Forensic Emergency Medicine

29-1 Identification of Wounds: Shotgun Wounds

Robert Hendrickson

Clinical Presentation

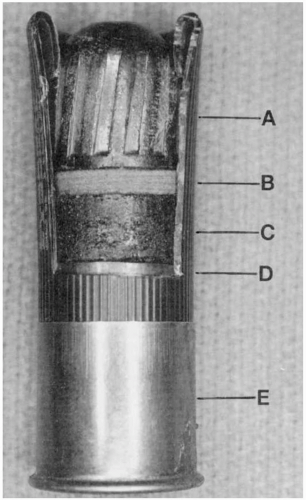

Shotguns are capable of producing a variety of wounds, depending on the ammunition used. Ammunition may be “buckshot,” or lead shot, which are multiple, small lead pellets. Lead shot produces entrance wounds that vary in appearance depending on the distance between the gun and the target.1 Close-range wounds produce a single, large defect and may have a rectangular contusion from the plastic cup that holds the shot.2 Intermediate-range wounds have a central defect with surrounding lead shot wounds. Long-range wounds produce multiple smaller wounds from individual shot as the shot separates in the air. Shotguns may also be fired with a single slug, or “wad.” Wounds from single slugs may appear similar to other gunshot wounds, but with a potentially greater diameter.2

Pathophysiology

As lead shot leaves the barrel of a shotgun, it begins to separate secondary to resistance and gravity. At close range, the shot projectiles travel as a tightly packed group and may produce tissue injury that is similar to that caused by a single, large projectile. As distance from the target increases, the shot separates and produces tissue injury that is more similar to the impact of smaller, individual projectiles. Lead shot injuries rarely cause exit wounds, because the original muzzle energy is divided many times and is essentially dissipated among the individual shot projectiles.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by clinical recognition of the typical injury pattern.

Management

Treatment of shotgun injuries is similar to that of other penetrating trauma; however, lead shot may produce injury over a larger surface area than individual projectiles do.1,2

REFERENCES

1. DeMuth WE Jr. The mechanism of shotgun wounds. J Trauma 1971;11:219-229.

2. Gestring ML, Geller ER, Addak N, Bongiovanni PJ. Shotgun slug injuries: case report and literature review. J Trauma Infect 1996;40:650-653.

29-2 Identification of Wounds: Blunt Weapon

Robert Hendrickson

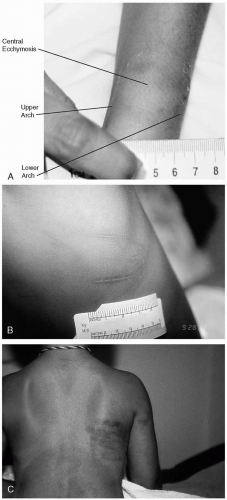

Blunt traumatic injuries may produce pattern abrasions, contusions, or lacerations that mimic the striking object.1 Examples of a pattern abrasion are marks left by a fingernail, carpet, or teeth. Lacerations are produced by blunt force and may reflect the shape of the object. Pattern contusions are the most common pattern injury. Blunt injury from a cylindrical weapon typically leaves a linear, central clearing flanked by parallel contusions. Finger impressions typically appear as circular or oval contusions and may be grouped linearly in the shape of a hand. In addition, contusions may resemble the shape of the offending weapon (e.g., belt, electric cord, hand). Contusion formation and resolution are highly variable. Numerous factors influence the dating of contusions, including the amount of blunt force and tissue characteristics, vascularity, and density.2 Bite marks typically appear as two curvilinear contusions or abrasions, or both. Bite marks should be treated with great care, because they may contain evidence as to the identity of the assailant. Bite marks should be swabbed with a sterile cotton applicator that has been moistened in sterile saline or water.1 The sample should be sent to a crime laboratory for identification of DNA and blood group antigen.1

REFERENCES

1. Smock WS. Forensic emergency medicine. In: Olshaker JS, Jackson MC, Smock WS, eds. Forensic emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

2. Wilson EF. Estimation of the age of cutaneous contusions in child abuse. Pediatrics 1977;60:750-752.

29-3 Identification of Wounds: Sharp Weapon

Robert Hendrickson

Injuries caused by sharp weapons fall into two categories: incised wounds and stab wounds.1 Incised wounds are caused by the drawing of a sharp weapon across the skin, which results in a broad, shallow wound with regular edges. Stab wounds are deeper than they are wide. Stabs wounds may or may not reflect the weapon that produced the wound. Single-edged knives may produce a wound with one sharp edge and one blunt edge, whereas double-edged knives may produce two sharp edges. However, these rules are not always accurate. A single-edged knife can produce two dull edges if the knife was “hilted,” with the base of the knife contacting the skin. “Hilted” knives can also produce bruising around the stab wound from the hand of the perpetrator. In addition, wounds may be “V”- or “C”- shaped if the weapon was twisted while in the body.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree