CHAPTER 30 Fusion Surgery and Disc Arthroplasty

Description

Terminology and Subtypes

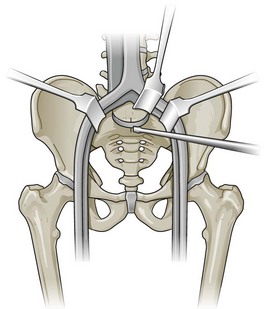

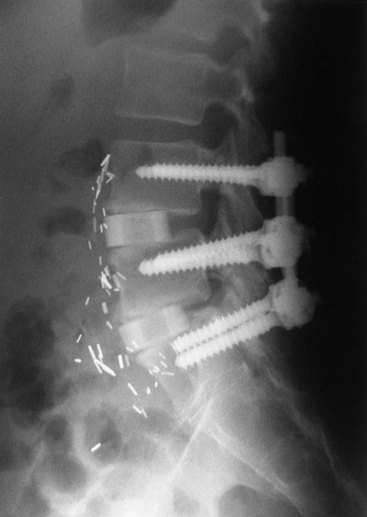

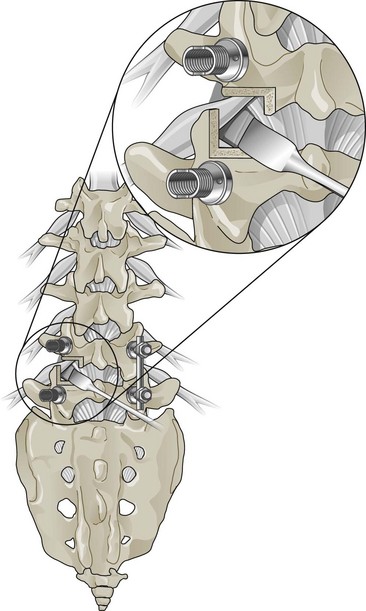

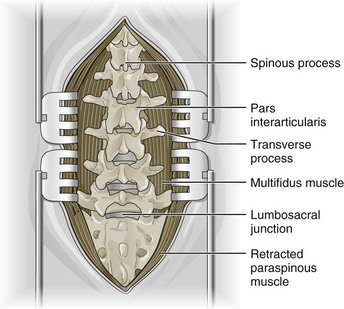

In the context of chronic low back pain (CLBP) and degenerative disc disease (DDD), fusion surgery is a broad term used to indicate various forms of lumbar surgery whose primary goal is to join bony anatomic structures in the lumbar spine that are thought to have excessive movement or otherwise contribute to presenting symptoms. Fusion surgery is also known as arthrodesis. The main types of fusion surgery are named according to the surgical approach taken (i.e., where the incision is made and the direction from which the spine is operated on) and include posterior approaches (Figure 30-1), anterior approaches, and combined anterior and posterior approaches, which are also known as circumferential or 360-degree approaches (Figure 30-2). Posterior approaches to fusion surgery include posterior lateral intertransverse fusion surgery (PLF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery (PLIF), and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion surgery (TLIF) (Figure 30-3). The main anterior approach to fusion surgery is known as anterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery (ALIF).

Figure 30-1 Lumbar fusion surgery: posterior approach.

(From Paz, JC. Acute care handbook for physical therapists, 3rd Edition. St. Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Figure 30-2 Lumbar fusion surgery: circumferential approach.

(From Maxey L, Magnusson J. Rehabilitation for the postsurgical orthopedic patient, ed. 2. St. Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

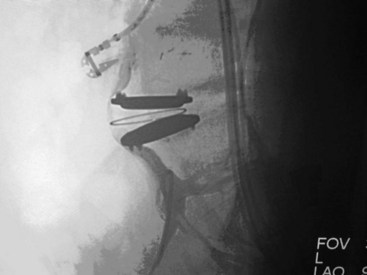

Figure 30-3 Lumbar fusion surgery: transforaminal lumbar interbody approach.

(Adapted from Kim DH, Henn J, Vaccaro AR, Dickman CA (eds). Surgical Anatomy & Techniques to the Spine. Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.)

History and Frequency of Use

In 1891, the first spinal instrumentation procedure was performed by Hadra, who used wires to repair a spinous process fracture.1 Bone augmentation and arthrodesis for the treatment of lumbar DDD initially occurred in 1911, with successful noninstrumented fusion surgery using tibial grafts between spinal processes to stabilize the spine.2 Another technique “feathered” the lamina, decorticated the facet joints, and then added morsalized bone derived from the spinous processes, representing the first documented example of flexible stabilization utilizing autologous bone for reconstructive purposes.3 Kleinberg then pioneered the concept of using bone graft for fusion surgery in 1922.4 In 1933, the ALIF procedure was first documented by Burns.5 Internal fixation as an adjuvant to fusion surgery using bone graft was described shortly thereafter by Venable and Stuck in 1939.6 With an increased understanding of spinal fusion surgery, the PLIF procedure was developed and first performed in 1944 by Briggs and Milligan, who used bone chips collected during the laminectomy procedure in the disc space as an interbody autograft.7 In 1946, Jaslow modified the PLIF procedure by positioning an excised portion of the spinous process within the intervertebral space.8

Instrumentation advances were also occurring in the middle of the 20th century, with the original pedicle fixation procedure described in 1949.9 In 1953, Cloward described a PLIF technique that used impacted blocks of iliac crest autograft, after which the popularity of this approach increased.10 Holdsworth and Hardy were the first to report on internal fixation of the spine in patients with fracture dislocations of the thoracolumbar spine in 1953.11 The use of rigid interbody instrumentation to promote fusion surgery was originally reported in horses by DeBowes and colleagues12 and Wagner and colleagues.13 Boucher was the first to use transpedicular screws for spinal fusion surgeries in 1959.14 Harrington published his results for fusion surgery with instrumentation for scoliosis in 1962.15 Luque developed the segmental stabilization system in the late 1970s, in which two flexible L-shaped rods were wired to each of the vertebrae to correct the curve and achieve a more stable, stronger fixation.16 Bagby followed up this research using a slightly oversized, extensively perforated stainless steel cylinder (the “Bagby Basket”) filled with local bone autograft to restore the intervertebral disc space.17 Butts and colleagues furthered this concept using two parallel implants interposed between the lumbar vertebral bodies and reported achieving immediate stabilization; this technology would eventually become known as the Bagby and Kuslich (BAK) vertebral interbody cage.18

TLIF was introduced by Harms and Rolinger in 1982, enabling placement of the bone graft within the anterior or middle of the disc space to restore lumbar lordosis.19 This procedure preserved the contralateral laminae and spinous processes, making additional surface area available to help achieve a posterior fusion surgery. The first percutaneous screw placement technique was reported by Magerl in 1982 and involved the use of external fixators.20 The Cotrel-Dubousset system for spine surgery was introduced in 1984, followed by the Texas Scottish Rite system in 1991, the Moss Miami system in 1994, the Xia spine system in 1999, and the Expedium system in 2008. Although a large number of these surgical instrumentations, techniques, and devices were originally designed for scoliosis, many were later used to treat patients with DDD and CLBP. The initial discovery of rhBMP was made in 1965 by Urist and colleagues.21 Since then, at least 14 different types have been isolated and analyzed.22

Disc arthroplasty devices were first proposed in the early 1950s.23 Nachemson was the first to begin implanting a silicon testicular prosthesis into the disc space, although this procedure was later abandoned when the implants disintegrated.23 Fernstrom reported his experience with implanting a steel ball in the disc space in 1966, but this also met with poor results.23,24 Since that time, there has been a plethora of failed artificial disc designs including inelastic and elastic devices, silicon spacers, plastic spacers, silicon or plastic spacers with metal end plates, and various end plate designs including screws, pins, keels, cones, and suction caps.25,26 Various hygroscopic agents have also been used, followed by elastic beads, springs, oils, and expandable gels.25 The first such arthroplasty device approved for use in the United States was the Charite artificial disc, which was developed in the mid-1980s at the Charite University Hospital in Berlin, Germany.

Practitioner, Setting, and Availability

According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), there were 17,673 orthopedic surgeons and 4605 residents practicing in the United States as of January 2010.27 Corresponding figures from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) were 3519 neurologic surgeons and 1663 residents/fellows as of December 2009.28 The number of orthopedic and neurologic surgeons with subspecialty training in spine surgery is difficult to estimate because board certification in spine surgery is optional in the United States. The American Board of Spine Surgery (ABSS) was approved as a specialty certification board by the Medical Board of California in 2002 and reported 180 board-certified spine surgeons in the United States as of January 2010 (personal communication, Eckert M. Executive administrator, American Board of Spine Surgery, 2010).

General Surgical Approach

A skin incision is made by the surgeon above the area to be operated on. The length of the incision varies according to the surgical approach. The incision is then made gradually deeper by cutting through subcutaneous tissues and muscular planes, using retractors to maximize visualization (Figure 30-4). Decompression surgery is often performed before fusion surgery or disc arthroplasty to remove disc tissue and bone; that procedure is described in Chapter 29 of this text.

Figure 30-4 Lumbar fusion surgery: complete dissection to maximize visualization of operative field.

(In Shen FH, Shaffrey C: Arthritis and arthroplasty: the spine. Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders. Adapted from Kim DH, Henn J, Vaccaro AR, Dickman CA (eds). Surgical Anatomy & Techniques to the Spine. Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.)

Fusion Surgery

Disc Arthroplasty

To perform disc arthroplasty, a standard anterior approach to the lumbar discs is used, with the patient lying in a supine position (Figure 30-5). After the intervertebral disc has been removed, the artificial disc device will be placed in the intervertebral disc space while held under axial distraction. Positioning of the device should be verified extensively using fluoroscopic guidance in an attempt to preserve alignment with adjacent vertebral bodies and maximize lumbosacral motion. The device remains fixed to the adjacent end plates with small keels.

Regulatory Status

Many of the developmental trends in spine surgery over the past 20 years have been driven by the challenge of achieving arthrodesis in the lumbar spine. Because of this, the FDA has seen a dramatic increase in the number of applications for bone graft substitutes and disc arthroplasty technologies. Currently, there are two genetically engineered rhBMP bone graft substitutes available in the United States. In 2002, rhBMP-2 (Infuse Bone Graft, Medtronic) was approved by the FDA for use in ALIF cage (LT-Cage, Medtronic) procedures, with results subsequently indicating fusion surgery rates superior to those associated with autograft.29 In 2006, rhBMP-7 (Osteogenic Protein-1 [OP-1] Putty, Stryker) was approved by the FDA for revision posterolateral (intertransverse) lumbar spinal fusion surgery.30

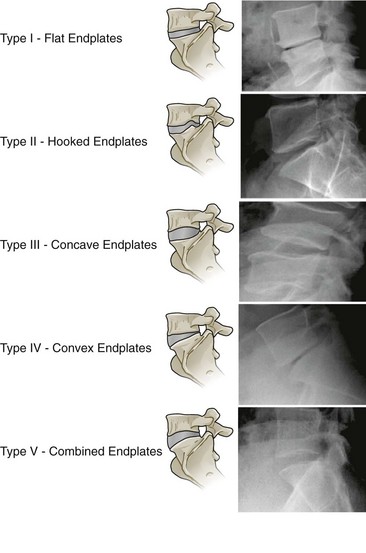

Currently, there are four intervertebral disc arthroplasty devices available in the United States: Charité (Depuy) (Figure 30-6), ProDisc-L (Synthes) (Figure 30-7), Maverick (Medtronic), and Flexicore (Stryker). The Charité and ProDisc-L received FDA approval in 2004 and 2006 respectively, while Maverick and Flexicore multicenter trials have completed enrollment in their RCTs and are currently operating in continued access, nonrandomized modes. SpinalMotion (Mountain View, California), developer of the Kineflex lumbar artificial disc implant, submitted their premarketing approval application to the FDA in 2009. One of the potential barriers to using any of the disc arthroplasty devices instead of traditional fusion surgery for CLBP with advanced DDD is lack of end plate structural integrity (Figure 30-8).

Figure 30-6 Total disc arthroplasty device: Charité (Depuy).

(From Yue JJ, Bertagnoli R, McAfee PC, An HS. Motion preservation surgery of the spine. Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

Figure 30-7 Total disc arthroplasty device: ProDisc-L (Synthes).

(© Synthes, Inc. or its affiliates. All rights reserved.)

Theory

Mechanism of Action

Fusion Surgery

Kirkaldy-Willis and colleagues described a degenerative cascade involving the intervertebral discs, facet joints, and ligamentum flavum that could eventually lead to neural impingement if sufficiently severe.31 This degenerative cascade initially involves dehydration of the disc and loss of disc height that naturally occurs with aging. These changes in disc composition and morphology may lead to posterior bulging, which exerts pressure on the ligamentum flavum and pushes it toward the neural canal. Further degeneration or injury to a degenerated disc may then lead to tears in the annulus, resulting in posterior prolapse of the nucleus pulposus into the neural canal.

Impingement of the neural canal may result in neurologic dysfunction from direct or indirect causes. Spinal nerve root function may be disrupted due to direct mechanical compression, although the amount of pressure required to do this remains a matter of continued research. An alternative mechanism that has been proposed is that spinal nerve root function may be indirectly affected by chemical mediators of the acute inflammatory cascade (e.g., cytokines).32 Claudication may result from direct mechanical compression of spinal nerve roots or from focal ischemia.33

Whereas decompression surgery may alleviate neurologic dysfunction by removing one or more of the structures with degenerative changes that may be causing or contributing to impingement of the neural canal, decompression alone may not be sufficient to address an underlying etiology related to severe degeneration. Because the elimination of motion after solid arthrodesis has been effective for pain relief in other arthritic joints within the body (e.g., ankle, wrist, hip), it is no surprise that fusion surgery to eliminate excessive motion leading to segmental instability has been used to treat CLBP. However, it should be acknowledged that the precise mechanism of action by which fusion surgery may alleviate symptoms of CLBP is not completely understood. The complexity of the multiple spinal articulations and uncertainty in determining whether these joints are in fact related to the etiology of CLBP underlines the inherent challenge presented by fusion surgery when compared to arthrodesis in smaller joints with less complex movement. Some authors have previously reported that clinical outcomes obtained following fusion surgery did not correlate with the presence of a radiographically solid arthrodesis.34–36

Indication

Fusion Surgery

Fusion surgery is often used for a variety of indications. Given its primary objective, fusion surgery is most commonly used for CLBP with persistent, severe symptoms that may be due to underlying surgical instability secondary to degenerative spondylolisthesis, DDD, isthmic spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis, or failed back surgery syndrome. However, defining patients with CLBP who may be appropriate candidates for fusion surgery remains challenging because findings from the physical and neurologic examination, as well as advanced imaging or other diagnostic testing, have generally failed to identify a clear pathoanatomic cause for CLBP. This lack of consensus regarding appropriate indications has led to large geographic variations in the rate of lumbar spine surgery across the United States that cannot be explained by demographics alone.37 This uncertainty may perhaps best be illustrated by contrasting the two main schools of thought with respect to CLBP in the absence of serious spinal pathology, which are briefly discussed here.

Combined Approach

The combined approach to CLBP attempts to integrate the best elements of both approaches described above. For fusion surgery, this combined approach would first attempt to identify patients with CLBP in whom there is a high degree of certainty that instability may be responsible for their symptoms and offer them a surgical intervention. For other patients where the likelihood of long-term benefit from fusion surgery is uncertain, the combined approach would likely promote the use of multidisciplinary rehabilitation combining educational, behavioral, and exercise approaches (described elsewhere in this text) rather than recommend fusion surgery. An important consideration in this combined approach is the timing of any proposed surgical intervention. Generally, fusion surgery should not be considered for CLBP unless the patient has suffered substantial functional disability and unremitting pain for a prolonged period despite receiving appropriate conservative interventions. Although the specific definition of appropriate conservative interventions remains elusive and depends on the clinical scenario, it may be appropriate to at least consider fusion surgery for severe CLBP of more than 6 months duration if no clinically meaningful improvement is noted following a coordinated approach with analgesics, supervised therapeutic exercise, manual therapy, education, and behavioral therapy.38

Assessment

Before receiving fusion surgery or disc arthroplasty, patients should first be assessed for LBP using an evidence-based and goal-oriented approach focused on the patient history and neurologic examination, as discussed in Chapter 3. Clinicians should also inquire about medication history to note prior hypersensitivity/allergy or adverse events (AEs) with drugs similar to those being considered, and evaluate contraindications for these types of drugs. Advanced imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or CT myelography is required to help guide the spine specialist to target the appropriate spinal levels involved in a patient’s CLBP and related neurologic dysfunction. Findings on advanced imaging that may be of particular interest when considering fusion surgery include advanced degenerative changes. However, the presence of these findings on advanced imaging is not sufficient to justify proceeding with spinal surgery. It is of the utmost importance that any findings on advanced imaging be correlated with findings made independently from the medical history, symptoms, physical examination, and neurologic examination. Screening for biopsychosocial risk factors associated with poor outcomes should also be conducted before considering fusion surgery or disc arthroplasty.

Efficacy

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Fusion Surgery

The CPG from Belgium in 2006 found low-quality evidence against fusion surgery for LBP without neurologic involvement.39

The CPG from Europe in 2004 could not recommend fusion surgery for CLBP because multidisciplinary rehabilitation was shown to be as effective as fusion surgery. However, fusion surgery could be used if all other conservative treatments were unsuccessful and combined behavioral and exercise interventions are not available in the patient’s geographic area.40

Similarly, the CPG from Italy in 2007 only recommended fusion surgery if 2 years of all other conservative therapy failed and psychological prognostic factors were absent.41

The CPG from the United Kingdom in 2009 recommended fusion surgery only if the patient was in severe enough pain to consider surgery an option and all other treatments had failed including combined physical and psychological interventions.42

The CPG from the United States in 2009 found fair evidence of a moderate net benefit for fusion surgery versus standard nonsurgical therapy and fair evidence of no benefit versus intensive rehabilitation for managing CLBP without neurologic involvement.43

Disc Arthroplasty

For DDD without neurologic involvement, the CPG from the United States in 2009 found fair evidence of no difference for disc arthroplasty versus fusion surgery for up to 2 years of follow-up and insufficient evidence for longer-term outcomes.43

Findings from the above CPGs are summarized in Table 30-1.

TABLE 30-1 Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations of Fusion Surgery and Disc Arthroplasty for Chronic Low Back Pain

| Reference | Country | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Fusion Surgery | ||

| 39 | Belgium | Not recommended |

| 40 | Europe | Not recommended |

| 41 | Italy | Recommended |

| 42 | United Kingdom | Recommended |

| 43 | United States | Recommended |

| Disc Arthroplasty | ||

| 43 | United States | Insufficient evidence |

Systematic Reviews

Fusion Surgery

Cochrane Collaboration

The Cochrane Collaboration conducted an SR in 2005 on various forms of lumbar surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis.45 A total of 31 RCTs were identified, of which 19 examined the effects of fusion surgery. Of the 19 RCTs identified for fusion surgery, 4 examined CLBP, 2 examined chronic DDD, 3 examined DDD without specifying the duration of symptoms, 5 examined spondylolisthesis, 2 included a mixture of spondylolisthesis and spinal stenosis, 1 included spinal stenosis, 1 included a mixture of failed back surgery syndrome, DDD, degenerative spondylolisthesis, and isthmic spondylolisthesis, and 1 included a mixture of patients without specifying the duration of LBP or condition.35,45–61

Three RCTs examined decompression surgery alone versus decompression surgery combined with fusion surgery, and their pooled results via meta-analysis did not find any statistically significant differences between the two approaches.34,58,59 In addition, another RCT did not find any differences between fusion surgery alone versus fusion surgery combined with decompression surgery for patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis.57 One RCT observed a statistically significant improvement in pain and disability for fusion surgery versus an intensive exercise program after 2 years of follow-up for patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis.54 One RCT randomized patients to three different forms of fusion surgery or to physical therapy and observed statistically significant improvements in pain and disability after 2 years of follow-up among the groups who received fusion surgery.46 Another RCT examined the effects of fusion surgery versus a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program (including a cognitive behavioral component) and observed no statistically significant differences in pain and function.46 Two RCTs compared fusion surgery versus disc arthroplasty and observed no statistically significant differences at the end of follow-up.49,50 Eight RCTs were pooled via meta-analysis to show that fusion surgery with instrumentation improved the radiologic fusion surgery rate, while four RCTs provided inconsistent evidence about the relative superiority of different techniques for fusion surgery (i.e., anterior, posterior, circumferential).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree