Key Clinical Questions

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and other esophageal disorders account for a significant number of physician office visits, hospital admissions, and endoscopic procedures each year. Annual management costs for GERD alone have been estimated to exceed $9 billion and continue to escalate. GERD results from the back-flowing of gastroduodenal contents into the esophagus, leading to a variety of symptoms including heartburn, chest discomfort, regurgitation, and dysphagia. Compromise in the physiological barrier of reflux at the gastroesophageal junction is believed to be the primary mechanism of reflux. Esophagitis is defined as the presence of signs of inflammation of the esophageal mucosal surfaces, both macroscopically and microscopically. GERD is the most common cause of esophagitis, followed closely by medication-induced and infection-induced inflammation. Symptoms of esophagitis may range from mild chest discomfort to significant dysphagia and odynophagia.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of GERD and esophagitis in the U.S. has been increasing in recent years. Epidemiological studies have shown that approximately 25% of the Western population report having symptoms of heartburn at least once a month, with up to 5% noting daily symptoms. While the prevalence of heartburn symptoms appears to be similar in both genders, female patients less likely possess objective findings of reflux on physiological studies. Moreover, numerous clinical studies have shown a lower response rate to antireflux treatment for female patients. No definite relationship between age and GERD has been concluded. At least one study has suggested less reflux symptoms in older individuals. However, the elderly also seem to possess more severe esophagitis, suggesting a higher prevalence of asymptomatic reflux. Strongly positive association has been demonstrated between obesity and reflux symptoms in clinical studies. An increase in body mass index (BMI) both causes reflux and exacerbates existing symptoms.

Presentation

GERD most typically presents as heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia. Patients often describe heartburn as a retrosternal, “burning” discomfort in the lower chest or epigastric region that often travels up toward the neck region. Symptoms often worsen after meals or when patients are in a supine position. As a result, patients frequently complain of symptoms or exacerbation of symptoms at night that may wake them up from sleep. Physiological studies suggest that gastric distention caused by meals and sleep can each induce transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Dysphagia is a common symptom of GERD, and it is often a result of esophageal mucosal inflammation. However, it is also one of the “alarming” signs of GERD that indicate the need for further evaluation to exclude possible underlying malignancy. Other “alarming” signs of GERD include odynophagia, weight loss, signs of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, advanced age, and a family history of upper GI tract malignancy. When one or more of the “alarming” signs is present, further evaluation with endoscopy or other radiographic imaging should be considered.

|

In addition to the typical esophageal presentation, GERD may also cause a variety of atypical, extra-esophageal manifestations. Coexisting pulmonary disease with GERD occurs commonly, with the diagnosis established in 40% to 80% of asthmatics. Although airway irritation resulting from microaspiration of refluxed contents has been implicated as a possible trigger for asthma, certain medications used for asthma, such as bronchodilators, may also cause transient LES relaxation. However, consistent treatment benefit for asthma has not been demonstrated using acid suppression medications or anti-reflux surgery. Nevertheless, GERD likely plays a role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary disorders such as asthma, chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, aspiration pneumonia, and pulmonary fibrosis, as well as upper airway manifestations such as pharyngitis, laryngitis, or postnasal drip. Oral problems such as dental erosions, halitosis, and aphthous ulcers have also been linked to GERD.

Patients with GERD or esophagitis may also present with non-cardiac chest pain, often described by patients as nonspecific retrosternal discomfort. Such chest discomfort may be a result of mucosal inflammation or esophageal spasm or dysmotility, and it may mimic other causes of chest pain such as acute coronary syndrome or pulmonary disorders. Noncardiac chest pain resulting from esophageal disorders is a common presentation leading to emergency room visits and hospital admission for further workup.

Pathophysiology

The lower esophageal sphincter, a tonic smooth muscle located in the lower esophagus around the gastro-esophageal junction, serves as the major barrier to reflux of gastric content into the esophagus. Disruption in the tonic contractile pressure of the LES may result in the backflowing of gastric content into the esophagus. Such a disruption may present in the form of a general decrease in the tonic pressure of the LES (hypotensive LES) or inappropriate relaxation of the LES not during swallowing (pathologic transient LES relaxation). Many factors have been associated with disruption of the tonic contraction of the LES. For example, a hiatal hernia leads to anatomic disruption of the gastroesophageal junction and is associated with an increased risk of transient LES relaxation. Certain medications such as sedatives, food items such as caffeine and chocolate, and lifestyle behavior including alcohol and tobacco use can also lead to LES relaxation, resulting in GERD symptoms. In addition to LES relaxation, the barrier between the stomach and esophagus may also be pathologically overcome if the intragastric pressure exceeds the tonic contractile pressure of the LES. Most commonly, this situation results from obesity, delayed gastric emptying, or certain postoperative states.

While GERD symptoms are often thought to be a result of the presence of acidic gastric content in the esophagus, leading to burning sensation and inflammation, the backflow of nonacidic contents such as bile can also generate similar symptoms. Since certain diagnostic modalities including pH study and the use of acid-suppression medications for treatment of GERD targets the presence of acid in the esophagus, the identification of nonacid reflux patients would help identify patients who may not respond to common medical therapy for GERD symptoms.

Esophagitis presents with inflammatory changes in the esophageal mucosa, with or without signs of erosion. The inflammatory reactions in the esophagus can be elicited by direct caustic injury, most commonly by acid, trauma, infection, or autoimmune processes. In the case of reflux-induced esophagitis, the diffusion of hydrogen ions into the esophageal mucosa leads to cellular acidification and necrosis. As a result, erosion and inflammatory cells infiltration ensue. Caustic injuries may also be caused by direct erosion or chemical reactions between the substance and the esophageal mucosa.

Differential Diagnosis

A variety of risk factors have been linked to GERD. Certain medications can cause a decrease in LES pressure, including beta adrenergic agonists, alpha adrenergic antagonists, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, narcotics, progesterone, estrogens, and tricyclic antidepressants. Lifestyle behaviors such as smoking, alcohol ingestions, and food ingestion prior to incumbency have been linked to GERD symptoms. Some food items and beverages can also cause heartburn symptoms by reducing LES pressure. Examples include fatty food, chocolate, citrus fruits, tomato-based products, peppermint, vinegar, carbonated drinks, and caffeinated beverages.

In addition to lifestyle behavior and ingestions, other known risk factors for GERD include obesity, gastroparesis, and hiatal hernia. Obesity may lead to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure that can cause LES relaxation. Gastroparesis causes intragastric distention, which may in turn activate stretch receptors of the stomach, resulting in decrease in LES pressure.

|

Inflammation of the esophagus is most commonly related to GERD. Other risk factors for the development of esophagitis include medication, infection, radiation, or less common causes such as autoimmune disorders. Medication-induced esophagitis (“pill esophagitis”) causes direct injury to the esophageal mucosa. Common examples include alendronate, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, iron salts, potassium chloride tablets, quinidine, and tetracycline. However, any medication or foreign object can lead to direct injury and erosion into the esophageal mucosa if its transit through the esophagus is prolonged.

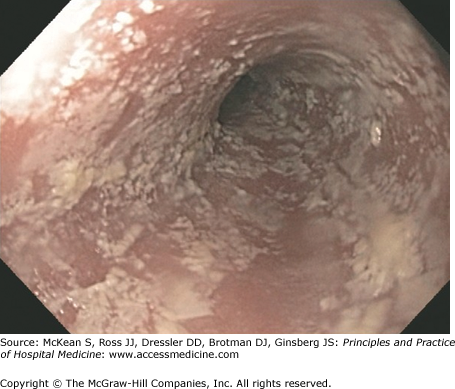

Infectious esophagitis usually occur in immunocompromised hosts such as patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), posttransplantation, or undergoing chemotherapy. The most common etiologies for infectious esophagitis are fungal and viral infections. Esophageal candidiasis is one of the most common opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients (Figure 154-1). Often it represents the initial presentation leading to the diagnosis of HIV infection, and candida esophagitis (unlike simple thrush alone) is an AIDS-defining illness. Patients with esophageal candidiasis often complain of dysphagia and occasionally odynophagia. Esophageal candidiasis appears as whitish plaques on the esophageal mucosa that are easily scraped off, and oropharyngeal disease (thrush) often coexists. Therefore, in immunosuppressed patients who present with dysphagia, a careful oral examination can often provide clues to possible esophageal candidiasis. Empiric treatment with antifungals can often be considered in these high-risk patients. The most common agents causing viral esophagitis are human herpes simplex virus (HSV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV). Similar to fungal candidiasis, HSV and CMV esophagitis often present with dysphagia and odynophagia, although odynophagia presents more commonly in these cases. Concomitant oropharyngeal disease often occurs. Diagnosis requires endoscopic visualization of the typical HSV or CMV ulcers.

Cancer patients with prior chest radiation therapy may also develop radiation-induced esophagitis. Symptom onset can be immediate (within 3 weeks) or delayed (usually 3 or more months), with significant variation in the severity often unrelated to the dosage of radiation received. Symptoms can range from mild dysphagia to severe odynophagia or structuring requiring enteral tube feeding. As these patients are often also immunocompromised from chemotherapy, infectious esophagitis may coexist and must first be ruled out or treated.

Patients with a history of hematologic malignancy who have undergone bone marrow transplantation may develop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract. GVHD of the esophagus often leads to significant inflammation and ulceration, resulting in symptoms of significant dysphagia, odynophagia, or bleeding. Therefore, this diagnosis must be considered in bone marrow transplant patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding or new-onset dysphagia symptoms, and mucosal biopsies can establish the diagnosis. Similar to other cancer patients, infectious esophagitis is also very prevalent in this population and may coexist with GVHD due to chronic immunosuppression.

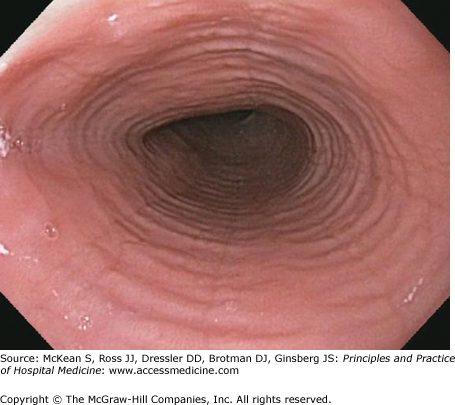

Autoimmune disorders remain an uncommon cause of esophagitis. Inflammatory diseases such as Crohn disease or Behçet disease may involve the esophagus, leading to inflammation and often ulcerations. Another one of such disorders, eosinophilic esophagitis, appears to be increasing in incidence in recent years. Eosinophilic esophagitis is defined by the infiltration of large number of eosinophils in the esophageal mucosa. Etiology of eosinophilic esophagitis remains unclear; however, it is often linked to other allergic disorders such as asthma or dermatitis. Patients with eosinophilic esophagitis are often young and they often first present with an episode of food impaction. While eosinophilic esophagitis can be associated with characteristic endoscopic appearances, its diagnosis requires histopathologic confirmation of eosinophilic infiltration (Figure 154-2).

Diagnosis

GERD diagnosis is most frequently achieved thorough history of classic symptoms combined with response to empiric antacid medical therapy, most commonly a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). A meta-analysis of studies on the diagnostic value of PPI response in GERD revealed a pooled sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 54% (positive likelihood ratio 1.70). In most cases, no further diagnostic testing is needed in patients with typical GERD symptoms who have no alarming signs that resolve with a trial of PPI. However, patients who fail to respond to a trial of PPI or report alarm signs should undergo further diagnostic workup, including endoscopy, radiographic imaging, or physiologic testing such as manometry, impedance, and pH studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree