KEY POINTS

Candida species are the third most frequent cause of bloodstream infections in ICUs in US hospitals and are responsible for 10% of nosocomial infections in some European ICUs.

Candida albicans is the most common cause of candidemia in ICU patients. In the last two decades in the United States, there has been a shift upward in the proportion of candidemias that are caused by other Candida species, especially Candida glabrata. The prominent Candida species in many neonatal ICUs is Candida parapsilosis.

The risk factors for invasive candidiasis include extremes of age, trauma, burns, high APACHE II score, recent abdominal surgery, gastrointestinal tract perforation, pancreatitis, mechanical ventilation, central venous catheters, parenteral nutrition, dialysis, and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.

Candiduria is common in the ICU and is mostly related to the presence of indwelling bladder catheters and broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents. The vast majority of patients who are candiduric are colonized, do not develop upper tract infection or candidemia, and do not require treatment.

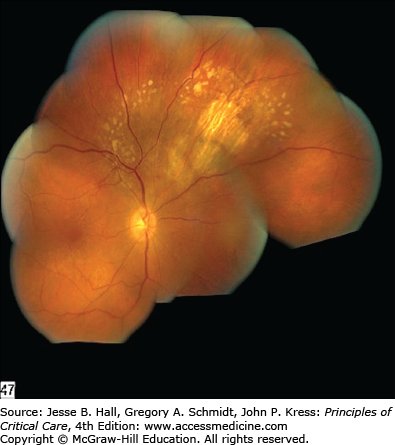

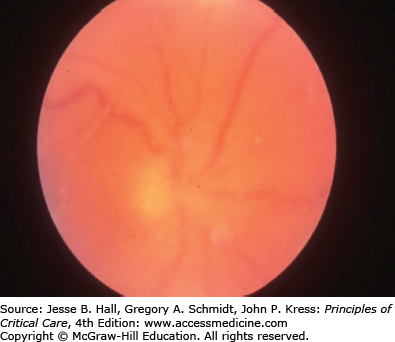

All patients who have documented candidemia should have a dilated eye examination by an ophthalmologist to determine whether metastatic infection is present in the eye.

All patients with documented candidemia should be treated with an antifungal agent. Prompt treatment of candidemia significantly decreases the mortality rate, and delay for 24 hours or more after the blood culture is taken is associated with increased mortality.

In an ICU in which C glabrata is a commonly isolated organism, initial treatment should be with an echinocandin. If the ICU historically has had few infections caused by C glabrata, initial treatment shoud be with fluconazole. After the organism has been identified, therapy should be switched to the most appropriate agent.

Removal of central venous catheters in patients with candidemia leads to more rapid clearing of the organism from blood and improved outcomes.

Prophylaxis against invasive candidiasis with fluconazole could be considered in ICUs that have rates of candidemia that exceed 10%; it should not be used in most ICUs.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive fungal infections are an increasingly prevalent problem in hospitalized patients, especially those in intensive care units (ICU).1-9Candida species cause more than 90% of fungal infections in the ICU setting. Candida species are the third most frequent cause of bloodstream infections in ICUs in US hospitals and are responsible for 10% of nosocomial infections in some European ICUs.1,4 The reasons for the increase in invasive Candida infections in ICU patients include the expanding numbers of immunocompromised patients, longer survival in the ICU of patients who have multiple medical problems, increased use of devices and invasive procedures that disrupt the host’s natural barriers to infection, and the adverse effects of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents on the normal human microbiota.

Far less frequent are infections due to Aspergillus species, but there are increasing reports of invasive aspergillosis in nonneutropenic patients in the ICU.10,11 Occasional patients who have endemic mycoses, such as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, or non-Aspergillus mold infections, such as mucormycosis, are cared for in the ICU, but these infections will not be addressed in this chapter. The main focus will be on invasive Candida infections.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF FUNGAL INFECTIONS IN THE ICU

Candida species are part of the normal human microbiota. Most infections are due to those strains of Candida that have colonized the gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, or skin of the patient.5,9 Colonization with Candida is a prerequisite for subsequent infection except in those rare circumstances in which exogenous introduction of Candida species has occurred.12,13 Disruption of the gastrointestinal mucosa, as occurs during surgery or with chemotherapy-induced ulcerations, in concert with broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents, allows overgrowth of the patient’s own commensal Candida strains and subsequent egress to the bloodstream.5,14 In addition, Candida that exists on the skin can enter the bloodstream directly by ingress along an indwelling intravenous catheter.15 Less commonly, candidemia is due to Candida originating from the genitourinary tract, and then almost always in the setting of obstruction.16 Rarely, if ever, are Candida species colonizing the oropharynx responsible for invasive infection and candidemia.17

Uncommonly, outbreaks of Candida infections have been linked to transmission from the hands of health care workers, especially those who have onychomycosis or onycholysis or those who wear artificial nails.12,18-20Candida parapsilosis, the predominant species that colonizes hands, is the species most often associated with outbreaks, but other species have also been implicated.21

Candida albicans remains the most common cause of candidemia in ICU patients2,5,6,9,22 (Table 70-1). In the last two decades, increasing numbers of ICUs in the United States have reported a shift upward in the proportion of candidemias that are caused by other Candida species.22-28 In some tertiary care centers, nearly 50% of candidemias now are caused by non-albicans Candida species.28 The most prominent species to emerge in the United States is Candida glabrata.5,22,29,30 Although many hospitals in Europe report a picture similar to that seen in the United States, others have few candidemias due to C glabrata.2,31 Most hospitals in South and Central America report very few cases of C glabrata infection and many more infections due to C parapsilosis and Candida tropicalis.32 Additionally, several studies have confirmed that C glabrata is an uncommon cause of infection in children, but becomes an increasingly important pathogen in older adults.25,29 Medical centers that treat many patients with hematological malignancies report higher rates of isolation of C glabrata and Candida krusei.33 This is due, in part, to increased use of fluconazole in these centers.34

Candida Species Causing Infection in ICU Patients

| Species | Comments |

|---|---|

| Candida albicans | Most common species; susceptible to fluconazole; can treat with fluconazole or echinocandins |

| Candida glabrata | Increasingly found in ICUs, especially those with heavy fluconazole use; MICs high and many isolates resistant to fluconazole; more common in older adults; echinocandins preferred treatment |

| Candida parapsilosis | More common in neonatal ICUs; susceptible to fluconazole; most common central venous catheter–associated species; low mortality rates; higher MICs to echinocandins; fluconazole preferred treatment |

| Candida tropicalis | More common in cancer patients; susceptible to fluconazole; high mortality rates |

| Candida krusei | More common in cancer patients; resistant to fluconazole; echinocandin preferred; high mortality rates |

| Candida lusitaniae | Uncommon species; resistant to amphotericin B; fluconazole preferred treatment |

| Candida guilliermondii | Uncommon species; higher MICs to echinocandins; fluconazole preferred treatment |

| Candida dubliniensis | Uncommon species; similar to C albicans; susceptible to fluconazole |

The prominent Candida species in many neonatal ICUs is C parapsilosis, and this organism is especially likely to colonize central venous catheters.21,22Candida tropicalis is prominently noted in cancer patients.9,33 Other species, such as Candida lusitaniae, Candida guilliermondii, and Candida dubliniensis, are uncommon causes of candidemia and invasive candidiasis.35

The risk factors for invasive candidiasis are many and include extremes of age, trauma, burns, high APACHE II score, recent abdominal surgery, gastrointestinal tract perforation, pancreatitis, mechanical ventilation, central venous catheters, parenteral nutrition, dialysis, and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy2,4,7,9,22,29,36-38 (Table 70-2). A large prospective multicenter study in the United States that evaluated risks for candidemia in over 4000 patients admitted to surgical ICUs found that prior surgery, acute renal failure, parenteral nutrition, and central venous catheters were independently associated with increased risk for developing candidemia.22 Another multicenter study in Spain noted that the independent risk factors for development of candidemia were sepsis, prior surgery, parenteral nutrition, and Candida colonization at multiple sites.2

Risk factors for Candidemia and Invasive Candidiasis

|

The risks of infection with non-albicans Candida species include those noted above for Candida in general, but also include prior exposure to antifungal agents.27,28 For C glabrata, risk factors include older age, recent abdominal surgery, use of multiple antibiotics, and receipt of parenteral nutrition.29,30,38 Among cancer patients who had C tropicalis fungemia, the independent risk factors included leukemia and prolonged neutropenia.39 Patients with C krusei candidemia have been noted to be more likely to have had prior exposure to antifungal agents, have a hematologic malignancy or a stem cell transplant, have neutropenia, and have been treated with corticosteroids.33

CLINICAL DISEASE CAUSED BY CANDIDA SPECIES

A variety of different organ systems can be involved with invasive candidiasis (Table 70-3). Forms of candidiasis other than candidemia are less well defined. A common problem that arises in the ICU is how to determine invasive disease in the abdomen, the urinary tract, and the respiratory tract. The presence of Candida in cultures from these sites may reflect colonization, which is extremely common in these sites, or may be an indicator of invasive infection. These sites have a rank order for the likelihood of invasive candidiasis, with intra-abdominal infections being the most common, urinary tract infections the next most common, and respiratory tract infections, rare. Uncommon sites of Candida infection, such as endocarditis, meningitis, and osteoarticular infections, will not be discussed here.

Types of Systemic Illnesses Caused by Candida Species in ICU Patients

|

Candidemia is simply defined as the presence of Candida species in the blood. It is the most studied syndrome caused by Candida because it is easily defined and the end points for success are clear-cut. Candidemia can be an isolated event, or it can be a herald for disseminated infection involving multiple organs. Candidemia can culminate with sepsis, but many patients, especially those with an indwelling central venous catheter, may be merely febrile with no localizing signs. Conversely, patients can have invasive candidiasis, but not be candidemic.

Intra-abdominal infections with Candida species most often occur secondary to bowel perforation, anastomotic leaks after bowel surgery, and acute necrotizing pancreatitis.40,41 Peritonitis and/or abscess formation can occur, and sepsis may ensue. C albicans is most often found, but in some medical centers, C glabrata predominates. The symptoms of intra-abdominal infection due to Candida do not differ from those seen with bacterial pathogens, and in fact, mixed bacterial-yeast infections are the rule.

The diagnosis is made when peritoneal fluid or abscess material obtained by ultrasound or CT-guided aspiration or at the time of surgery yields Candida species. Growth of yeast from an indwelling drain is not adequate for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal Candida infection because it usually reflects only colonization of the drain.

Candiduria is common in the ICU; this is mostly related to the presence of indwelling bladder catheters and broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents.42 The vast majority of patients who are candiduric are colonized and do not develop upper tract infection or candidemia. In one large prospective series in a general hospital setting, of 861 patients who had candiduria, only 7 became candidemic.43 With obstruction, however, pyelonephritis and subsequent fungemia can ensue.16 Further diagnostic studies, such as ultrasound and/or a CT urogram, are often needed to assess hydronephrosis and the presence of fungus balls.44 Several studies have noted an increase in mortality in patients who are candiduric, but this is believed to be a marker for significant underlying illnesses and cannot be attributed to Candida urinary tract infection.44,45

Pneumonia due to Candida species is rare. When pulmonary involvement does occur, it is secondary to hematogenous spread in markedly immunosuppressed patients.17 Infection is usually manifested as multiple nodules throughout the lung field; lobar infiltrates are uncommon. Sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage samples that yield Candida species have low specificity, and lung biopsy is needed to establish the diagnosis. In a prospective study of 232 ICU patients who died with pneumonia and underwent autopsy, none of 77 patients with Candida species isolated from a tracheal aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid had histopathologic evidence of Candida pneumonia.46 As is true of candiduria, respiratory tract colonization with Candida species is associated with increased mortality in ICU patients, likely reflecting the severity of underlying illnesses.47

OUTCOMES OF INVASIVE CANDIDA INFECTIONS

Invasive candidiasis is associated with a high mortality rate.3,22,23,48-52 Crude mortality rates as high as 71% have been reported.49 For many patients, invasive candidiasis is a marker for serious underlying illness, but is not the cause of death. Attributable mortality has been difficult to evaluate, and estimates have varied from 30% to 62%.3,49 A recent prospective observational study in French ICUs found that independent factors associated with mortality from invasive candidiasis included diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and mechanical ventilation,52 whereas a study that included all hospitalized patients in four medical centers in Sao Paulo, Brazil, found the highest risk factors were advanced age and high APACHE II score.51 The association of a high APACHE II score and increased mortality in patients with candidemia has been noted by others,23 as has increased mortality with increasing age.38 Several studies have shown that prompt treatment of candidemia significantly decreases the mortality rate, and delay for as long as 48 hours after the blood culture is performed is associated with increased mortality.53,54

Mortality appears to be higher in patients with candidemia due to C krusei, but this could reflect the fact that this species is seen more often in patients who have hematological malignancies.27,33 Mortality associated with candidemia due to C parapsilosis is consistently lower than that found with other species.23,51 In some studies, mortality rates for patients who have C glabrata fungemia have been noted to be higher than that seen with C albicans,27 but in other studies, there was no difference or the rates were lower.23,29,55

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of invasive candidiasis requires clinical suspicion that Candida infection could be present. The patient might be only mildly ill or may have sepsis. Many of the manifestations of invasive candidiasis and candidemia do not differ from those seen with bacteremia and other serious bacterial infections, and patients, especially those with an intra-abdominal process, can have polymicrobial infection with yeasts and bacteria.

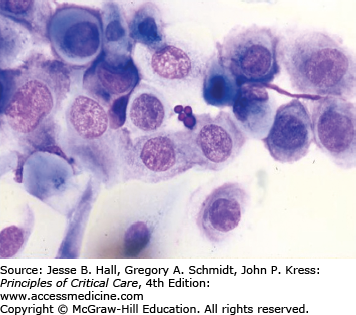

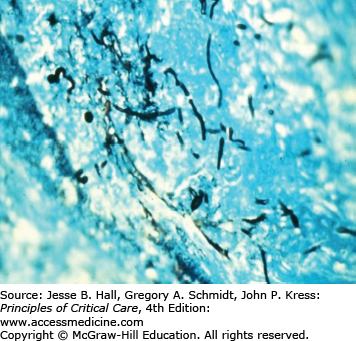

Several findings can help point one toward a diagnosis of candidemia. Skin lesions can occur on any area of the body. The lesions are usually nontender, nonpruritic pustules on an erythematous base. They may be tiny, looking similar to folliculitis, with little erythema, or the erythema can extend for a centimeter around the lesion (Figs. 70-1 and 70-2). Biopsy of these lesions reveals budding yeasts and sometimes both yeast and hyphal forms typical for Candida (Figs. 70-3 and 70-4).

Findings in the retina can also lead one to a diagnosis of candidemia although most often the retinal findings are prompted by an ophthalmological examination after blood cultures have yielded Candida species. The major symptom is visual loss; however, patients in the ICU often cannot complain of changes in visual acuity. Chorioretinitis appears as white spots on the retina that are distinctive enough to be considered diagnostic when seen by an ophthalmologist (Fig. 70-5). Vitreal extension of the infection causes worsening vision, and the ophthalmological examination reveals inflammatory changes in the vitreous and markedly abnormal visual acuity (Fig. 70-6). In patients in whom blood cultures yield Candida, a retinal examination by an ophthalmologist is strongly recommended, as the treatment regimen will change if endophthalmitis is documented.

Culture of blood has sensitivity for yielding Candida species of only 50% to 60%, based on data using older methods for culturing blood. Using current automated systems, the yields are improved, but no analysis has been done to accurately assess the sensitivity of these systems in an ICU population at risk for candidiasis.56,57

Because Candida species are part of the microbiota of humans, growth of this organism from mucous membranes, abdominal drains, and sputum merely documents colonization with Candida species.17Candida pneumonia can only be diagnosed by finding tissue invasion in lung biopsy material, and not from culture of respiratory secretions.17 In most patients, candiduria represents colonization of the urinary tract, and further studies are necessary to establish a diagnosis of Candida urinary tract infection.44 On the other hand, culture of Candida species from normally sterile sites, characteristic skin lesions, and involved tissues implies invasive infection.

It takes 1 to 3 days for yeasts to grow in blood culture bottles and for the laboratory to notify the clinician of this event. In most laboratories, subculture onto solid media is required to determine the species of Candida, adding an additional few days until a final identification is reported. Several studies have shown increased mortality when antifungal therapy is delayed more than 48 hours after blood is taken for culture.53,54 An increasing number of laboratories use a rapid specific fluorescence-based assay, PNA-FISH, that can identify C albicans and C glabrata within 1 to 2 hours of finding yeasts in a blood culture bottle.58,59

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree