Focal Neurologic Complaints: Evaluation of Nerve Root and Peripheral Nerve Syndromes

Amy A. Pruitt

Primary physicians are frequently asked to evaluate complaints of focal numbness, tingling, weakness, pain, or some combination of these. In general, major acute neurologic disease is not an issue during an office visit. Nevertheless, the broad range of outpatient problems encountered encompasses lesions throughout the nervous system. The primary physician should be able to localize focal complaints to the central or peripheral nervous system and to segregate those cases that must be referred to a neurologist. Accurate physical diagnosis can save thousands of dollars in unnecessary testing, such as the “pan-scan” magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) when the examination suggests a peripheral nervous system process or electromyographic testing in settings in which it is unlikely to be high yield (sensory neuropathies) or used too early (acute radiculopathy). This chapter focuses on workup and management of common upper and lower extremity nerve root syndromes and distal peripheral neuropathies followed by a section on treatment of painful peripheral neuropathy.

Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Initial Management

Many peripheral nerves, because of their superficial location, are easily injured mechanically, and others are vulnerable because of specific anatomic variants or because of alterations in anatomy caused by degenerative disease.

Upper Extremity Syndromes

Cervical Radiculopathy and Myelopathy.

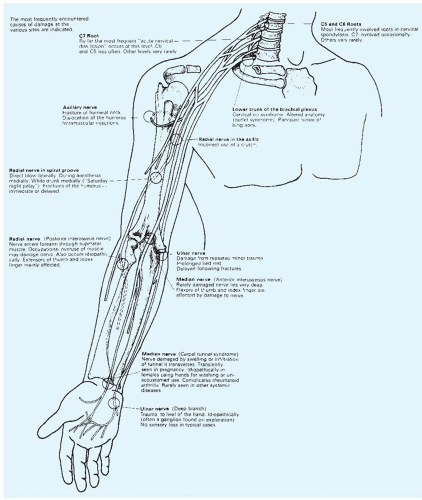

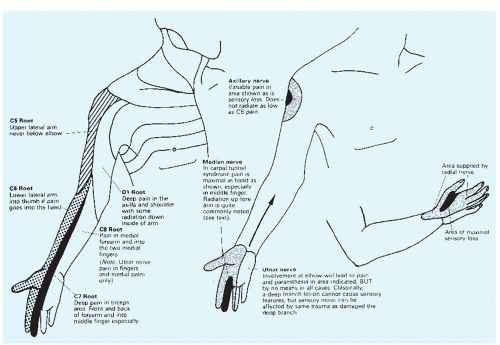

Age-related desiccation of cervical disks leads to increased stress on the vertebral bodies. Osteophytic spurs develop and may encroach on nerve roots. More serious but less common is encroachment on the spinal cord itself by progressive cervical spondylotic changes. Usually, a combination of radiculopathy involving the C5, C6, or C7 roots (Figs. 167-1 and 167-2) and myelopathy is present. Cord compression resulting from spondylosis is indicated by radicular pain, variable weakness, diminished reflexes, and atrophy in the arms, with spastic weakness and hyperreflexia in the lower extremities.

Radiologic assessment typically includes cervical spinal MRI. Unfortunately, nearly 50% of patients older than age 50 years show degenerative changes of the cervical spine on plain radiographic films, and these do not correlate well with the degree of abnormality found clinically in either radiculopathy or myelopathy. Limiting MRI ordering to instances when radicular pain is severe or when a motor or sensory deficit, reflex change, or myelopathic finding is present makes for more cost-effective use.

It may be difficult to distinguish cervical spondylotic myelopathy from other progressive myelopathies, which include multiple sclerosis, subacute combined degeneration associated with vitamin B12 or copper deficiency, spinal tumor, and syringomyelia. Suspicion of myelopathy should prompt referral to a neurologist.

Brachial Plexus Neuritis.

Brachial plexus neuritis, a painfully disabling condition, develops in some patients after an immunization or viral infection and in others without any antecedent illness. It presents with severe pain in the shoulder and upper arm followed by weakness. Usually, the upper roots of the plexus are involved more than the lower ones. The prognosis is ultimately good, but recovery may be prolonged. Infiltration of the plexus by tumor or progressive, often painless dysfunction due to radiation-related injury should be suspected in patients with appropriate antecedent history.

Clinical examination reveals variable weakness and sensory loss in the C5 to T1 root distributions (Fig. 167-2) with diminished deep tendon reflexes. Because many nerve roots are involved, confusion with a cervical disk problem does not usually arise. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies help to localize the abnormality. MRI of the brachial plexus with gadolinium enhancement may be valuable in excluding neoplastic disease of the plexus.

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.

A cervical rib or bony abnormality of the first rib may cause pressure on the subclavian artery or brachial plexus as it passes through the thoracic outlet (Fig. 167-1). The diagnosis is primarily clinical and is based on the presence of pain in the arm in certain positions, color changes in the hand, and a pattern of sensory loss and weakness most pronounced in the fourth and fifth fingers. Deep tendon reflexes are usually normal. A bruit may be heard over the subclavian artery. The differential diagnosis includes Raynaud phenomenon, ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow, and compression of the brachial plexus by neoplasm or fibrosis resulting from radiation

Most surgeons advocate removal of the potentially constricting structures (cervical rib, fascial band to first rib, or first rib). Shoulder exercises to improve posture are often advised first, and orthopedic advice should be sought in each case.

Long Thoracic Nerve Entrapment.

This nerve arises from the brachial plexus and innervates the serratus anterior. It is vulnerable to injury in workers who lift or push heavy loads, occurs after direct trauma from heavy backpacks, and may evolve for several months after the injury. The patient notes a change in the appearance of the shoulder, and examination reveals winging of the scapula. Most cases have a good prognosis.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.

In this disorder, the median nerve is entrapped at the carpal tunnel (Fig. 167-1) because of pressure from ligamentous thickening. Most cases are idiopathic, but the disorder may be seen with rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, acromegaly, hypothyroidism, fractures of the carpal bones, amyloidosis, and myeloma. Occupational causes involving repetitive traumatic actions have been implicated. A combination of pain, paresthesias, and numbness in the hand, forearm, or sometimes whole arm is characteristic, and symptoms are often worse at night (Fig. 167-2). Later, muscle weakness (particularly of thumb abduction and opposition) occurs, and thenar atrophy may be seen.

Tapping on the wrist or anywhere else along the median nerve may reproduce the pain (Tinel sign). The differential diagnosis includes radiculopathy from cervical spine disease, but the exact location of the pain should conform to the median nerve rather than to the distribution of just one nerve root.

EMG and nerve conduction studies with motor and sensory conduction latencies of the median nerve provide the most useful data. Initial symptom relief may be obtained with nocturnal wrist splints. Surgical intervention is usually successful.

EMG and nerve conduction studies with motor and sensory conduction latencies of the median nerve provide the most useful data. Initial symptom relief may be obtained with nocturnal wrist splints. Surgical intervention is usually successful.

Ulnar Nerve Entrapment.

The most common location of ulnar entrapment is the elbow (Fig. 167-1). Causes include fracture deformities, arthritis, faulty positioning of the arm during surgery, or repetitive occupational or recreational trauma (e.g., tennis, string instrument playing). Sensation is usually spared in the forearm, but sensory loss occurs in the fifth finger and half of the fourth (Fig. 167-2). Wasting of the intrinsic muscles of the hand with weakness of grip occurs later. Nerve conduction studies can accurately localize the site of compression. If focal entrapment is present, repositioning of the nerve or elbow

synovectomy may be necessary, but patients with trauma, diabetes, or the so-called “tardy” ulnar palsies (dysfunction developing late after injury) may not improve.

synovectomy may be necessary, but patients with trauma, diabetes, or the so-called “tardy” ulnar palsies (dysfunction developing late after injury) may not improve.

Radial Nerve Injuries.

Compression of the radial nerve most often occurs in the axilla or upper arm. It may be caused by improperly used crutches, prolonged pressure during sleep (the “Saturday night” palsy), or direct injury. Extensors of the arm, wrist, and fingers are differentially affected depending on the level of compression. With lesions above the spiral groove, the triceps muscle will be weak, while lesions below the spiral groove spare triceps and affect wrist and finger extensors.

Lower Extremity Syndromes

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve Compression.

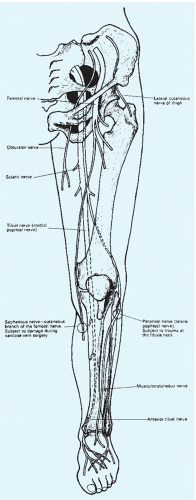

Also known as meralgia paresthetica, this syndrome involves a nerve formed by branches arising from the second and third lumbar roots. The nerve enters the thigh in close relation to the inguinal ligament, the anterior superior iliac spine, and the sartorius muscle insertion (Fig. 167-3). It is purely sensory and supplies the anterolateral and lateral aspects of the thigh almost as far as the knee (Fig. 167-4). Compression causes an extremely unpleasant, characteristic burning pain with increased cutaneous sensitivity. Sitting or lying usually provides relief, but standing or walking exacerbates the pain. The syndrome often occurs in obesity, in pregnancy, or when tight corsets are worn. It is more common in diabetics. The neuropathy tends to regress spontaneously, but weight loss should be encouraged.

The differential diagnosis includes a lesion of the second or third lumbar roots, usually associated with low back pain radiating into the lower leg and with sensory changes that extend further down the leg and more medially. Iliopsoas or quadriceps weakness is present with lumbar root problems, but weakness and reflex changes do not occur in meralgia paresthetica.

Femoral Neuropathy.

The femoral nerve derives from the second, third, and fourth lumbar roots. Its posterior division is the major innervation to the quadriceps and terminates as the saphenous nerve, which supplies sensation to the medial aspect of the leg as far as the medial malleolus (Fig. 167-3). The onset of femoral neuropathy is frequently sudden and painful and is followed quickly by wasting and weakness in the quadriceps, loss of knee jerk, and sensory impairment over the anteromedial thigh (Fig. 167-4). If marked hip flexion weakness is also present, the site of the lesion is usually in the lumbar plexus. Sensory symptoms in the saphenous distribution are uncommon in lesions of the main trunk of the femoral nerve.

Entrapment may occur in the inguinal region and from direct retroperitoneal compression by tumor or hematoma; however, the most common cause of femoral nerve injury is diabetes, presumably from diabetic nerve infarction causing thigh pain, weakness, and sensory deficit. Electromyographically, the involvement in diabetic femoral neuropathy is frequently more widespread. Although some improvement may occur, the patient is often left quite weak.

Sciatic Nerve Syndromes.

The sciatic nerve arises from the lumbosacral plexus (L4 through S3) and terminates in the common peroneal and tibial nerves (Fig. 167-3). The tibial nerve supplies the gastrocnemius, plantaris, soleus, and popliteus muscles, and its extension into the calf, the posterior tibial nerve, supplies muscles of the calf. All of these muscles are involved in plantar flexion. The common peroneal nerve divides into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves. The latter supplies the muscles of

dorsiflexion of the foot and toes. The superficial peroneal nerve innervates the muscles that evert the foot.

dorsiflexion of the foot and toes. The superficial peroneal nerve innervates the muscles that evert the foot.

Sciatic nerve compression may result from tumors within the pelvis or from prolonged sitting or lying on the buttocks. Gluteal abscesses and misplaced buttock injections have caused sciatic injury. Weakness of the gluteal muscles and pain in the area of the sciatic notch imply compression within the pelvis. Lesions just beyond the sciatic notch cause weakness in the hamstrings and in all the muscles of the lower leg.

Common peroneal compression usually occurs at the level of the fibular head (Fig. 167-3) and is seen in cachectic patients following prolonged bed rest, alcoholics, diabetics, and patients placed in tight casts. Injury leads to faulty dorsiflexion and eversion of the foot, which produces a characteristic foot drop with a slapping gait. Complete or partial recovery can be expected when paralysis results from transient pressure. Treatment consists of a foot brace and careful avoidance of compressive positions.

Lumbar Disk Syndromes.

Compressive neuropathies of the lower limbs must be distinguished from the very common lumbar disk syndromes. In the lumbar region, the fourth and fifth disks are most frequently affected (i.e., the disks between the L4 and L5 vertebral bodies and between the L5 and S1 vertebrae). The most common complaint is the onset of severe low back pain (see Chapter 147). The inciting event is often trivial, although heavy lifting or an acute twisting motion is sometimes reported. The pain is worsened by bending forward, sneezing, or straining.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree