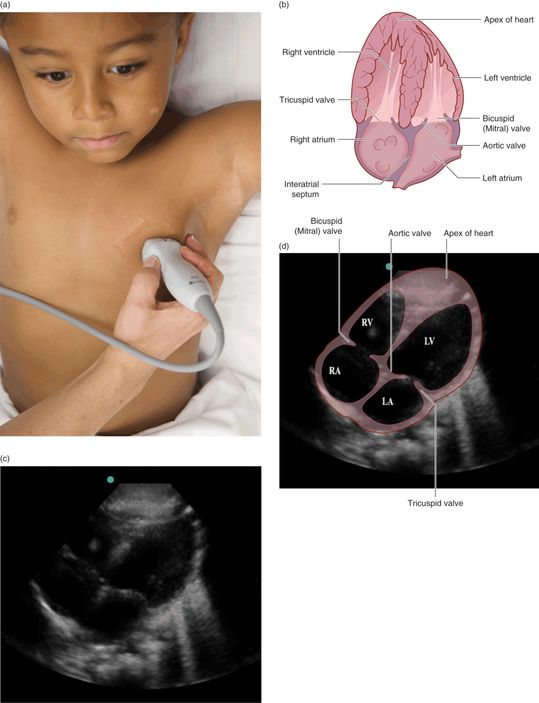

Figure 5.1 Anatomy of the heart. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press.

Technique

Point-of-care questions

Transducer selection and orientation

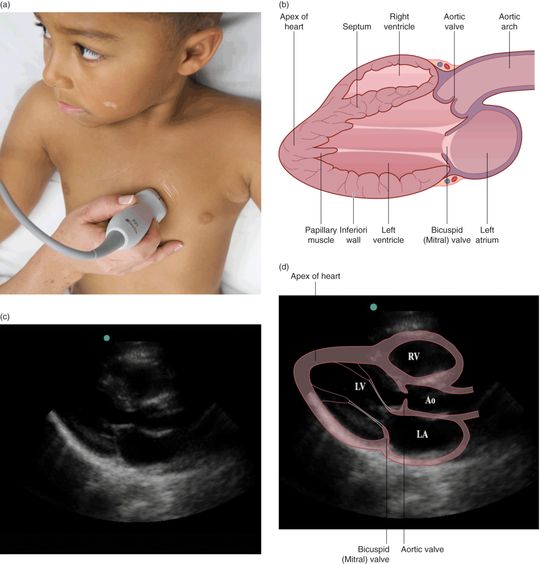

Low-frequency transducers should be utilized for the cardiac assessment. A 2–5 MHz phased-array or microconvex transducer with a small footprint is most often used in order to allow for imaging between ribs. For smaller children and neonates, a higher frequency (4–8 MHz) microconvex transducer is often required (Figure 5.2). While there is much controversy surrounding transducer orientation, emergency ultrasonographers often suggest utilizing the abdominal setting on the machine to avoid confusion. It is important to note that the “cardiac” settings on machines flip the image on the screen. Therefore, in order to create a screen image that is consistent with formal echocardiography and cardiologists, the indicator needs to be rotated 180° in relation to those transducer positions traditionally used by cardiologists. To complicate matters further, pediatric cardiologists flip the image vertically in order to most closely mirror the patient’s anatomy, which is especially useful in complex congenital heart disease (Figure 5.3d). This is not routinely recommended in the emergent and critical care settings.

Figure 5.2 Microconvex and phased–array transducers (2–8 MHz), ideal for point-of-care cardiac ultrasonography. Note the small footprints, which can easily scan in between rib spaces. The transducer on the left is a higher-frequency (2–8 MHz) microconvex transducer, while the one on the right is the phased-array transducer.

Figure 5.3 (d) Subxiphoid view, pediatric cardiologist‘s view. The image is flipped both horizontally and vertically, in order to most closely mirror anatomic orientation in the body. This is the apical four-chamber view.

Patient position and preparation

When approaching a pediatric patient in particular, positioning and patient comfort are paramount. Smaller children often require more preparation and patience. Measures to improve patient comfort and compliance with examinations include: warmed gel, lying in the parent’s lap, and pacifiers or feeding during the examination. Since children have much smaller and superficial structures than adult patients, it is important to adjust the depth of the images accordingly.

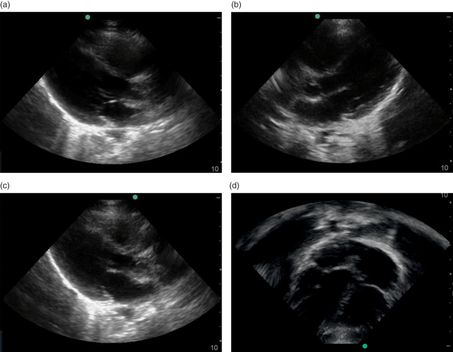

Ultrasound imaging: views

Standard views for point-of-care, focused cardiac ultrasound include subxiphoid, parasternal long-axis, parasternal short-axis, and apical four-chamber views. Angling and tilting of the transducer may be necessary in order to obtain proper images (Figure 5.4). It is important to note that all abnormal findings should be confirmed with multiple cardiac views. Additional assessments involve IVC measurements for pre-load and hydration status (see Chapter 7).

Figure 5.4 Moving the transducer. In order to obtain adequate cardiac windows, it is often necessary to rock and tilt the transducer.

Subxiphoid view

The subxiphoid view is the preferred view in the EFAST examination, and is the most useful during resuscitation, since it does not typically interfere with resuscitation and procedures. The indicator should be oriented to the patient’s right side and is placed subcostally, just below the xiphoid process, directing the indicator towards the patient’s left shoulder (Figure 5.5a). The transducer itself is quite flat (Figure 5.5b), and should be held at a 15° angle to the patient’s body, in contrast to most other positionings which are perpendicular to the patient’s body.

Figure 5.5 Cardiac imaging, subxiphoid view. (a) The transducer is oriented with the indicator towards the patient’s right, slightly angled towards the patient’s left shoulder. (b) The transducer is placed relatively flat against the patient, at approximately a 15° angle to the patient’s body. (d) Ultrasound image of the subxiphoid view. (e) The liver is shown anteriorly. The most anterior structure is the right ventricle (RV). The left ventricle (LV), right atrium (RA), and left atrium (LA) are easily visualized. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press.

The subxiphoid view utilizes the liver as an acoustic window and readily visualizes all four chambers of the heart (Figure 5.5c–e). It is the most accurate in identifying pericardial effusions, especially at the posterior pericardium where effusions begin to develop. It may be difficult to obtain in obese patients or patients with abdominal distension.

Parasternal long-axis view

The parasternal long-axis view is the preferred view for the assessment of left ventricular contractility, and the identification of pericardial effusions when adequate subxiphoid images cannot be obtained. The transducer is placed perpendicular to the chest wall, immediately to the left of the sternum, between the third and fourth intercostal space, above the level of the nipple line. The indicator should be directed towards the patient’s left hip, or 4 o’clock (Figure 5.6a). A distinguishing feature is that the aortic outflow tract is stacked on top of the left atrium (Figure 5.6a–d).

Figure 5.6 Cardiac imaging, parasternal long-axis view. (a) The transducer is placed just lateral to the sternum and is oriented with the indicator oriented towards the patient’s left hip, or 4 o’clock and perpendicular to the patient’s chest wall (b) Illustration demonstrating the corresponding anatomy. Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT); left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT); aortic valve (AV); mitral valve (MV). (c) Ultrasound image of the parasternal long-axis view. (d) Left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), aortic outflow tract (Ao), and left atrium (LA). Note that, in the parasternal long-axis view, the right atrium is not visualized. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press.

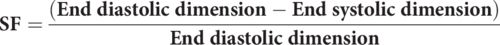

The parasternal long-axis view is best utilized to measure contractility. The left ventricular shortening fraction (SF), which is expressed as a percentage, may be calculated by the formula:

A normal calculated shortening fraction is greater than 30%. In a review of methods of sonographically determining LV function, McGowan et al. reported that visual estimation of cardiac function into normal mild, moderate, or severe dysfunction is as good or better than other more complex, calculated methods.

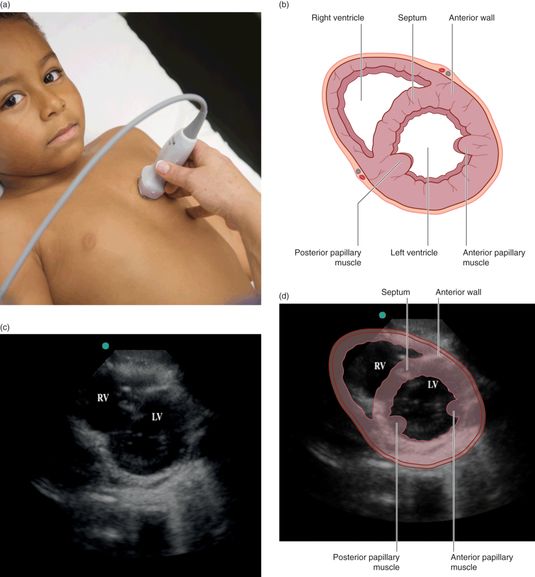

Parasternal short-axis view

The parasternal short-axis view readily allows evaluation of contractility and valvular function. Once the parasternal long-axis view is obtained, the transducer should be rotated 90°, in order to obtain the parasternal short-axis view. The indicator should be directed towards the patient’s right hip, or 7 o’clock (Figure 5.7a). One can sweep the transducer from the base of the heart to the apex in order to visualize various levels of the heart in cross-section, from the level of the mitral valve, papillary muscles, and tricuspid valve. The distinguishing feature of the parasternal short-axis view is that the left ventricle (LV) is circular, with a valve in the middle, resembling a “fish-mouth” or “doughnut” (Figure 5.7b–d).

Figure 5.7 The parasternal short-axis view. (a) The transducer is oriented with the indicator towards the patient’s right hip, or 7 o’clock. This is a 90° rotation from the parasternal long-axis view. (b) Illustration depicting the anatomy seen in the parasternal short-axis view. (c) Ultrasound image of the parasternal short-axis view, which is also known as the “doughnut” or “fish-mouth” view. (d) Illustration demonstrating the corresponding anatomy. Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press.

Apical four-chamber view

The apical four-chamber view is the preferred view for evaluating the relative dimensions of the right and left sides of the heart. The transducer is placed at the cardiac apex, which may be located by palpating the point of maximal impulse (PMI). This is typically located at the T4–5 level, at the fifth intercostal space, just lateral to the nipple. The indicator is typically oriented towards the patient’s right side, or 9 o’clock (Figure 5.8a). The patient often needs to be rotated to their left side in order to bring the heart more anterior to the chest wall, and to decrease artifact associated with the left lung. In the apical four-chamber view, all four chambers may be visualized and compared for overall size and function (Figure 5.8b–d).

Figure 5.8 The apical four-chamber view. (a) The transducer is placed lateral to the sternum, oriented with the indicator towards the patient’s right side. In teenage and adult patients, the apical four-chamber view is usually located more laterally at the nipple line. (b) Illustration depicting the anatomical structures seen in the apical four-chamber view. (c) Ultrasound image of the apical four-chamber view. (d) Illustration demonstrating the corresponding anatomy: right ventricle (RV), left ventricle (LV), right atrium (RA), and left atrium (LA). Artwork created by Emily Evans © Cambridge University Press.

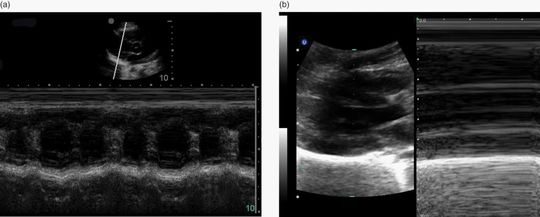

Ultrasound imaging: M-mode

M-mode, or motion mode, allows for a one-dimensional tracing of structure movement over time. While in the parasternal long-axis view, the cursor may be placed over the walls of the left ventricle, in order to assess for contractility (Figure 5.9a). This is the most effective method for evaluating for asystole (Figure 5.9b). It is important to note that, while performing this assessment to assess for cardiac contractions, compressions and artificial respirations must be held in order to avoid motion from external sources other than from the ventricle.

Figure 5.9 M-mode. When the cursor is placed over the left ventricular walls, cardiac contractions are plotted on the one-dimensional representation of motion. (a) Normal cardiac activity on M-mode. (b) The absence of cardiac contractions, or asystole, on M-mode.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree