Forensic Examination of Adult Victims and Perpetrators of Sexual Assault

Judith A. Linden

Annie Lewis-O’Connor

M. Christine Jackson

Sexual assault is a crime of violence, which often goes unreported yet frequently has prolonged physical and emotional effects on victims. Statistics from the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS), a telephone survey of 8,000 men and 8,000 women, reported a 17.6% lifetime prevalence of rape among women (1 of every 6) and a 3% prevalence rate among men (1 of every 33) (1). The National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) reported a sexual assault victimization rate of 0.8 per 1,000 persons aged 12 or older (2). Stated another way, a person is sexually assaulted every 2.5 minutes in the United States (3). In 1992, 16% of reported rape victims were younger than 12 (and therefore not captured in the NCVS) (4). According to the NVAWS, 3.6% of women were raped as a child, 6.3% as an adolescent, and 9.6% as an adult. Among men, 1.3% were raped as a child, 0.7% as an adolescent, and 0.8% as an adult (1). Many rapes go unreported: according to the NVAWS, only 19% of women and 13% of men who were raped after their 18th birthday reported the crime to the police (1).

Women are not convinced that reporting a sexual assault will lead to the conviction of the perpetrator. In fact, many women believe that their trauma after a sexual assault will be exacerbated if they take legal action. The 1993 Senate Judiciary Committee Report titled “The Responses to Rape” stated that 84% of reported rapes do not result in conviction (5). Of the 16% of perpetrators convicted, half are sentenced to less than 1 year in prison and 4% are not incarcerated at all (5). The NVAWS confirms this, with 46% of prosecuted rapists convicted but only 76% sentenced to jail or prison; therefore, only 13% of rapes reported to police result in incarceration (1). The sense of not being able to obtain justice from the legal system is one of the many consequences for all victims of rape. Other rape-related sequelae include posttraumatic stress syndrome, depression, eating disorders, substance abuse, and suicide (1,6,7,8,9). The tangible, out-of-pocket cost of sexual assault (excluding child sexual abuse) is estimated at $3.3 billion per year (10). For each rapist who is not convicted, there are usually subsequent victims because rapists tend to be repeat offenders. A rapist who has been caught has, on average, 14 previous victims (11). Appropriate conviction and incarceration of a rapist constitute justice served for the current victim and all prior victims; in addition, the rapist’s future victims are spared.

When evaluating a victim of sexual abuse/assault, the emergency physician must not only meet strict legal standards but also provide complete medical care and emotional support. A preestablished systematic approach enables the busy emergency physician to complete an adult sexual assault examination adequately. Proper collection of evidence provides medical care for the victim as well as hope for legal recourse against the perpetrator.

Physicians who perform sexual assault evidentiary examinations must be familiar with the related legal aspects for their particular region. They must know the definition of rape and sexual assault as well as the legal time limits for evidence collection. The rights of the victim must be understood, and ensured, prior to obtaining consent for and proceeding with an evidentiary examination. To ensure the legal validity of evidence, sound procedures must be employed when collecting evidence and the chain of custody must be maintained. Failure to maintain this chain means that the collected forensic evidence can be thrown out of court, resulting in profound devastation for a victim. Because many cases depend on the forensic evidence, maintaining the chain of custody can make or break a case.

Definition of Rape

Earlier definitions of rape typically included an act of forced vulvar penetration by a penis, object, or body part without the consent of a woman, during which ejaculation may or may not occur. This definition limits rape to women. During the past decade, many states have changed the definition to include both genders, now defining rape as an act of forced penetration of an orifice by a penis or object without a person’s consent. Some states have addressed the problem of male rape by using the term sexual assault to broaden the coverage of unwanted sexual acts to include rape, sexual abuse, and sexual misconduct involving either gender. Sexual assault includes sexual contact of one or more persons with another without appropriate legal consent. The definition of rape and sexual assault varies slightly from state to state; although many states define rape in gender-neutral language, some states retain gender-specific language. The examiner needs to be familiar with the local jurisdiction’s definitions of rape and nonconsensual sexual acts.

Time Limits

In the past, the usual legal time limit for the collection of evidence was 72 hours from the time of the assault. However, recent updates in DNA analysis and sperm survival data have led some programs to extend the time limit up to 120 hours or 5 days. Victims of sexual assault presenting to a medical institution within the local jurisdiction’s established specified time frame should be assigned priority in triage along with other serious emergencies, as the evidentiary examination must be conducted without delay to minimize loss or deterioration of evidence as well as immediate psychological trauma. If more than 120 hours have passed since the assault, a complete physical examination should still be conducted to examine for injuries to the body and the genitalia, to offer treatment to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and to provide information for support resources. Depending on the local sexual assault protocol, a modified evidentiary examination may be indicated. On the basis of the spermatozoa survival data, there may be value in collecting cervical samples even when the patient presents more than 72 hours after the assault (12).

Consent/Maintaining Chain of Evidence

To protect the rights and interests of both the patient and the hospital, an appropriate signed written consent must be obtained before beginning the examination, treatment, and evidence collection. The consent form for the evidentiary examination is in the standard sexual assault evidence-collection kit. Evidence collection is never medically necessary, and it is important to know that items removed from the patient must be transferred to the police in the rare event of a warrant. In addition, body cavity searches for evidence are not medically necessary. When there is unexplained vaginal bleeding, it is medically necessary to find a cause but it is not necessary to collect evidence. When a patient signs a consent form, it means that she or he understands that evidence will be collected, preserved, and released to law enforcement authorities. Consent for the evidentiary examination includes consent for obtaining photographs of physical trauma to be used as evidence in a court of law (some jurisdictions have a separate consent form for photographs). A signed written consent for the sexual assault evidentiary examination does not replace the general consent for routine diagnostic and medical procedures that are standard with emergency treatment and done in accordance with hospital policy.

The patient may consent to an examination and/or treatment and/or evidence collection. In some states, the collection of evidence mandates a report to law enforcement officials. In other states, evidence may be collected without being reported, for a designated period of time, after which the evidence kit is destroyed if the sexual assault is not reported. When the local law enforcement agency is notified, the agency will render a complaint number and send an investigative officer to the hospital to interview the victim and generate a report. Even if the patient does not want to make a police report or have an evidentiary examination, the local enforcement agency may need to be notified to implement local procedures. In all states, the rape of minors, adults who are mentally challenged or disabled, and the elderly is subject to mandatory reporting; however,

laws regarding mandatory reporting of adult victims vary from state to state (13).

laws regarding mandatory reporting of adult victims vary from state to state (13).

When obtaining signed written consent for a sexual assault examination and evidence collection, the physician must inform the patient of his or her rights. The patient has the right to decline any or all parts of an examination that entails evidence collection. The patient needs to be made aware that evidence deteriorates over time and may be unobtainable if it is not collected and preserved promptly. In some states, evidence can be collected and the victim is given a specified period within which to report. The physician must explain that the collected body fluids and swabs may lead to the identification of the offender, especially in the light of DNA “fingerprinting” techniques and the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) (see Chapter 13). The patient must also be informed that consent for the evidence-collection examination, once given, can be withdrawn at any time for all or part of the procedure. The patient has the right to decline the collection of reference/baseline specimens, such as pulled hair strands, blood for DNA profiling, and oral swabs.

If the patient declines to have reference samples collected at the time of the examination, it may be done at a later date. The reference specimens allow the crime laboratory to conduct a comparative analysis of the evidence in question. Patients should be informed that head hairs change over time if they are braided or dyed or if certain medicines are taken (e.g., chemotherapy).

Patients have the right to know if they are responsible for the cost of the examination. If an evidentiary examination is performed, the local government is responsible for its cost. The cost of the medical examination and treatment is the patient’s responsibility (in some states [e.g., Iowa], the costs may be covered, even if a legal report is not made). Testing and treating for STIs and prophylaxis against pregnancy may also be provided without charge. Programs that do not do baseline testing for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) should give the patient appropriate referral information.

To maintain the chain of custody, careful and proper handling and transfer of the collected evidence are crucial. Documentation should clearly state who collected the evidence, who picked up and transported the evidence, and that it was stored appropriately and securely. A retrospective study of sexual assault evaluations performed by emergency physicians and ob-gyn residents in an urban emergency department (ED) revealed that the chain of custody was documented properly in only 6% of cases (14).

Preservation of the chain of custody is crucial to ensure that the evidence is not altered, destroyed, or lost before trial. All documentation of evidence transfers must include the following information: the name of the person transferring custody, the name of the person receiving custody, and the date and time of transfer. Transfers should be kept to a minimum, ideally limited to two persons. The evidence-collection kit is turned over to law enforcement officers by the examiner after the examination has been completed and the reference samples, swabs, and slides have been dried completely. If this is not possible, the evidence must be stored in a locked area accessible only to designated individuals. Materials that need to be refrigerated (i.e., blood and urine samples) must be locked in a refrigerated area. If some materials are still drying when the officers need to leave, a note to the crime laboratory should indicate that drying is in progress. When blood and urine collections are refrigerated, it is helpful to store the logbook in a plastic bag along with the blood. The plastic bag protects the book from spills and makes it easy to find.

The Adult Sexual Assault Patient (Females and Males)

Patient Intake

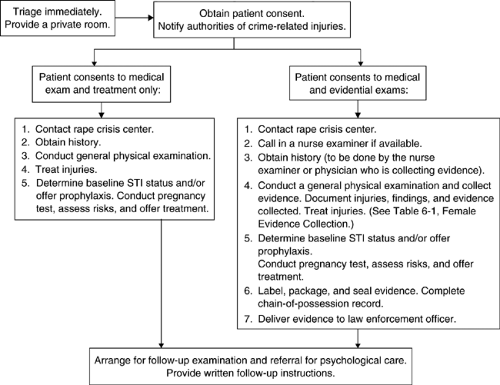

When a person who has been sexually assaulted comes to an ED within 120 hours after the assault, she or he should be triaged quickly, assessed for stability, and escorted promptly to a private area for the initial assessment. The triage, consent, and examination process for females is diagrammed in Figure 6-1, and the evidence-collection process is delineated in Table 6-1. The examination should be conducted without delay to minimize the loss or deterioration of evidence. A trained support person should be assigned to each victim. A patient who is taken directly to an examining room should, preferably, not change into a hospital gown until her/his clothing has been collected properly. If the patient desires evidence collection, then the protocols designated in the evidence-collection kit should be implemented. If the victim wants to report the assault, the police should be notified. In some states, the sexual assault response team (SART) is activated from triage. Law enforcement will then generate a complaint number specific to the victim. In some states, notification of police is mandatory (13).

The examiner should carefully explain the process of the examination to the patient. After the patient has been informed of her/his rights and agrees to the examination, a written consent for the examination is obtained before proceeding. The examiner should obtain the history in a nonjudgmental, warm, and professional manner,

realizing the emotional challenge the victim faces when recounting the details of the assault.

realizing the emotional challenge the victim faces when recounting the details of the assault.

Medical Screening Examination

On arrival, the sexual assault victim needs to be assessed for unstable vital signs and must be medically and psychologically cleared before the initiation of the evidentiary examination. The clinician should determine whether there has been a change in mental status or whether there is a history of loss of consciousness. The patient should be examined to rule out serious medical/surgical injuries (including tears of the rectouterine pouch). Complaints of moderate to severe pain should alert the examiner to possible serious injuries. A review of fatal sexual assaults revealed that the most common causes of death are mechanical asphyxiation, beating, lacerations, drowning, and gunshot wounds (15). Fatal injuries are sustained by 0.1% of women who are sexually assaulted (16). Five percent to 10% of survivors of sexual assault sustain major nongenital injuries (16).

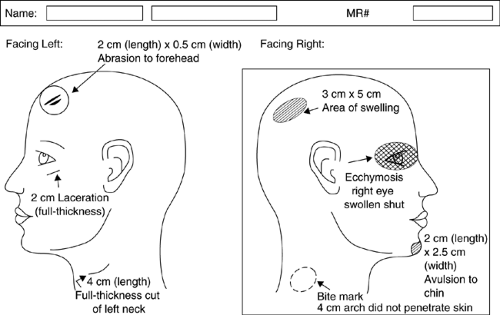

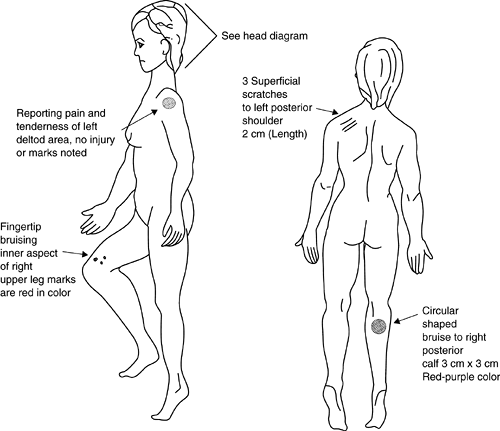

In addition to the standard trauma survey, the physician also needs to search carefully for evidence of physical injuries inflicted by the perpetrator during the assault. Findings can be documented and described on a head and/or body diagram (Figs. 6-2 and 6-3.) Studies conducted during the past two decades have found that 31% to 82% of sexual assault victims sustain physical injuries (17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26), most often involving the head, face, neck, and extremities (17,19,24). Although the incidence of injuries is significant for all ages and types of victims, women younger than 50 and nonpregnant women are more likely to be physically injured during sexual assault (17,24). The risk of sustaining physical injuries also increases if the assailant was a stranger (26,27,28). The lack of evident physical or genital trauma does not imply consent by the victim or the absence of rape (21) (Appendix 6-1).

Slapping, kicking, beating, and biting are methods the perpetrator employs to overcome the resistance of the victim. The victim’s entire body must be thoroughly examined for areas of tenderness, soft-tissue swelling, abrasions, contusions, bruises, petechiae, bite marks, lacerations, fractures, and other evidence of violence. Areas of tenderness without bruising should be documented carefully using body map or photographs. Bruises may develop 1 to 2 days later and can be photographed on follow-up examinations.

The back of the head may be banged against the ground during a sexual assault; therefore, soft-tissue swelling and lacerations may occur. The history regarding the events related to the sexual assault

is crucial in guiding the examination and evidence collection. Another cause of scalp hematoma or soft-tissue swelling is violent pulling of the hair (29). Head trauma, specifically basilar skull fracture, may present as raccoon eyes or Battle’s sign. If the victim experienced loss of consciousness, the Glasgow Coma Scale score should be determined at triage. A complete ophthalmic examination and evaluation of the tympanic membranes are indicated in cases of head trauma. Further evaluation for intracerebral

trauma by computed tomography scan must be considered. With blunt trauma to the head and face, associated injury to the cervical spine should be considered. Victims of sexual assault often sustain facial injuries, including mandibular fractures, nasal fractures, other facial fractures, broken or loose teeth, facial lacerations, and ocular trauma. The breasts should be examined for evidence of trauma, including contusions, lacerations, swelling, and bite marks. If the assailant pulls and twists the victim’s clothing, then petechial hemorrhages or a line of punctate bruising may occur on the skin, commonly in the area of the bra strap or near the axilla (29).

is crucial in guiding the examination and evidence collection. Another cause of scalp hematoma or soft-tissue swelling is violent pulling of the hair (29). Head trauma, specifically basilar skull fracture, may present as raccoon eyes or Battle’s sign. If the victim experienced loss of consciousness, the Glasgow Coma Scale score should be determined at triage. A complete ophthalmic examination and evaluation of the tympanic membranes are indicated in cases of head trauma. Further evaluation for intracerebral

trauma by computed tomography scan must be considered. With blunt trauma to the head and face, associated injury to the cervical spine should be considered. Victims of sexual assault often sustain facial injuries, including mandibular fractures, nasal fractures, other facial fractures, broken or loose teeth, facial lacerations, and ocular trauma. The breasts should be examined for evidence of trauma, including contusions, lacerations, swelling, and bite marks. If the assailant pulls and twists the victim’s clothing, then petechial hemorrhages or a line of punctate bruising may occur on the skin, commonly in the area of the bra strap or near the axilla (29).

Table 6-1 Collection of Evidence From Female Victims of Sexual Assault (Expansion of Step 4 in Evidential Examination [Fig. 6-1]) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The extremities should be inspected for evidence of the perpetrator’s attempts to overcome the resistance of the victim. Fingernail abrasions; fingertip injuries; and bruises on the wrists, ankles, and inner/outer aspects of the arms and thighs (defense injuries) are sustained during the assailant’s attempts to restrain the victim. If the perpetrator forcibly twisted the victim’s wrists, erythema and point tenderness in that area may be noted (29). A careful search for patterns of injury during inspection may reveal injuries that are not readily apparent from the initial history. If the assailant overwhelmed the victim and held her/him in restraint, then bruises and abrasions may be seen over bony prominences.

Once the trauma survey has been completed and the patient medically cleared, then a careful search for patterns of injury and evidence collection is initiated. Physical examination of the sexual assault victim focuses on the detection of physical (nongenital) injuries and genital injuries. The incidence of genital injuries varies from 6% to 65%, with most investigators reporting a range between 10% and 30% (17,18,19,20,21,23,24,25,26,30,31). Elderly female victims of sexual assault (age 60 to 90 years) have a 43% to 52% increased incidence of genital trauma, double that of sexual assault victims younger than 60, and their injuries are often more serious (owing to decreased or lack of estrogenation) (24,25). The most common sites of injury do not differ among victims younger or older than 50 (23). Genital injury may be more prevalent in nonpregnant victims (21% vs. 5%) (17). One must always be cognizant that lack

of abnormal findings does not indicate that a sexual assault did not occur (32).

of abnormal findings does not indicate that a sexual assault did not occur (32).

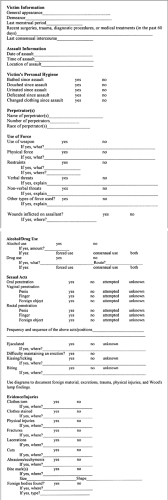

Victim Interview

It is best to begin the history taking with less invasive, general questions, such as medical and surgical history, use of medications, and drug allergies. These should have been documented in the medical chart. There is controversy over whether drug or alcohol use within the previous 120 hours should be documented, but this may be important, as it may help establish lack of consent. Positive toxicologic test results for alcohol or drugs are not uncommon and the examiner should not allow the results to place the victim’s history in question (17,33). Information about anal-genital injuries sustained during the past 60 days as well as surgeries, diagnostic procedures, or medical treatment performed within that period should be documented to prevent confusion with injuries related to the sexual assault. The interview should focus on items that fulfill the legal criteria of rape, including penetration of an orifice, lack of consent, and threat or actual use of force, as well as identification of the assailant and witnesses, if possible. All recorded information is admissible in court.

The physician should document the following information (Fig. 6-4):

The name, age, sex, and race of the victim

The patient’s vital signs

The date, time, location, and/or physical surroundings of the assault, including odors; any witnesses

The patient’s personal hygiene (e.g., showered, bathed, brushed) since the assault

The name(s), number, race(s), and any other identifier(s) of the perpetrator(s), if known

The use of weapons, physical force, restraints, injuries, forced drug or alcohol use, and verbal and/or nonverbal threats

The threats, types of force, or other methods used by the perpetrators(s) (including drug-facilitated assault) and the area(s) of the body affected

The sexual acts committed by the perpetrator(s); the sexual acts the victim was forced to perform on the perpetrator(s)

Details regarding the attempt to penetrate or actual penetration of the oral cavity, vagina, or rectum by penis, finger, or object and the resultant injuries

Whether the victim recently inserted tampons or any other foreign objects into her own orifices

The frequency and sequence of the sexual acts

Positions used during the assault

Whether the assailant ejaculated and the location

The use of a condom or lubricant

If there was more than one assailant, which perpetrator committed which act

Whether kissing, biting, or licking occurred and the site(s) involved

A careful history must be taken, as some victims may be reluctant to describe all the acts committed, particularly anal penetration. The patient should be asked if she/he remembers injuring the assailant during the assault (e.g., by scratching or biting). Questions related to the sexual assault should be open ended (e.g., “And what happened next?”). The examiner should not ask leading questions.

Any physical injuries, sites of bleeding, and/or areas of pain described by the victim must be recorded. Injuries occurring before and independent of the assault should be identified (e.g., fractured arm, lacerations, or bruising), with clarification of all findings. If the assault occurred within 120 hours of the examination, the victim’s personal hygiene activities since the assault should be noted because this information affects the laboratory analysis of evidence. The physician should ask patients if they have bathed, douched, urinated, defecated, brushed their teeth, or vomited since the assault. The date of a female victim’s last menstrual period should be documented to determine whether she is menstruating at the time of the examination, to evaluate the possibility of pregnancy and to consider emergency contraception. If the patient had consenting intercourse within the past 120 hours, the approximate date and time should be recorded. This information is required by the crime laboratory because it can affect the analysis of the evidence.

Physical Examination

The patterns of injury associated with sexual assault result from restraining methods used by the perpetrator, the violent acts of the perpetrator, as well as the victim’s attempt to defend her/himself. Despite evidence that sexual assault does not result in visibly detectable physical or genital injury in all cases, the criminal justice system still relies on physical evidence of trauma to convict a perpetrator. The examiner needs to be knowledgeable of forensic medicine pertaining to sexual assault to detect physical injury, document trauma, and collect evidence appropriately, all of which may increase the chances of a successful legal outcome (18,34,35). (Sexual anatomy terminology is presented in Appendix 6-2.)

Some sexual assailants use threatening behavior with guns, knives, or other weapons to overcome the resistance of the victim (36). Some use only

verbal threats. Regardless of resistance efforts, the assailant’s use of a weapon and/or force usually overcomes the victim (37). Cartwright retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 440 female sexual assault survivors to identify factors that correlated with injury. The risk of physical injury was greatest if the assailant’s weapon was a knife or club (79%) rather than a gun (34%). If no weapon was employed, the incidence of physical injury fell between that associated with use of a knife/club and a gun (27). The patient may or may not sustain an injury from the weapon itself. The weapon may be used as a threat and the physical trauma inflicted in a different manner. The patient’s history will usually guide the physician toward the detection of such injuries.

verbal threats. Regardless of resistance efforts, the assailant’s use of a weapon and/or force usually overcomes the victim (37). Cartwright retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 440 female sexual assault survivors to identify factors that correlated with injury. The risk of physical injury was greatest if the assailant’s weapon was a knife or club (79%) rather than a gun (34%). If no weapon was employed, the incidence of physical injury fell between that associated with use of a knife/club and a gun (27). The patient may or may not sustain an injury from the weapon itself. The weapon may be used as a threat and the physical trauma inflicted in a different manner. The patient’s history will usually guide the physician toward the detection of such injuries.

In certain circumstances, the victim may attempt to resist the assailant’s attack and sustain “fight,” or defense, injuries related to that effort. The victim may have contusions of the forearms or the legs, caused by self-defense movements. Injuries on the hands, especially the knuckles, can also reflect self-defense actions. If the victim was dragged over

a rough surface, she/he may have longitudinal abrasions on the limbs or trunk. Dirt particles may be embedded in the skin. The victim’s fingernails may be broken if she/he scratched the assailant or defended herself/himself during the attack. The victim’s clothing may have been torn during attempts to resist the assault (28).

a rough surface, she/he may have longitudinal abrasions on the limbs or trunk. Dirt particles may be embedded in the skin. The victim’s fingernails may be broken if she/he scratched the assailant or defended herself/himself during the attack. The victim’s clothing may have been torn during attempts to resist the assault (28).

The amount of resistance by the victim is affected by many variables, one of which is fear instilled by the assailant’s verbal threats and/or threats with weapons. A victim held at gunpoint is less likely to have injuries associated with resistance. Although there is some consensus that resistance increases the chance of aborting rape, it is inconclusive whether the victim’s physical resistance alters the risk of being physically injured (16,37). The risk of physical injury correlates with the assailant’s aggression, not with more forceful resistance by the victim (38).

Evidentiary Examination

A full evidentiary examination includes collecting clothing; debris; samples from under the patient’s nails; pubic and scalp hair samples; reference blood; swabs from the skin, sites of injury (bite marks), and bodily orifices; and control swabs. Before collecting evidence, the examiner should moisten a set of control swabs with the same vial of sterile water used to moisten the evidence-collection swabs. Saline should not be used to moisten the swabs because it can destroy DNA evidence. The sterile water vial becomes the control. After the swabs dry, they should be returned to the sleeve and placed in an envelope labeled as such. Some kits come with “control swabs.” In this case, controls need not be prepared.

Collection of Clothing

After arrival at the ED, the patient should remain clothed until it is time to conduct the examination, if possible. Once a patient consents to evidence collection, the steps delineated in the evidence-collection kit should be followed. A thorough history of the sexual assault should be obtained (see the bulleted list under Victim Interview on page 92). The patient’s general appearance and demeanor should be documented objectively. Along with the vital signs, the patient’s height, weight, and color of eyes and hair should be noted. Once evidence collection begins, the examiner should wear gloves to prevent DNA contamination. The patient’s clothing should be observed for rips, tears, odors, stains, and other foreign materials, including fibers, hair, twigs, grass, soil, splinters, glass, blood, and seminal fluid. Before the patient’s clothing is collected, it should be scanned for fluorescent exudates (using a Wood’s lamp), and positive areas should be noted in the examination report. All clothing worn during and immediately after the assault should be collected and labeled and its collection should be documented (Table 6-1). If the victim is not wearing the clothing worn at the time of the assault, then only the items that are in direct contact with the victim’s genital area need to be collected. The police officer in charge should be informed to arrange for collection of the clothing worn at the time of the assault.

The proper method of collecting the clothing is to have the patient stand on two sheets of clean paper on the floor, one sheet on top of the other. The disposable paper placed routinely on examination tables can be used for this process. The purpose of the bottom sheet of paper is to protect evidence on the clothing from being contaminated by debris or dirt on the floor. The top sheet is submitted to the crime laboratory. The patient should remove her/his shoes prior to stepping on the paper for disrobing to avoid contamination of loose trace evidence with nonevidential debris from the shoe soles. The shoes should be collected and packaged separately. The victim’s clothing should not be shaken, because microscopic evidence could be lost. Holes, rips, or stains in the victim’s clothing must not be disturbed by cutting. In the case of a ligature, the knot should not be untied (see the explanation in the next section).

Skin Survey

A thorough head-to-toe skin surface survey must be conducted. The skin should be searched grossly for evidence of bleeding, lacerations, abrasions, bruises, erythema, edema, scratches, bite marks, burns, stains, moist and dried secretions, and foreign materials. Different patterns of trauma are associated with an assailant’s efforts to stop the victim from screaming: clamping the hand over the mouth, use of adhesive materials over the mouth, gagging. The mouth and lips must be inspected for evidence of trauma or residual adhesive material. Marks of brute force or strangulation should be sought. The presence of ligature marks, bruises, abrasions, or scratches on the neck should be noted. Swabbing these areas for DNA using a wet and then a dry swab has led to an increase in DNA findings. Gagging and strangulation both lead to asphyxia and may result in physical evidence, such as scattered petechial hemorrhages over the face and the eyelids. Subconjunctival hemorrhages and retinal hemorrhages may also result from attempted strangulation (29,39).

The perpetrator may have used ligatures or tape (e.g., duct tape) to restrain the victim. If ligatures are still in place, the entire ligature and its placement (including the knot) should be photographed before its removal. Then the ligature can be cut away

from the knot, taking care not to destroy the knot, which may be a signature of the assailant. The physical signs of restraint, usually on the ankles and/or wrists, vary and depend on the tightness, resistance, and the length of time the victim was restrained. The patterned abrasion or bruise at the site of the restraint may range from tenderness to slight erythema of the skin to a deeper skin lesion with distal edema (29).

from the knot, taking care not to destroy the knot, which may be a signature of the assailant. The physical signs of restraint, usually on the ankles and/or wrists, vary and depend on the tightness, resistance, and the length of time the victim was restrained. The patterned abrasion or bruise at the site of the restraint may range from tenderness to slight erythema of the skin to a deeper skin lesion with distal edema (29).

With the lights darkened in the room, the entire body should be scanned with a long-wave ultraviolet light (Wood’s lamp/Bluemaxx light), searching for fluorescent exudates. The ultraviolet light reveals evidence of dried or moist secretions, stains, fluorescent fibers, and subtle injuries (such as rope marks and contusions) not readily visible in white light. If findings are noted, their location, size, and appearance should be documented in the text and on the schematic figures of the body. Photographs of the skin trauma should be taken. If photographs are to be taken of injuries that are visible only in ultraviolet light, the examiner may want to rely on local crime laboratory experts. Photographic documentation of these subtle injuries requires a longer exposure time and the use of a stationary tripod in a darkened room. Photographs of bruises may be helpful in defining the object that inflicted the injury (patterned injury).

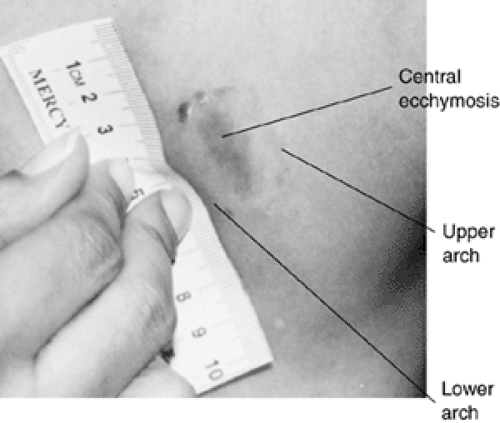

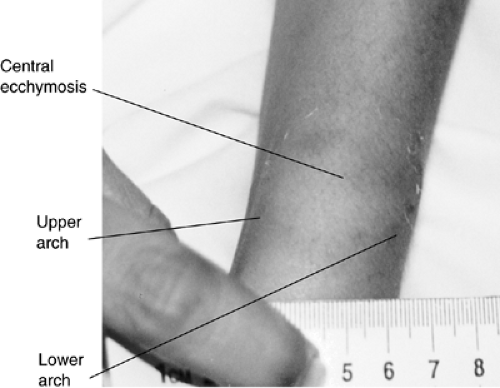

With the proper technique, photographs of bite marks assist in identifying the perpetrator. If the bite mark has broken or perforated the skin, the creation of a cast by a forensic odontologist, if available, may be indicated. This evidence can be compared with court-ordered impressions and wax bites from the suspect. A typical human bite mark is a round or oval ring-shaped lesion with two opposing, often symmetric, U shapes with open spaces at the bottom. The intensity of force behind the bite affects the pattern depth and characteristics (i.e., the pattern may have abrasions, contusions, or lacerations in the area of the teeth) (40) (Figs. 6-5 and 6-6, see color plate). The classic bite mark shape is not always present, so if a bite mark is suspected, then forensic evaluation of the lesion is indicated. In documenting the bite mark, the site, size, shape, color, and type of injury are noted (e.g., contusion with ecchymosis, abrasion, laceration, incision, avulsion, petechial lesion). Findings such as smooth skin or indentation of the skin by teeth should be noted. If the patient gives a history of being bitten in a certain area but tenderness is the only physical sign noted, the clinician must remember that bruises and bite marks may not be apparent immediately following an assault but can develop later. A recommendation should be made to the police to arrange for a follow-up examination and additional photographs by the crime laboratory after the bruising has developed more fully. Serial photographs have been recommended by law enforcement and should be taken for 6 days at 24-hour intervals, because bruises and bite marks become more evident with time.

Fig. 6.5 Bite mark on the breast (see color plate). |

The perpetrator’s saliva and residual epithelial cells on bite mark wounds should be collected using the two-swab technique for the collection of dried secretions. The outside border of the bite mark should be swabbed toward the center of the bite mark, first with the wet swab, then the dry one. Some local protocols specify the use of two moist swabs together. The greatest amount of saliva is usually deposited in the area of the bite mark caused by the lower teeth. Both swabs must be allowed to dry thoroughly, the wet swab for at least 1 hour. Then both swabs are submitted for the forensic analysis of DNA.

Collection of Foreign Material

Along with textual, diagrammatic, and photographic documentation, evidence on the patient’s body (e.g., foreign materials, dried and moist secretions, and stains) should be collected properly. Foreign materials include fibers; hair; grass; dirt; and thicker stains of semen, saliva, or blood. A separate “miscellaneous” envelope should be used for each location on the body from which foreign material is collected. The envelope should be labeled with the term “debris” and the materials and the site of collection should be noted. The separate foreign material envelopes are sealed and placed in the main miscellaneous evidence-collection envelope. Location of the foreign material should be recorded in the text and marked on the diagram. For the collection of foreign materials, a tweezer, a glass slide, or the dull side of a scalpel blade can be used to gently loosen or scrape the foreign substance onto the opened and flat miscellaneous paper collection

envelope. Sometimes the use of a cotton-tipped swab moistened with sterile water can be helpful. The paper envelope should be refolded in a manner to retain the scraping and debris. If heavily crusted semen or blood is found on the pubic hair, the matted hairs bearing the specimen should be cut out and placed in a collection envelope, which is then labeled and sealed.

envelope. Sometimes the use of a cotton-tipped swab moistened with sterile water can be helpful. The paper envelope should be refolded in a manner to retain the scraping and debris. If heavily crusted semen or blood is found on the pubic hair, the matted hairs bearing the specimen should be cut out and placed in a collection envelope, which is then labeled and sealed.

Fig. 6.6 Bite mark on the wrist (see color plate). |

If the victim gives a history of scratching the assailant or if foreign material is observed under the nails, fingernail scrapings should be collected, as they may contain blood and/or tissue of the perpetrator or other evidence from the crime scene. The right- and left-hand collections are performed as separate procedures. Most sexual assault examination kits provide the two fingernail scrapers and the collection envelopes required for the procedure. Each of the victim’s hands should be held over an unfolded, flat collection paper. Then scrapings are taken from under all five fingernails and the debris is allowed to fall onto the paper. The used scraper is placed in the center of the paper, which is then refolded to retain the debris and the scraper and placed in a labeled envelope. The two envelopes are identified as containing “right-hand fingernail scrapings” or “left-hand fingernail scrapings.” The nails may also be swabbed using a cotton swab moistened with sterile water.

Evidence specimens of thin secretions and stains from blood, semen, and saliva need to be collected properly to improve the forensic yield when they are subjected to genetic typing tests, most importantly DNA testing. The method of collecting evidence from moist secretions or stains differs from that involving dried secretions or stains. Both methods use swabs supplied in the sexual assault evidence kit. If the number of swabs is not sufficient, a sterile cotton-tipped swab can be used. Each suspicious moist or dried secretion, stain, or fluorescent area needs to be approached as a separate procedure with separate swabs and labeled in detail. When bloodstains are present, the stain pattern should be photographed before the evidence is collected. The area is swabbed, and injuries that might be associated with the blood should be noted.

The two-swab technique is used for dried secretions or stain areas noted on the gross visualization examination and with the light-scanning procedure (41). The first swab is moistened with sterile distilled water and then used to swab the evidence area. When wetting the swab with sterile water, one drop should be used, if possible, rather than saturating the swab. The amount of moisture applied to the swab can be controlled by using a 10-mL syringe into which distilled water has been drawn. This technique is generally adequate for obtaining the specimen and facilitates drying in a timely manner. Both swabs must be dried thoroughly—the wet swab for at least 1 hour with either a stream of cool air or on a drying rack. The second swab is left to dry and is used to swab the same site as the wet swab. Once the wet swab has dried, both swabs from one evidence site are packaged together in the original wrapper. The wrapper is labeled with the evidence-collection site and placed in the main miscellaneous evidence-collection envelope. If evidence is collected from a moist area of secretion or stain, a dry swab is used to avoid dilution of the evidence. The swab is allowed to air-dry for at least 1 hour and is then placed in a labeled envelope or tube, which is then sealed. If the swabbed area (moist or dried) was found with the use of a Wood’s lamp, “W.L.” should be marked on the envelope. The findings are recorded, and the locations of the secretions or stains are noted in the text and on the diagram of the body.

Sometimes a hand or arm print will show up on the Wood’s lamp examination. It is important to swab and document these areas because they may contain epithelial cells from the assailant.

Sometimes a hand or arm print will show up on the Wood’s lamp examination. It is important to swab and document these areas because they may contain epithelial cells from the assailant.

Dried semen stains have a characteristic shiny, mucoid appearance and tend to flake off the skin. Under an ultraviolet light, semen usually exhibits a blue-white or orange fluorescence and appears as smears, streaks, or splash marks. Because freshly dried semen may not fluoresce, each suspicious area should be swabbed, whether it fluoresces or not, with a separate swab. Not all fluorescent areas observed under ultraviolet light are indicative of seminal fluid; therefore, forensic confirmation of the findings is necessary.

Reference Samples

Reference samples, including blood and head and pubic hair, are collected to determine whether the specimens are foreign to the patient. They are also used for comparison with specimens from potential suspects. Plucking of hairs from the patient’s head permits the evaluation of hair length as well as the variation of natural pigment or hair dyes from the root to the tip of the strand. Patients should be given the option of pulling out their own hair reference samples, as this gives them the feeling of having more control over the situation. A minimum of five full-length hairs should be pulled from each of the following scalp locations (total of 25 hairs): center, front, back, left side, and right side. The hairs should represent variations in length and color. They are placed in an envelope, which is labeled and sealed. (If a patient has attached synthetic hair, samples of both the synthetic hair and the real hair should be collected, and a notation made on the outside of the collection envelope that both have been included.)

Reference samples of pubic hair can be collected simultaneously with the pubic hair evidence collection. A sheet of paper should be placed beneath the patient’s buttocks. The pubic hair is combed forward from the mons pubis toward the vaginal area first, to remove any loose hairs or foreign materials that may have transferred from the assailant to the patient during the assault. The loose hairs, foreign materials, pubic hair, and comb are placed in the sheet of paper, which is then folded with the contents inside. The folded paper and its contents are placed in a large labeled envelope, which is then sealed. Then, samples of the patient’s pubic hairs are needed for comparison with the suspect’s hairs. The patient or the examiner needs to pluck at least 10 to 15 hairs of various lengths and color from the pubic area (42). The hairs can be compared microscopically, and if hairs foreign to the victim are identified, they can be tested utilizing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) DNA. (Some crime labs request that the hairs be plucked later, when requested by laboratory personnel.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree