CHAPTER 19

Gallbladder

Catherine M. Concert, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, AOCNP, NE-BC, CGRN

The most common type of gallbladder condition is the development of gallstones (cholelithiasis). Gallstones are formed from bile crystals. Problems related to gallstones present along a broad clinical spectrum. Most patients with gallstones remain clinically silent. Symptoms in many patients are mild and may be evaluated and treated in the outpatient setting and on an elective basis. In some patients, a gallstone may cause the gallbladder to become inflamed, resulting in pain, infection, or other serious complications. The best screening method to accurately determine the presence of gallstones is ultrasonography (Stinton & Shaffer, 2012).

A number of risk factors predispose patients to gallbladder disease. Nonmodifiable ones include age, female sex, family history, ethnic background, pregnancy, and genetic predisposition. Modifiable factors include diet, obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, rapid weight loss, and reduced physical activity, as well as certain drugs such as thiazide diuretics, octreotide, ceftriaxone, and female sex hormones (Stinton & Shaffer, 2012).

Gallstones can cause a variety of complications requiring hospitalization and rapid intervention. Previously, surgical removal of the gallbladder (open cholecystectomy) from symptomatic patients was the only viable treatment option for most patients with gallstones. This surgical procedure is done less often now that there are endoscopic and medical procedures to treat gallstones. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a technique that has most commonly replaced open cholecystectomy as the surgical procedure of choice for patients with gallstones. This procedure uses smaller incisions, which allows for a quicker recovery and discharge from the hospital within 24 hours (Glasgow & Mulvihill, 2010). Appropriate management of cholelithiasis, especially in emergent situations, requires an interprofessional team approach.

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

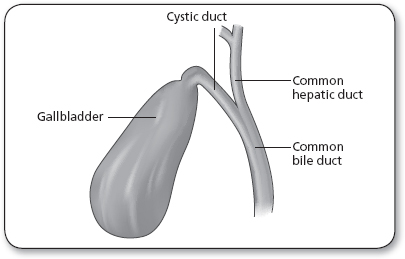

The gallbladder (Figure 19.1) is a pear-shaped, sac-like organ positioned on the right side of the abdomen underneath the liver. It stores bile that is produced by the liver to assist in the digestion of fats. The anatomy of the gallbladder is further described in Chapter 21, “Gastroenterologic Cancers.”

Biliary pain (crampy pain in the middle to right upper abdomen, known as biliary colic) results from impaction of the cystic duct or common bile duct by a gallstone, causing distention of the gallbladder. If left untreated, gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) can cause severe pain (the most common clinical sign) and fever. Surgery is indicated if inflammation persists or recurs (Stinton & Shaffer, 2012; Yokoe et al., 2012). In severe cases of cholecystitis, bile can become entrapped in the gallbladder causing irritation and pressure. Inflammation and necrosis may lead to perforation (Wang & Afdhal, 2010). Acute acalculous cholecystitis is a condition associated with a recent operation, trauma, burns, multisystem organ failure, and parenteral nutrition (Huffman & Schenker, 2010).

Choledocholithiasis is associated with stones obstructing the common bile duct. A gallstone in the common bile duct can distally impact the ampulla of Vater, the area in the duodenal wall where the pancreatic and common bile ducts join. Obstruction of bile flow by a stone in this critical area can cause abdominal pain and jaundice. Stagnant bile above an obstructing bile duct stone can result in bacteria spreading rapidly into the ductal system and liver, producing a life-threatening infection known as ascending cholangitis. A gallstone in the ampulla of Vater can also cause obstruction of the pancreatic duct. This can cause the activation of pancreatic digestive enzymes within the pancreas, initiating acute pancreatitis (Kummerow et al., 2012).

Cholangitis can have significant morbidity and mortality. Patients with acute cholangitis respond to antibiotic therapy; however, in some cases, severe or toxic cholangitis may require emergency biliary drainage. Symptoms associated with cholangitis are intermittent fever accompanied by chills, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice, also known as Charcot’s triad (Lee, 2009). Reynold’s pentad is a more severe form of cholangitis that includes septic shock and mental confusion (Lee, 2009). If left untreated, cholangitis causes mortality rates that can range from 13% to 88% (Fujii et al., 2012).

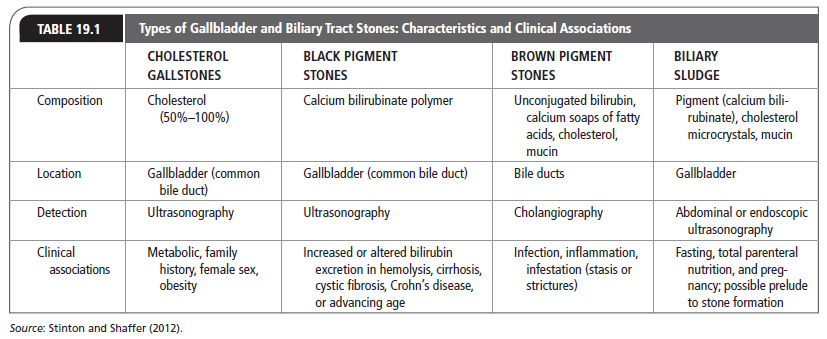

Types of gallstones and their characteristics are described in Table 19.1. Cholesterol stone formation correlates with the metabolic syndrome, a combination of diabetes type 2, abdominal obesity, and hypertriglyceridemia with a common denominator of insulin resistance. Low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) is associated with cholesterol stone formation (Eslick & Shaffer, 2013). Cholesterol stones come from hypersecretion of hepatic cholesterol into the bile with a decrease and hyposecretion of bile salts and phospholipids. Gallbladder abnormalities that contribute to hypomotility, immune-mediated inflammation, and hypersecretion of gelling mucins can also reduce intestinal motility and augment bile salt synthesis by anerobic microflora (Wang, Cohen, & Carey, 2009).

Pigment gallstones, either black or brown, are much less common than cholesterol stones. Black stones form from the bile within the gallbladder; brown stones form secondary to stasis and anerobic bacterial infection in the gallbladder or any part of the biliary tree (Vítek & Carey, 2012). Cholesterol is present in brown- and black-type stones with a mixed mucin glycoprotein matrix secreted by epithelial cells lining the biliary tree. The significant pathophysiological prerequisite for black stone formation is hyperbilirubinbilia (biliary hypersecretion of bilirubin conjugates) primarily due to hemolysis, ineffective erythropoiesis, or pathologic enterohepatic cycling of unconjugated bilirubin (Vítek & Carey, 2012).

Biliary sludge is a thick substance of small cholesterol crystals that are trapped within a mucin gel. Biliary sludge is associated with fasting, total parental nutrition, pregnancy, and use of drugs like ceftriaxone, octreotide, and thiazide diuretics, in addition to pancreatitis. The mucoproteins in biliary sludge are factors that contribute to gallstone formation. The cholesterol microcrystals coalesce and grow into gallstones (Stinton & Shaffer, 2012).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Worldwide, gallstones are a common digestive disorder. The prevalence of gallstones in the United States adult population is about 15% with an annual overall cost of approximately 6 billion dollars (Yadav & Lowenfels, 2013). Gallbladder disease is responsible for 1.8 million ambulatory care visits and 700,000 cholecystectomies per year. It is the most common cause of hospitalization for digestive disorders (Almadi, Barkun, & Barkun, 2012). Higher incidence rates occur in North and South American Indians (Stinton & Shaffer, 2012). American Indians have a prevalence rate of 60% to 70%. In Northern Europe, prevalence is about 20%. There is a low prevalence rate in Saharan Black Africans (Eslick & Shaffer, 2013).

Cholesterol-type gallstones are most common in the United States, accounting for 75% to 80% of gallstones. Approximately 10% to 25% of gallstones are bilirubinate of either black or brown pigment (Qiao et al., 2013). In Asia, pigmented stones predominate, although studies have shown an increase in cholesterol stones in the Far East (Kim, Joo, Lim, & Joo, 2013).

Risk factors for gallbladder cancer include ethnicity and female gender, cholelithiasis, advancing age, chronic inflammatory conditions affecting the gallbladder, and congenital biliary abnormalities (Eslick & Shaffer, 2013). Overall, the all-cause mortality of gallbladder disease has increased with the population, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.30 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.10–1.50; Eslick & Shaffer, 2013).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

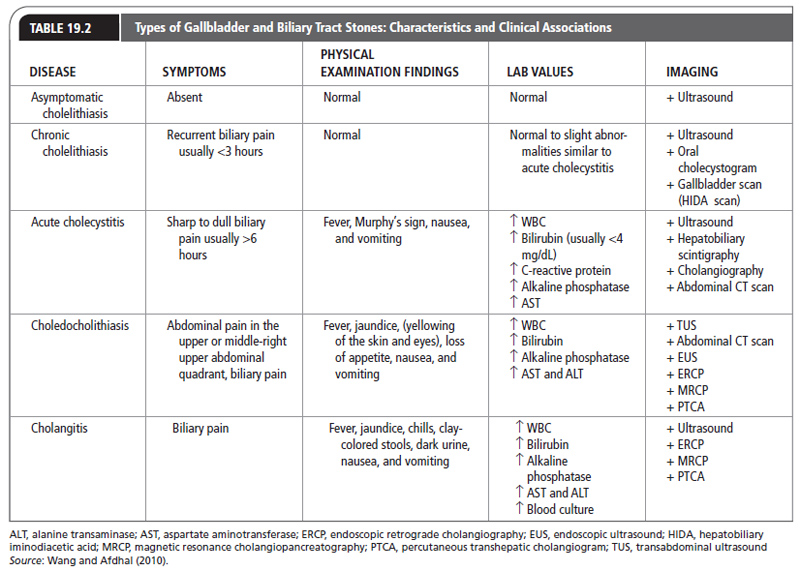

Table 19.2 presents the diagnostic criteria for gallstone-related conditions.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Most cases of cholelithiasis are asymptomatic, and most patients will not proceed to the development of symptoms. International clinical practice guidelines for the management of gallbladder disease are available at http://link.springer.com/journal/534/20/1/page/1. To diagnose gallbladder disease, a comprehensive abdominal examination should be done. Once patients develop clinical stone-related disease, the hallmark complaint is abdominal pain. The primary care provider should examine the patient for Murphy’s sign during an abdominal examination. This maneuver permits the gallbladder to be palpated on inhalation. If the patient experiences pain and stops inhaling when the gallbladder comes into contact with the provider’s fingers, gallbladder disease should be suspected (Kimura et al., 2013). The other characteristics can be nonspecific, and biliary pain has a broad differential diagnosis, including gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, reflux esophagitis, pancreatitis, renal disease, diverticulitis, radicular pain, and angina (Yokoe et al., 2012). Because asymptomatic gallstones are common, the identification of stones in the gallbladder should not preclude a complete evaluation of patients whose symptoms suggest other diagnoses.

Biliary pain has previously been referred to as biliary colic, but most authors agree that the term colic, which implies a spasmodic type of pain, does not accurately describe the pain of patients with gallstones. The pain of cholecystitis usually comes on suddenly and builds to a plateau quickly. It lasts several hours, with gradual resolution (Kiriyama et al., 2013). Uncomplicated biliary pain usually lasts <3 hours (can be as brief as 15 minutes) but may last as long as 24 hours. An episode of pain lasting more than 6 hours is suggestive of acute cholecystitis rather than chronic cholecystitis (Kiriyama et al., 2013). The most common location for biliary pain is the epigastric or right upper quadrant area. The right costal margin is actually the second most likely location in which patients describe their pain (Yokoe et al., 2012). Patients may have pain that is localized or that radiates to the right scapula, back, or shoulder. Atypical symptoms such as fullness, bloating, belching, heartburn, and early satiety are extremely common, especially in the elderly (Yokoe et al., 2012). Restlessness, nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, and low-grade fever are findings frequently associated with biliary pain. The older teaching that pain is precipitated by the ingestion of foods and especially fats is not accurate. Many patients have no such association but likely have their symptoms at night (Yokoe et al., 2012).

Patients with chronic cholecystitis, characterized by recurrent bouts of biliary pain, usually have no fever, no abdominal tenderness, and no jaundice. If patients begin to have symptoms from chronic cholecystitis, the episodes tend to recur with increasing frequency and severity. In addition to being asymptomatic, patients have normal laboratory evaluations for white blood cell counts, bilirubin, liver enzymes, and alkaline phosphatase levels (Afdhal, 2008).

Patients with acute cholecystitis usually have biliary pain and may have fever. About 20% present with jaundice. Abdominal tenderness is common and a positive Murphy’s sign (eliciting pain when palpating the right upper quadrant as the patient takes a deep inspiration) is a classic finding. The white blood cell count is usually elevated, but to <15,000/mm3. The serum bilirubin value may be elevated but is usually <4 mg/dL. Transaminase and alkaline phosphatase levels may also be elevated (Yokoe et al., 2012). Twenty percent of patients may have a palpable mass from the omentum (peritoneum) lying over the inflamed gallbladder (Yokoe et al., 2012).

Choledocholithiasis and cholangitis are difficult to distinguish from each other on clinical grounds. Choledocholithiasis is caused by the presence of a gallstone in the common duct. Cholangitis is an infection of an obstructed bile duct and is usually found in association with choledocholithiasis. Both sets of patients may present with abdominal pain, jaundice, and fever. This combination of symptoms is known as Charcot’s triad and is generally associated with cholangitis, but the same description may apply to patients with choledocholithiasis (Yokoe et al., 2012).

Complications of acute cholecystitis include perforation, Mirizzi’s syndrome, and emphysematous cholecystitis. Perforation may take three forms: localization by abscess formation; free spillage into the peritoneum; or erosion into an adjacent viscus, giving rise to fistula formation (Yokoe et al., 2012). Mirizzi’s syndrome is a phenomenon in which extrinsic compression by surrounding inflammation leads to obstruction of the common hepatic duct or the common bile duct. Certain infections are associated with the production of gas in the gallbladder, the gallbladder wall, the bile ducts, or the pericholecystic area; this is referred to as emphysematous cholecystitis.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Screening asymptomatic patients for gallstones is not supported by available evidence (Kiriyama et al., 2013). Laboratory testing for gallbladder disease should include a complete blood count, liver-function testing, and serum amylase and lipase to help discriminate between the various conditions (Allen, 2013). The laboratory tests that are suggestive of biliary obstruction, as in choledocholithiasis and cholangitis, are elevations of the hepatic transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine transaminase [ALT]), bilirubin (usually >4 mg/dL), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), and alkaline phosphatase (Kirayima et al., 2013; Yokoe et al., 2012). Leukocytosis is also usually present. Blood cultures are usually positive in cholangitis.

In acute cholecystitis, the white count is usually elevated, and in 20% of patients the bilirubin level is also elevated, but less so than when obstruction is present. An elevated AST level is found in 75% of patients with acute cholecystitis (Yokoe et al., 2012). Patients with chronic cholecystitis have normal or mildly elevated laboratory values compared with patients with acute cholecystitis.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is the most important diagnostic tool for identifying gallstones in the gallbladder. It is accurate, quick, readily available, noninvasive, and requires no special preparation. Useful information that may be obtained by ultrasound includes identifying a thickened gallbladder wall, which suggests chronic cholecystitis; assessing the number and size of stones, which can help determine if a patient qualifies for nonsurgical treatment; and identifying a dilated biliary tree, which may mean obstruction of the common duct and choledocholithiasis (Stinton & Shaffer, 2012; Yokoe et al., 2012). Ultrasound has a sensitivity of 50% to 88% and a specificity of 80% to 88% for the detection of fluid immediately around the gallbladder, which can indicate abscess or acute cholecystitis (Yokoe et al., 2012).

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is useful when the primary care provider suspects common bile duct stones, and regular ultrasound does not detect stones when the patient is not clearly ill. However, if common duct stones are detected, they cannot be removed using this method (Wang & Afdhal, 2010). Its accuracy at detecting choledocholithiasis rivals that of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and it carries no risk of pancreatitis. It may be particularly useful for ruling out choledocholithiasis in patients who have contraindications to ERCP or whose risk for choledocholithiasis is low (Yokoe et al., 2012).

Radiography

Plain x-rays are of limited value in assessing gallstones because most gallstones are radiolucent. Only 10% to 25% of stones are rendered radiopaque by the presence of calcium (Tse, Liu, Barkun, Armstrong, & Moayyedi, 2008). The x-ray finding on plain abdominal films that suggests the presence of a gallstone is an incomplete ringed density in the right upper quadrant. Although it is not the method of choice for locating gallstones, information regarding calcium content is essential in evaluating patients for dissolution therapy because only pure cholesterol stones, which are radiolucent, are amenable to this treatment (Tse et al., 2008). Plain x-rays can be useful when ruling out differential diagnoses.

Cholecystography

Oral cholecystography is a second-line test after ultrasound in diagnosing chronic cholecystitis. This study should be considered if ultrasonography fails to identify the gallbladder or if the ultrasound is negative for stones but gallstone disease is still a diagnostic consideration. A halogenated contrast medium is given to the patient orally. The contrast material is secreted into the bile and concentrated in the gallbladder, thus rendering it radiopaque. Gallstones are represented by filling defects within the contrast material. Two-thirds of patients whose gallbladders do not visualize after the first dose of the contrast material will respond to a second dose. Visualization of the gallbladder via cholecystography requires a patent cystic duct. This is an inclusion criterion for both lithotripsy and oral dissolution therapy. Additionally, oral dissolution therapy is more likely to succeed when stones are noted to float in halogenated bile (Tse et al., 2008).

Cholescintigraphy

Cholescintigraphy is a nuclear medicine study that is useful in diagnosing acute cholecystitis. Radioactive-labeled iminodiacetic acid derivatives given intravenously are quickly excreted into the bile. Scans done at 30 to 60 minutes normally show radioactivity in the gallbladder, the common bile duct, and the small bowel. Nonvisualization of the gallbladder because of obstruction of the cystic duct is consistent with acute cholecystitis. Failure to see dye in the small intestine is suggestive of choledocholithiasis (Yokoe et al., 2012).

Computed Tomography

CT scans can be a valuable additional imaging technique if the health care provider suspects complications, such as perforation, common duct stones, or other problems such as cancer in the pancreas or gallbladder (Wang & Afdhal, 2010).

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

ERCP involves injecting contrast dye directly into the biliary tree. Stones may be identified in patients with abdominal pain in whom no other diagnosis can be made and in whom ultrasounds and cholecystograms are negative. However, its main use in gallstone disease is in diagnosing choledocholithiasis and cholangitis. Ultrasonography, as stated earlier, is not very sensitive in identifying common duct stones. Although certain clinical and laboratory findings may suggest these conditions, no set of findings is specific for these diagnoses. When the presence of ductal stones is suspected and when stones cannot be identified in the gallbladder or no common duct dilatation is noted on ultrasound, ERCP may be the method of choice for identifying common duct stones (Yokoe et al., 2012). ERCP can identify tumors causing ductal obstruction. It can also be used as a therapeutic intervention such as in an endoscopic sphincterotomy to remove common duct stones. ERCP may also be used to diagnose biliary dyskinesia (Yokoe et al., 2012). The ERCP technique is invasive and has risks for complications, including pancreatitis.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is useful for detecting common bile duct stones and other abnormalities of the biliary tract. MRCP has a sensitivity of approximately 98% (Allen, 2013). A dye is injected into the patient’s veins to assist with visualization of the biliary tract. MRCP is extremely sensitive in detecting biliary tract cancer. As an imaging procedure, it may not detect very small stones or chronic infections in the pancreas or bile duct. It is most likely to be useful in a small subset of patients who have unclear symptoms that suggest gallbladder or biliary tract problems when ultrasound and other routine tests have been negative. Performing a MRCP in certain patients can eliminate the need for ERCP and its potential risks (Williams et al., 2008).

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

TREATMENT OPTIONS, EXPECTED OUTCOMES, AND COMPREHENSIVE MANAGEMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree