophysiology

More than 90% of esophageal strictures arise as a complication of long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Stricture formation is preceded by ulcerative esophagitis, leading to full-thickness esophageal inflammation and eventually to scar tissue and contraction. Strictures may also result from ingestion of caustic substances, from extrinsic compression by tumors or anatomic prominences (enlarged thyroid, cardiac or aortic compression), or from surgery. Strictures may also be congenital.1,2

Diagnosis

History is the key to suspecting esophageal stricture. Patients typically have a history of dysphagia and long-term GERD. Barium swallow esophagography should be performed to look for a narrowing of the esophagus. Once an esophageal stricture is identified, patients must be referred to a gastroenterologist for endoscopy and biopsy to rule out a malignancy. Antacid therapy should also begin once a stricture is diagnosed.1,2

Clinical Complications

Management

Endoscopy and biopsy are required in every new case. Once malignancy is ruled out, the patient usually undergoes a series of esophageal dilations. This treatment has been shown to effectively and safely manage esophageal strictures. If it is performed properly, the percentage of esophageal rupture is less than 1%.1,2

REFERENCES

1. Henderson RD. Management of the patient with benign esophageal stricture. Surg Clin North Am 1983;63:885-903.

2. Broor SL, Raju GS, Bose PP, et al. Long term results of endoscopic dilatation for corrosive oesophageal strictures. Gut 1993;34:1498-1501.

9-6 Esophageal Diverticula

Christopher Keane

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

An esophageal diverticulum is an outpouching of the esophagus. A true diverticulum contains all layers of the intestinal tract wall. A false diverticulum (pseudodiverticulum) occurs when the mucosa and submucosa herniate through a defect in the muscular wall. Most esophageal diverticula are thought to be caused by an underlying motility disorder. However, structural lesions, incomplete relaxation of the upper or lower esophageal sphincter, or stricture may also play a role. Symptoms may be related to the location of the diverticulum. Zenker’s diverticula are located in the hypopharynx. Midesophageal diverticula are rare. Diverticula occurring in the lower esophagus (6 to 10 cm from the lower esophageal sphincter [LES]) are called epiphrenic diverticula.1 Rarely, esophageal intraluminal diverticulosis occurs, in which numerous, 1- to 4-mm, saccular outpouchings form in the wall.1

Diagnosis

The physical examination findings usually are normal. In Zenker’s diverticulum, patients may present with a neck mass or halitosis. Patients may also have signs of aspiration pneumonia. Barium swallow esophagography is the radiographic test of choice. Endoscopy, esophageal manometry (indispensable for detection of any motor alterations, which are often at the root of the pathogenesis for the diverticulum), and 24-hour pH monitoring are all used to diagnose this condition. Laboratory testing is generally not helpful.1,2,3

Clinical Complications

Recurrent aspiration pneumonia can complicate large esophageal diverticula. Carcinoma, fistulization, and perforation are uncommon complications.2

Management

Asymptomatic patients can benefit from surveillance. Patients with pulmonary aspiration may require surgery.3

REFERENCES

1. Dado G, Bresadola V, Terrosu G, Bresadola F. Diverticula of the midthoracic esophagus: pathogenesis and surgical treatment. Surg Endosc 2002;16:871.

2. Lopez A, Rodriguez P, Santana N, Freixinet J. Esophagobronchial fistula caused by traction esophageal diverticulum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;23:128-130.

3. Ipek T, Eyuboglu E. Laparoscopic resection of an esophageal epiphrenic diverticulum. Acta Chir Belg 2002;102:270-273.

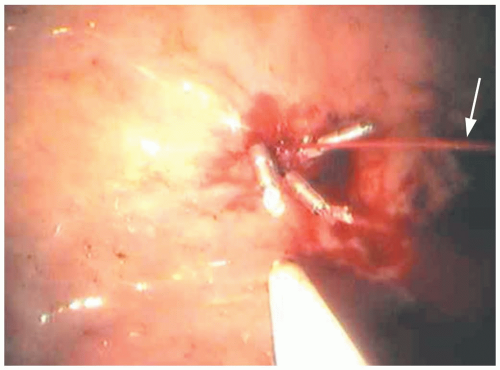

9-7 Achalasia

Cameron Symonds

Jonathan Glauser

Clinical Presentation

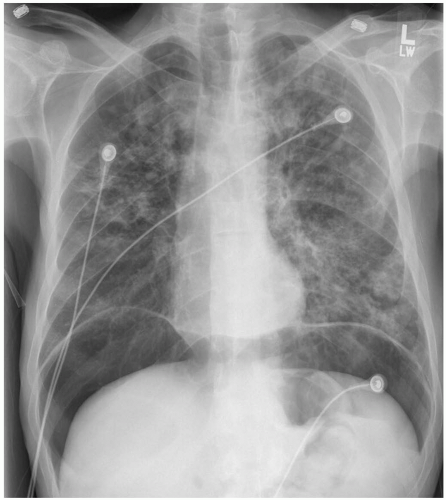

Patients with achalasia present with dysphagia, chest pain, regurgitation, weight loss, and coughing. Dysphagia occurs with both solids and liquids, differentiating the process from obstructive strictures and tumors. Swallowing may be improved by standing or by raising the arms above the head. The chest pain is characterized by retrosternal burning pain and is precipitated by eating. Regurgitation can lead to nocturnal cough, aspiration, and respiratory distress. Patients with advanced disease commonly have significant weight loss. Age at onset typically ranges from 25 to 60 years.

Pathophysiology

Achalasia is a primary motility disorder of the esophagus characterized by a lack of esophageal peristalsis and a hypertonic lower esophageal sphincter (LES). There is an absence of inhibitory ganglion cells throughout the esophageal wall, resulting in unopposed acetylcholine stimulation of the LES and resultant hypertonicity. Persistently elevated pressures lead to mechanical dilation of the esophageal wall and decreased peristalsis.

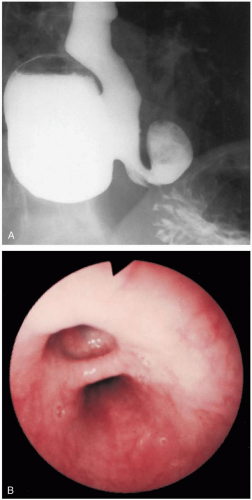

Diagnosis

Barium esophagography is the initial study of choice. Classically, the contrast medium is retained in the atonic esophagus and the nonskeletal muscular distal esophagus is dilated. The dilatation tapers abruptly at the LES, creating a “bird-beak” appearance on the film. A chest radiograph may demonstrate a double mediastinal stripe and a retrocardiac air-fluid level. Endoscopy may rule out malignancy, stricture, or coexistent pathology such as candidal infection. Esophageal manometry is useful if radiographs are equivocal.1

Clinical Complications

Chronic irritation of the esophageal mucosa can cause esophagitis, metaplasia, or squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Nocturnal cough and aspiration may occur.

Management

Therapy is palliative and is directed at relieving obstructive symptoms. Calcium-channel blockers and nitrates can improve LES relaxation and offer mild symptomatic relief early in the course of the disease. Endoscopically guided injections of botulinum toxin into the hypertonic LES produce transient focal neuromuscular paralysis. Symptoms recur in most patients by 1 year. Mechanical dilation or myotomy of the LES has been successful in more than 50% of cases.2

REFERENCES

1. Ferguson MK. Achalasia: current evaluation and therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 1991;52:336-342.

2. Patti MG, Fisichella PM, Perretta S, et al. Impact of minimally invasive surgery on the treatment of esophageal achalasia: a decade of change. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:698-703.

9-8 Candidal Esophagitis

Jason Kitchen

Clinical Presentation

Patients with candidal esophagitis present with dysphagia, odynophagia, and retrosternal pain. Occasionally, they may have only constitutional symptoms such as fever.1

Pathophysiology

Candida albicans is the species implicated in most patients with candidal esophagitis. Little is known about host and yeast factors involved in the pathogenesis of esophageal candidiasis, but they are most likely to be similar to those involved in oral candidiasis (defects in either T-helper or T-suppressor cell function, accompanied by increased transformation of Candida blastoconidia to the more invasive hyphal phase).1

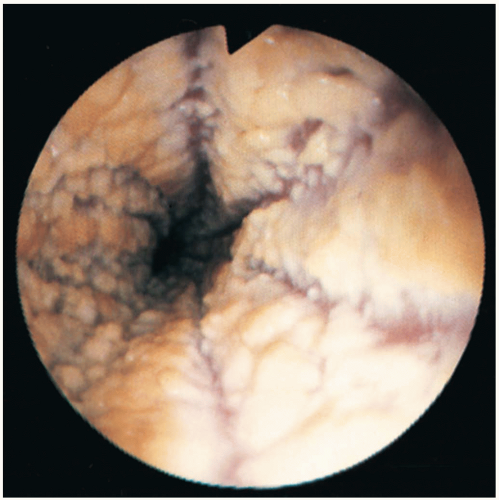

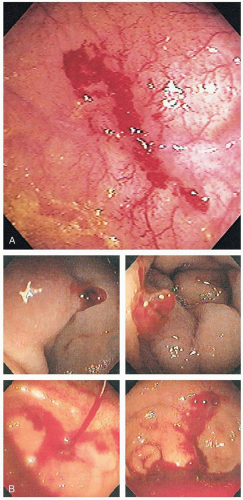

Diagnosis

Endoscopy provides the most rapid diagnosis and the one with the highest sensitivity. The characteristic endoscopic appearance is yellow-white plaques on an erythematous background, with varying degrees of ulceration. However, erythema in the absence of plaques may be the only finding. Biopsy is the only definitive method of diagnosis. In patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), it is not uncommon to identify more than one agent causing esophagitis.1

Clinical Complications

Candidal esophagitis occurs late in the natural history of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection, and usually at a low CD4-positive T-cell count. Cases refractory to antifungal therapy are indicative of worsening immunosuppression on course to a nonfunctional immune system. Treatment success is limited, and recurrence is common. Treatment that focuses more on the dysfunctional immune system in these patients (e.g., highly active antiretroviral therapy) may yield better results.2

Management

Oral and intravenous fluconazole are the drugs of choice. Intravenous amphotericin B is used primarily for azole-refractory cases. In uncomplicated cases, an oral course of therapy may be started, and patients may be discharged with arrangements for close follow-up. In complicated or refractory cases, the patient should be admitted for further evaluation and intravenous therapy.1

REFERENCES

1. Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Mucosal candidiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2002;16:793-820.

2. Zingman BS. Resolution of refractory AIDS-related mucosal candidiasis after initiation of didanosine plus saquinavir. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1674-1675.

9-9 Mallory-Weiss Syndrome

George S. Kim

Clinical Presentation

Patients with Mallory-Weiss syndrome (MWS) present with acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding after forceful emesis; 10% of patients present with melena alone.1 Most patients are between 30 and 50 years of age. Emesis may initially involve gastric contents with subsequent episodes of vomiting, resulting in hematemesis. In 90% of cases, bleeding ceases spontaneously.1

Pathophysiology

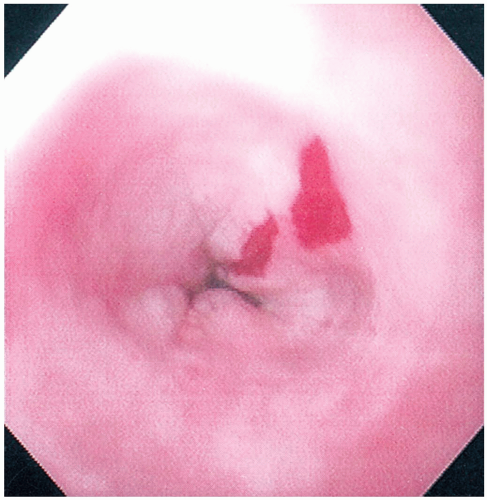

MWS involves partial-thickness tearing of the gastric/esophageal mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction, resulting in upper GI bleeding. MWS accounts for 5% to 15% of upper GI bleeds. MWS tears are caused by a sudden increase of abdominal pressure that causes tears at the gastroesophageal junction.1,2 MWS tears are associated with episodes of vomiting and retching, but heavy lifting, straining, seizures, trauma, colonic lavage, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation have been implicated as well.1 Most MWS tears occur within 2 cm of the cardiac side of the gastroesophageal junction on the lesser curvature of the stomach.1

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by clinical history. Definitive diagnosis is made by endoscopy.

Clinical Complications

Management

Treatment in most cases involves supportive care, fluid resuscitation, H2 receptor blockers, and antiemetics.2 Cases involving severe bleeding require more invasive techniques, such as balloon tamponade or endoscopy for ligation, injection therapy, or electrocoagulation.3 Vasopressin therapy and angiographic embolization also have been employed.2,3

REFERENCES

1. Younes Z, Johnson DA. The spectrum of spontaneous and iatrogenic esophageal injury: perforations, Mallory-Weiss tears, and hematomas. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;29:306-317.

2. Terada R, Ito S, Akama F, et al. Mallory-Weiss syndrome with severe bleeding: treatment by endoscopic ligation. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:812-815.

3. Huang SP, Wang HP, Lee YC, et al. Endoscopic hemoclip placement and epinephrine injection for Mallory-Weiss syndrome with active bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:842-846.

9-10 Boerhaave’s Syndrome

Marco Garza

Clinical Presentation

Presentations of Boerhaave’s Syndrome (BS) range from sepsis and shock to mild pain and vomiting.1 Patients may complain of lower thoracic pain that is progressive and is exacerbated by swallowing or neck flexion. Leakage of air and fluid into the surrounding mediastinal structures may lead to subcutaneous emphysema or a change in the patient’s voice.

Pathophysiology

Boerhaave’s syndrome (BS) occurs predominantly in men (70%) between the ages of 40 and 60 years old.2 Esophageal perforation may result if the upper esophageal sphincter fails to open during emesis and pressure builds in the lower esophagus. Impaired sphincter relaxation may be associated with alcohol, general anesthesia, sedatives, or repeated vomiting. Rupture usually occurs in the distal esophagus (90%), and risk may increase with preexisting esophageal disease. Tears in the mucosa and media vary in length from less than 1 to more than 8 cm. Because the esophagus lacks a serosal layer, rupture of the media exposes the mediastinum to gastric contents. The ensuing inflammation and infection of the mediastinum is the cause of morbidity and mortality associated with esophageal rupture.

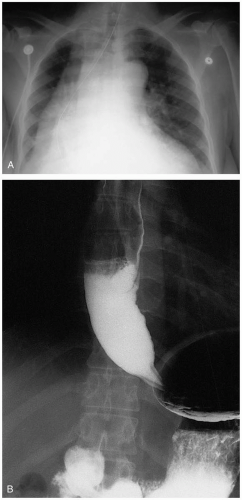

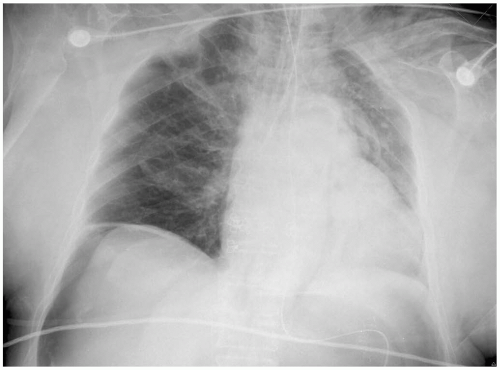

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is often delayed, and BS can be confused with perforated peptic ulcer, myocardial infarction, pancreatitis, dissecting aortic aneurysm, or pneumonia.2 Chest radiographs may be normal, or they may reveal subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, pleural effusions, or a widened mediastinum. Noncontrast chest computed tomography (CT) may reveal small amounts of mediastinal air in the surrounding esophagus, small pleural effusions, and direct communication of the esophagus with the mediastinum.1 The gold standard of diagnostic testing is the contrast esophagogram. A water-soluble contrast agent should be used first, because water-soluble agents are rapidly absorbed and do not cause a significant inflammatory response in the mediastinum.

Clinical Complications

Complications include mediastinitis, sepsis, multiorgan failure, and death. The mortality rate ranges from 5% to 14%, depending on the rapidity of the diagnosis.1

Management

Patients with sepsis or shock require airway management, intravenous fluids, vasopressors, antibiotics, and admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be used, although the mediastinitis is generally chemical and not infectious. H2 receptor blockers or proton pump blockers may also be used. On-site emergency surgical consultation is essential.

REFERENCES

1. Younes Z, Johnson DA. The spectrum of spontaneous and iatrogenic esophageal injury: perforations, Mallory-Weiss tears, and hematomas. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;29:306-317.

2. Reeder LB, DeFilippi VJ, Ferguson MK. Current results of therapy for esophageal perforation. Am J Surg 1995;169:615-617.

9-11 Peptic Ulcer Disease

Derek Halvorson

Clinical Presentation

Patients with peptic ulcer disease (PUD) may present with epigastric pain, belching, bloating, and distention (40% to 70%). The pain may begin after meals (1 to 3 hours after eating in 60% to 90%); it may be improved with eating or with antacids, or it may radiate and follow a daily pattern. Vomiting may represent gastric outlet obstruction resulting from stricture due to chronic inflammation at the pylorus. Sudden, severe pain and abdominal distention or peritoneal signs may represent acute perforation. Hematemesis, melena, and hypotension may occur with significant bleeding. Physical examination findings may be subtle and consist of mild to moderate epigastric tenderness. Patients with acute perforation or bleeding may develop hypotension, melena, hematemesis, or peritoneal signs.

Pathophysiology

PUD results from a breakdown of the normal mucosal barrier of the stomach and intestine by high concentrations of acid and pepsin. The two main causes for this breakdown are Helicobacter pylori infection and use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).1 Other causes include severe physiologic stress (e.g., burns), central nervous system trauma, surgery, and rare hypersecretory states such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Chronic medical conditions such as renal or hepatic failure, pulmonary diseases, radiation, or chemotherapy may also lead to the destruction of mucosal protection. Factors that may potentiate PUD include smoking, alcohol use, steroid use, psychological stress, and bisphosphonates. H. pylori infections are the most common cause of PUD (90% of duodenal ulcers and 70% to 75% gastric ulcers). They produce PUD via inflammatory, mucoprotective, and hormonal influences.1 NSAID use causes a suppression of protective gastric prostaglandins that leads to a weakening of the mucosal protective barrier.2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is suspected by the clinical history and physical examination findings and confirmed by contrast radiography or endoscopy.

Clinical Complications

Complications include bleeding, perforation, and obstruction.

Management

Patients who present with symptoms consistent with PUD should have consideration of other, non-PUD diseases (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, pancreatitis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection) and PUD-related complications (e.g., gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, perforation). A stool guaiac test should be performed, and use of a nasogastric tube (NGT) should be considered if there is a history of hematemesis. Patients should be instructed to cease NSAID use and smoking. Treatment for PUD should be instituted early and may include use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2 receptor antagonists, or sucralfate.2 Patients should be referred to their primary care physician for further management and possible H. pylori testing and treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Chan FK, Leung WK. Peptic-ulcer disease. Lancet 2002;360:933-941.

2. Soll AH. Consensus conference. Medical treatment of peptic ulcer disease: practice guidelines. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. JAMA 1996;275:622-629.

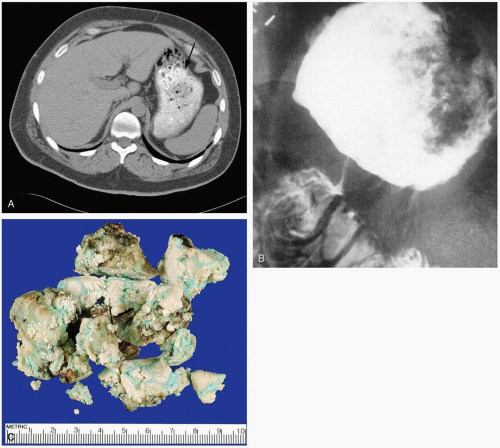

9-12 Bezoars

Robert Hendrickson

Bezoars are masses of food (phytobezoars), medication (pharmacobezoars), hair (trichobezoars), or other ingested items that conglomerate in the stomach or intestine.1

Clinical Presentation

Patients with bezoars may present with a painless epigastric mass, weight loss, anemia, or obstruction of the bowels. Patients at highest risk are children with pica and adults with previous gastric surgery or psychiatric disorders, including trichotillomania (urge to pull one’s hair) or trichophagia (urge to eat one’s hair).1 Bezoars may be found in patients who chronically ingest fibrous materials (e.g., pistachio nut shells, sunflower seeds). Lactobezoars, or bezoars of formula or milk, may be seen in neonates.1

Diagnosis

The diagnosis may be suspected clinically and is confirmed with visualization of a large density filling the stomach on radiography or computed tomography (CT) scan.1

Clinical Complications

Complications include acute obstruction of the gastric outlet or bowel and chronic obstruction of the stomach leading to malnutrition, anemia, and weight loss.1

Management

Small bezoars may be removed via endoscopy, whereas larger bezoars may require operative removal. Chemical dissolution has been attempted in the past with inconsistent results.1

REFERENCES

1. Phillips MR, Zaheer S, Drugas GT. Gastric trichobezoar: case report and literature review. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73:653-656.

9-13 Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Swapan Dubey

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) ranges from massive hematemesis to an asymptomatic positive random stool sample.

Pathophysiology

UGIB is defined as any bleeding that occurs proximal to the ligament of Treitz in the distal duodenum. The majority of UGIB results as a consequence of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) (caused by H. pylori or use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] or alcohol). Mallory-Weiss tears, esophageal varices, and gastritis are less common causes of UGIB.1,2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis can be made by inspection of the patient’s emesis or by placing a nasogastric tube (NGT) and detecting frank blood, blood-stained fluid, or “coffee grounds.” The return of a clear aspirate, however, may simply indicate bleeding has stopped, is intermittent, or cannot be detected due to pyloric spasm.

Clinical Complications

Complications of UGIB include hemodynamic instability, surgical morbidity, and infection by blood-borne pathogens from transfusions.

Management

Maintenance of a patent airway and restoration of intravascular volume are the goals of preliminary management. Initial crystalloid infusion, up to 30 mL/kg, may be followed by transfusion of O-negative or crossmatched blood as needed. Patients with active bleeding require emergency consultation for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Those without active bleeding may be monitored, observed, and possibly scheduled for an EGD.1 Interventions during EGD include submucosal injection of epinephrine, sclerotherapy, and band ligation. If these measures fail to stop the bleeding, angiography with embolization or surgery may be necessary. For those patients with presumed variceal bleeding, medical management may be initiated while awaiting definitive care. Octreotide may be used to lower portal venous pressures, and a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube may be placed as a temporizing measure (see “Variceal Bleeding”).1

REFERENCES

1. Dallal HJ, Palmer KR. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract: upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. BMJ 2001;323:1115-1117.

2. McGuirk TD, Coyle WJ. Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1996;14:523-545.

9-14 Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Swapan Dubey

Clinical Presentation

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Patients with LGIB should have a nasogastric tube (NGT) placed to exclude a lesion proximal to the pylorus. Historical and physical features may help determine the location of bleeding. Red blood streaks or blood found only on toilet paper may imply an anal source. Bright red or maroon stool (hematochezia) may imply a distal source of bleeding (in about 90% of cases).1 Melena results from the oxidation of hematin and is typically associated with lesions of the upper GI tract but may have a lower GI tract focus. Anoscopy may reveal a bleeding internal hemorrhoid, but in up to 25% of cases melena is associated with a second, more proximal source of bleeding.1

Clinical Complications

Complications include cardiac ischemia and cerebral hypoperfusion resulting from blood loss.

Management

Initial resuscitation of the unstable patient may include airway management and resuscitation with crystalloid and blood products. Evaluation of the hemoglobin/hematocrit, platelet count, and a coagulation profile should be performed. Patients with massive LGIB should have surgical consultation and may require angiography for localization and therapeutic embolization. Colonoscopy may be performed for patients with less severe or intermittent bleeding. In addition, red blood cell (RBC) scans may be used for identification of continued bleeding and general localization of bleeding.2

REFERENCES

1. Peter DJ, Dougherty JM. Evaluation of the patient with gastrointestinal bleeding: an evidence based approach. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1999;17:239-261.

2. Zuccaro G Jr. Management of the adult patient with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:1202-1208.

9-15 Black Stool

Robert Hendrickson

The emergency physician may be confronted by a patient whose chief complaint is black stools, or black stool may be discovered during care of a patient with other complaints. Melena is the maroon or black stool produced by bleeding in the upper GI tract. It is typically thick and tarry and produces a positive bedside occult blood test. Ingestion of iron supplements, antacids, and bismuth-containing products (e.g., Pepto-Bismol) may turn stool dark, but in all of these cases the bedside occult blood test is negative.1

FIGURE 9-15 Black, tarry stool as seen on digital rectal examination. (Copyright James R. Roberts, MD.) |

REFERENCES

1. Rockey DC. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:38-46.

9-16 Ingested Foreign Bodies

Maria Halluska

Clinical Presentation

Patients with ingested foreign bodies (FBs) may present with anxiety, difficulty swallowing, drooling, violent retching, and pain localized anywhere from the mouth and throat to the neck or substernal or epigastric area. Pediatric patients present with refusal to eat, vomiting, gagging, choking, stridor, drooling, and pain.1,2

Pathophysiology

Although ingested FBs may become lodged anywhere in the digestive tract, they are most often found within one of several physiologic areas of relative constriction. In the pediatric patient, these areas are all located within the esophagus and include the cricopharyngeal narrowing (C6), the thoracic inlet (T1), the aortic arch (T4), the tracheal bifurcation (T6), and the hiatal narrowing (T10-11). In children most ingested FBs lodge in the proximal third of the esophagus, whereas in adults most ingested FBs lodge at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Risk factors in adult patients include dentures, esophageal abnormalities, alcohol consumption, prisoner status, a psychiatric disorder, and mental retardation.1,2 Ingested FBs are also common in incarcerated persons.

Diagnosis

A history of ingested FB, the time of ingestion, the item ingested, and a careful examination are key to proper diagnosis. In the instance of radiopaque FBs, plain radiographic films of the neck and chest help localization of the item and planning of the removal strategy. If the ingested FB is not localized by these techniques, more invasive measures may need to be undertaken, including direct or indirect laryngoscopy, contrast plain films, computed tomography (CT), endoscopy, or some combination of these. Most FB ingestions result in spontaneous passage; however, 10% to 20% of cases require some medical intervention, with 1% needing surgical intervention.1,2

Clinical Complications

Management

Most ingested FBs can ultimately be managed conservatively, but airway patency is the first priority. Patients who have ingested sharp objects usually require imaging, endoscopy, and/or surgery for removal. Early consultation for these services is essential. Patients at risk for perforation require water-soluble contrast imaging to rule out this complication, and those at risk for aspiration should receive nasogastric tube (NGT) removal of any material proximal to the obstructing object. Those patients who are symptomatic and those with high-risk ingestions need esophagoscopy and observation for signs of complications.

REFERENCES

1. Wahbeh G, Wyllie R, Kay M. Foreign body ingestion in infants and children: location, location, location. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2002;41:633-640.

2. Passey JC, Meher R, Agarwal S, Gupta B. Unusual complication of ingestion of a foreign body. J Laryngol Otol 2003;117:566-567.

9-17 Small Bowel Obstruction

Lalena Yarris

Clinical Presentation

The most common symptoms of small bowel obstruction (SBO) are abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea and vomiting, and an inability to pass flatus or stool. Proximal obstruction is more likely to cause early nausea and vomiting and causes less abdominal distention than distal obstruction does. Although obstipation is classically associated with SBO, a partial obstruction may allow passage of flatus or stool, including diarrhea. Because it takes 12 to 24 hours for the colon to empty, even a complete obstruction can manifest with diarrhea early in the clinical course.1

Pathophysiology

The stomach, small bowel, biliary tract, and pancreas collectively secrete 8 to 10 L of fluid daily. Intestinal obstruction prevents the passage of this fluid to the colon, where it can be reabsorbed. As the fluid collects proximally, intraluminal pressure develops, which accounts for the clinical symptoms associated with SBO. As the pressure builds, the intestine is at risk for development of edema and eventually ischemia.1

Diagnosis

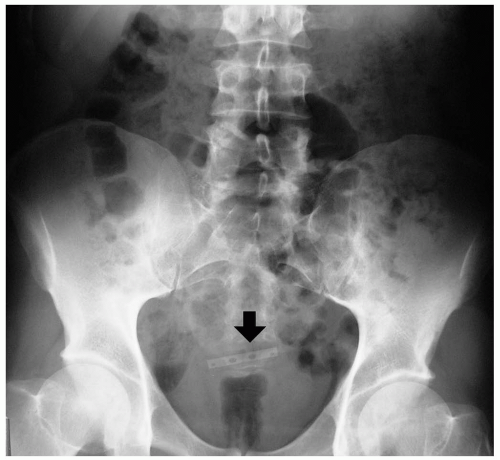

The diagnosis is primarily clinical, but laboratory studies may help in determining the severity of the process. Fever, tachycardia, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count, electrolyte or metabolic abnormalities, and peritoneal signs are suggestive of infection or bowel ischemia. Physical examination usually is significant for abdominal distention and tympany to percussion.

The most appropriate early imaging study is an abdominal series of plain radiographic films. Findings may include intestinal dilatation proximal to the obstruction and a paucity of bowel gas distally, as well as air-fluid levels.2 Computed tomography (CT) scanning may demonstrate small bowel dilatation and air-fluid levels. The sensitivity and specificity of CT scanning for intestinal obstruction are 93% and 100%, respectively.3

Clinical Complications

Complications include hypovolemia, electrolyte abnormalities, acid-base disturbances, strangulation, bowel necrosis, sepsis, and death.

Management

Early surgical consultation is important in suspected intestinal obstruction. Patients with SBO should receive early fluid resuscitation, placement of a nasogastric tube (NGT), and admission to the hospital. Symptomatic treatment with antiemetics and narcotic analgesia is appropriate. Although some cases of intestinal obstruction resolve on their own, 50% to 70% require surgery. The overall mortality rate approaches 2%.2

REFERENCES

1. Miller G, Boman J, Shrier I, Gordon PH. Etiology of small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg 2000;180:33-36.

2. Maglinte DD, Heitkamp DE, Howard TJ, Kelvin FM, Lappas JC. Current concepts in imaging of small bowel obstruction. Radiol Clin North Am 2003;41:263-283.

3. Ogata M, Imai S, Hosotani R, et al. Abdominal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of strangulation in small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg 1994;81:421-424.

9-18 Large Bowel Obstruction

Lalena Yarris

Clinical Presentation

Patients with colonic obstruction usually present with abdominal distention and crampy, abdominal pain. Nausea and vomiting typically occur after the onset of pain. Obstipation may result if the large bowel obstruction (LBO) is complete. Patients with an incompetent ileocecal valve may present with symptoms suggestive of a small bowel obstruction (SBO). In most patients with a competent ileocecal valve, there is a “closed loop” between the valve and the obstruction. Because there is a finite area of colon and luminal space between these two points, obstruction may lead to massive distention and an increased risk of bowel perforation or bowel wall ischemia.1

Pathophysiology

LBO refers to a bowel obstruction that prevents the free passage of fluid and intestinal contents through the colon. The three most common causes for LBO are colorectal cancer (59%), volvulus (17%), and scarring associated with diverticulitis (12%).1 Obstruction of the colon leads to distention of the proximal section of colon, resulting in increased intraluminal pressure. If the intraluminal pressure exceeds the venous pressure, the intestinal wall becomes edematous and no longer absorbs fluids. Intraluminal and interstitial fluid accumulates until the wall pressure exceeds the arterial pressure, and the bowel segment becomes ischemic.1

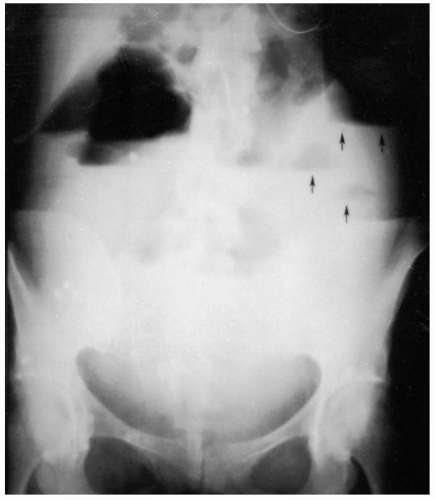

Diagnosis

Patients with a history and physical examination suggestive of LBO require plain radiographic films of the abdomen. The abdominal series usually contains an upright and supine abdomen radiograph, as well as an upright chest or left lateral decubitus view to identify free air under the diaphragm. Radiographic findings in LBO include colonic distention with air-fluid levels within the colon. The large bowel is often distended proximal to the obstruction and decompressed distally. Cecal distention of greater than 12 cm often requires surgical intervention. Distended colon often can be differentiated from small bowel by the presence of haustra and the absence of plicae circulares. However, with ileocecal incompetence or if the bowel is very distended, it may be very difficult to differentiate between the two with plain films. A barium or Gastrografin enema often can confirm the diagnosis of colonic obstruction and identify the point of obstruction.1 Colonoscopy may be performed in Ogilvie’s syndrome (isolated paralytic ileus of the colon without mechanical obstruction) and volvulus. Computed tomography (CT) may also be helpful in identifying mass lesions and determining the point of transition in obstruction.

Clinical Complications

Complications of LBO include perforation, peritonitis, and sepsis. All of these complications can be life-threatening, and the mortality rate associated with a cecal perforation approaches 30%.1

Management

Early management of colonic obstruction is symptomatic and supportive. The administration of analgesics and antiemetics is appropriate, and patients should be given nothing by mouth. Nasogastric decompression and fluid resuscitation should be initiated, and emergency, on-site surgical consultation should be obtained. Findings that may necessitate emergency laparotomy include cecal distention greater than 12 cm, peritoneal free air, evidence of peritonitis, and sepsis. All patients with obstruction require admission to the hospital.1

REFERENCES

1. Lopez-Kostner F, Hool GR, Lavery IC. Management and causes of acute large bowel obstruction. Surg Clin North Am 1997;77:1265-1290.

9-19 Ileus

Lalena Yarris

Clinical Presentation

Patients with a paralytic ileus present with abdominal distention, vomiting, and sometimes obstipation. The constant pain of colicky exacerbations associated with small bowel obstruction (SBO) is often absent, but frequently abdominal discomfort is associated with the distention. Quiet or absent bowel sounds are classically described, but this is an inconsistent physical finding associated with adynamic ileus. Laboratory studies are often normal. Plain abdominal radiographs may show dilated loops of small bowel with air-fluid levels. It can be difficult to distinguish ileus from mechanical obstruction. However, distention of the entire length of the colon is more common in paralytic ileus.1,2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree