FOREIGN BODY: INGESTION AND ASPIRATION

AUN WOON SOON, MD AND SUZANNE SCHMIDT, MD

Through play, experimentation, and daily activities, children are likely to place foreign bodies just about anywhere. Once an object or foodstuff is in a child’s mouth, it can lodge in the nasopharynx, respiratory tract, or be ingested. According to the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System, more than 110,000 foreign-body exposures were reported in the United States in 2012, and of these, 88% occurred in the pediatric population. Young children, age 6 months to 4 years, are at an increased risk for foreign-body aspiration or ingestion due to their inquisitive nature and tendency to explore objects with their mouths. Often, a “choking episode” will clear the foreign body; however, serious sequelae of an aspirated object can range from an acute life-threatening event to a slowly evolving pneumonia. The severity of an ingested foreign body is determined by the nature of the object (e.g., blunt, long, sharp, battery, magnetic) and its location in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Generally, most ingested foreign material is well tolerated, and may pass unnoticed by the family and child.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

There are three main pathophysiologic considerations for aspirated and ingested foreign bodies: the anatomic determinants of lodgment site, the physical properties of the foreign body (size, shape, and composition), and the local tissue reaction to the foreign body.

The respiratory tract gradually narrows distal to the larynx, whereas the GI tract has several sites of anatomic or functional narrowing. An ingested foreign body may lodge in three distinct esophageal sites, may be unable to pass through the pylorus, or may become impacted in the duodenum, appendix, ileocecal valve, rectum, or any other location of congenital or acquired narrowing.

The nature of the foreign body (size, shape, and composition) and the ability of the tissue to distend influence the site of lodgment within the respiratory or GI tract. Depending on the location in the airway, an aspirated object may minimally, intermittently, or completely impede airflow. The composition of the foreign body also determines the local tissue reaction and the evolution of complications. A button battery can erode through the esophageal wall rapidly compared with the slow tissue reaction to a coin. In the bronchial tree, the fatty oils in some aspirated foods (e.g., peanuts) create a more severe inflammatory reaction than a similarly sized nonorganic object. While the ingestion of a single blunt magnet may cause little problem, the ingestion of more than one can lead to magnetic attraction across bowel walls, resulting in bowel necrosis, perforation, or volvulus.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Gastrointestinal Foreign Body

Esophagus

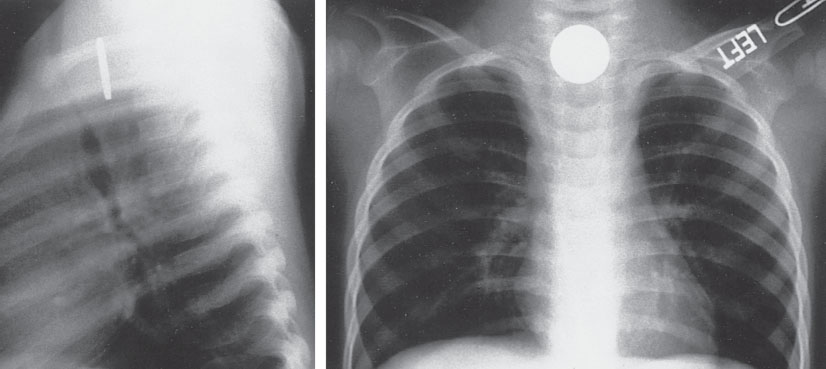

The esophagus is the most common site of lodgment for an ingested foreign body and may have serious complications. Most childhood esophageal foreign bodies are round or spherical objects, with coins accounting for 50% to 75% of these (Fig. 27.1). This contrasts with adults, whose impacted esophageal foreign bodies tend to be foodstuffs (meat) and bones (e.g., fish or chicken), and are often associated with underlying conditions of the esophagus (e.g., strictures, dysmotility, extrinsic compression). Most children with esophageal impactions have a structurally and functionally normal esophagus. Children with acquired esophageal strictures (e.g., secondary to caustic ingestions) or repaired congenital conditions (e.g., esophageal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula) are at increased risk for recurrent esophageal impactions, including foodstuffs (e.g., hot dogs, chicken).

Foreign bodies of the esophagus tend to lodge at three sites. The thoracic inlet (Fig. 27.1) is the most common location, accounting for 60% to 80% of esophageal foreign bodies. The next most common sites are the gastroesophageal junction (10% to 20%) and the level of the aortic arch (5% to 20%). The level of lodgment in children with underlying esophageal conditions depends on the location of the constricting lesion.

Foreign bodies that remain lodged in the esophagus may lead to potentially serious complications including respiratory distress, upper airway compromise, esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and aortic or tracheal fistula formation. Therefore, it is imperative that the physician consider the possibility of esophageal foreign bodies, especially in young children 6 months to 4 years of age.

Stomach and Lower Gastrointestinal Tract

Objects that pass safely into the stomach generally traverse the remainder of the GI tract without complication. Safe passage has been documented in hundreds of cases involving various foreign objects, including sharp objects such as screws, tacks, and staples. This may not be true in the younger child when long (greater than 5 cm) objects are unable to negotiate the turns and may become impacted in the duodenum and ileocecal region. However, no definitive age or length guidelines exist. This also may not be true of some very sharp objects (e.g., bones, needles, pins) that may perforate the hollow viscera, resulting in peritonitis, abscess formation, or hemorrhage.

FIGURE 27.1 Two-view chest radiograph demonstrating impacted esophageal coin located at the thoracic inlet.

Respiratory Foreign Body

Upper Airway

Foreign bodies that lodge in the upper airway can be immediately life-threatening. According to the National Safety Council, choking was the fourth leading cause of unintentional injury death in the United States in 2007. In 2009, 4,600 deaths were reported from unintentional ingestion or inhalation of food or objects that resulted in airway obstruction. Most children with aspirated foreign bodies are younger than 3 years of age. The most common foods responsible for fatalities include hot dogs, candy, meat, and grapes. Childhood fatality from aspiration of manmade objects is less common. These objects tend to be conforming objects, with balloons, small balls, and beads accounting for most cases. Children with foreign bodies in their upper airways may present with acute respiratory distress, stridor, or complete obstruction of their upper airway. In patients with complete airway obstruction, emergency treatment depends on proper application of basic life-support skills. Back blows and chest compressions are used in infants, and the Heimlich maneuver is used in toddlers, children, and adolescents while the patient remains conscious. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be initiated if the patient becomes unresponsive. If these methods fail to dislodge the foreign body, rapid progression to direct visualization and manual extraction or an emergency airway is necessary (see Chapters 3 Airway and 4 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation).

Lower Respiratory Tract

Childhood foreign bodies of the lower tracheobronchial tree represent a diagnostic challenge due to the ubiquitous nature of the presenting symptoms (e.g., cough, wheezing, respiratory distress), the frequency of the asymptomatic presentation, and the potential for false-negative and false-positive screening radiographs.

Foreign bodies of the lower respiratory tract occur more commonly in young children, with a slight propensity to lodge in the right lung (52%). Organic matter accounts for 81% of aspirations, with nuts and seeds (sunflower and watermelon) being the most common, followed by other food products (apples, carrots, and popcorn), plants, and grasses. Plastics and metals make up a minority of aspirated objects (Fig. 27.2), and coin aspiration has rarely been reported.

The diagnosis of lower airway foreign-body aspiration is often delayed due to nonspecific symptoms, and these patients may be incorrectly diagnosed with an asthma exacerbation, pneumonia, or bronchiolitis. One study found the classic clinical triad for an aspirated foreign body (cough, focal wheeze, and decreased breath sounds) was present in only 14% of patients. The most common symptoms were persistent cough (81%), difficulty breathing (60%), and wheezing (52%). A history of a witnessed choking event is highly suggestive of acute aspiration with a sensitivity of up to 93%. It is therefore important to inquire about a choking history because this is a crucial clue to diagnosis.

EVALUATION AND DECISION

Unknown Location

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree