CHAPTER 140

Fishhook Removal

Presentation

The patient has been snagged with a fishhook and arrives with it embedded in the skin (Figure 140-1). This most commonly occurs on the hand, face, scalp, or upper extremity but can involve any body part. Structures deep to the skin and subcutaneous tissue are usually not involved.

Figure 140-1 Fishhook impalement.

What To Do:

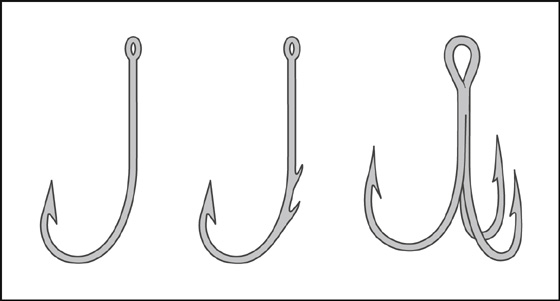

Inquire about or examine to see the type of hook involved. Is it a single or treble (multiple) hook, and does it have a single barb or multiple barbs (Figure 140-2)?

Inquire about or examine to see the type of hook involved. Is it a single or treble (multiple) hook, and does it have a single barb or multiple barbs (Figure 140-2)?

Figure 140-2 Examples of various hooks and barbs.

All items attached to the hook (i.e., fishing line, bait, and the body of any lure) should be removed.

All items attached to the hook (i.e., fishing line, bait, and the body of any lure) should be removed.

Radiographs are generally not required or helpful but may aid in determining the type of fishhook and depth of penetration in difficult cases or if patient is unsure of the type of hook.

Radiographs are generally not required or helpful but may aid in determining the type of fishhook and depth of penetration in difficult cases or if patient is unsure of the type of hook.

Any fishhook injury that may involve deeper structures, such as bone tendons, vessels, nerves, or joints, may benefit from a specialist consultation.

Any fishhook injury that may involve deeper structures, such as bone tendons, vessels, nerves, or joints, may benefit from a specialist consultation.

Patients with fishhooks that are imbedded in the eye or in a location in which removal may injure the eye should have the eye covered with a protective metal shield. With an eye injury, an ophthalmologist should be immediately consulted.

Patients with fishhooks that are imbedded in the eye or in a location in which removal may injure the eye should have the eye covered with a protective metal shield. With an eye injury, an ophthalmologist should be immediately consulted.

For uncomplicated cases, cleanse the hook and wound with povidone-iodine or another antiseptic solution.

For uncomplicated cases, cleanse the hook and wound with povidone-iodine or another antiseptic solution.

Provide tetanus prophylaxis as needed (see Appendix H).

Provide tetanus prophylaxis as needed (see Appendix H).

Most patients will benefit from slowly administered local infiltration of 1% buffered lidocaine using a 27-gauge needle inserted through the same puncture created by the fishhook.

Most patients will benefit from slowly administered local infiltration of 1% buffered lidocaine using a 27-gauge needle inserted through the same puncture created by the fishhook.

After local anesthesia, children can usually be successfully treated by using verbal distraction and hiding the procedure from their view. When cooperation cannot be obtained, consider procedural sedation and analgesia (see Appendix E).

After local anesthesia, children can usually be successfully treated by using verbal distraction and hiding the procedure from their view. When cooperation cannot be obtained, consider procedural sedation and analgesia (see Appendix E).

Fishhooks with more than one point (e.g., treble fishhooks) should have the uninvolved points taped or cut off to avoid embedding these during removal. If more than one point of a treble hook is embedded in the skin, use an orthopedic pin cutter to snap the shaft of the treble hook, thereby separating it into multiple single hooks. The following standard techniques can then be used.

Fishhooks with more than one point (e.g., treble fishhooks) should have the uninvolved points taped or cut off to avoid embedding these during removal. If more than one point of a treble hook is embedded in the skin, use an orthopedic pin cutter to snap the shaft of the treble hook, thereby separating it into multiple single hooks. The following standard techniques can then be used.

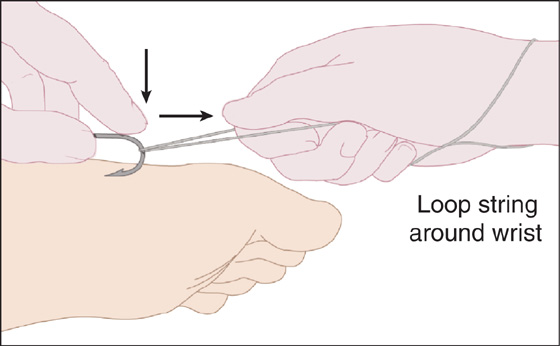

For hooks lodged superficially, first try the simple “retrograde” technique. Push the hook back along the entrance pathway while applying gentle downward pressure on the shank (like the “string” technique, without the string) (Figure 140-3).

For hooks lodged superficially, first try the simple “retrograde” technique. Push the hook back along the entrance pathway while applying gentle downward pressure on the shank (like the “string” technique, without the string) (Figure 140-3).

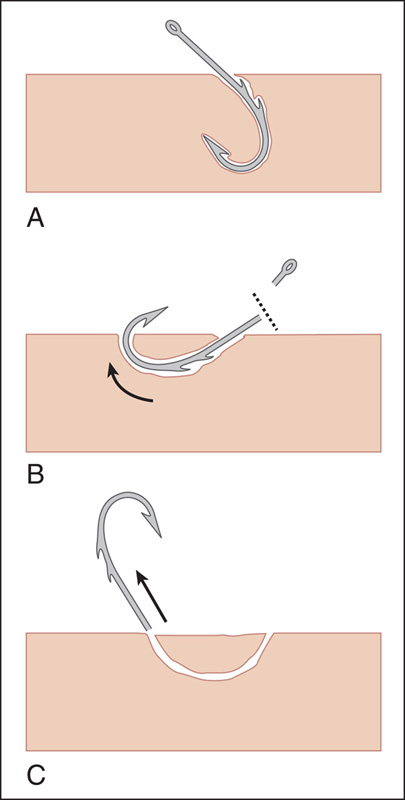

Figure 140-3 “String” technique.

If the hook does not come out, an 18-gauge needle may be inserted into the puncture hole and used as a miniature scalpel blade. A No. 11 scalpel blade can then be used to slightly enlarge the puncture wound for easier removal, if needed. Manipulate the hook into such a position that you can cut the bands of connective tissue caught over the barb and release it.

If the hook does not come out, an 18-gauge needle may be inserted into the puncture hole and used as a miniature scalpel blade. A No. 11 scalpel blade can then be used to slightly enlarge the puncture wound for easier removal, if needed. Manipulate the hook into such a position that you can cut the bands of connective tissue caught over the barb and release it.

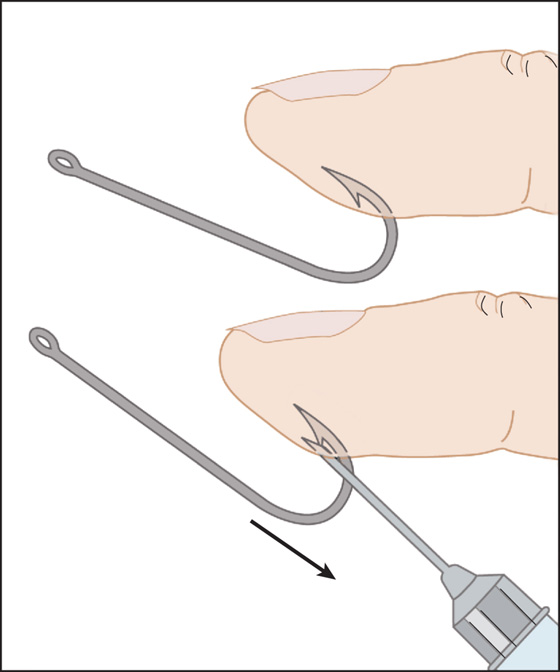

For more deeply embedded hooks, “needling” the hook is an alternative technique that requires somewhat greater skill but allows work on an unstable skin surface, such as a finger or ear (Figure 140-4). Slide a large-gauge (No. 20 or 18) hypodermic needle through the puncture wound alongside the hook. Now blindly slide the needle opening over the barb of the hook and, holding the hook firmly, lock the two together. With the barb covered, remove the hook and needle as one unit. Because the needle does not cut through the dermis, there is often no need for local anesthesia, although when available, most patients still appreciate getting it. When anesthesia is used, this technique can be made easier by slightly enlarging the entrance wound with a No. 11 scalpel blade.

For more deeply embedded hooks, “needling” the hook is an alternative technique that requires somewhat greater skill but allows work on an unstable skin surface, such as a finger or ear (Figure 140-4). Slide a large-gauge (No. 20 or 18) hypodermic needle through the puncture wound alongside the hook. Now blindly slide the needle opening over the barb of the hook and, holding the hook firmly, lock the two together. With the barb covered, remove the hook and needle as one unit. Because the needle does not cut through the dermis, there is often no need for local anesthesia, although when available, most patients still appreciate getting it. When anesthesia is used, this technique can be made easier by slightly enlarging the entrance wound with a No. 11 scalpel blade.

Figure 140-4 Needling hook.

When a single hook is embedded in a stable skin surface, such as the back, scalp, or arm, the best way to remove it is by using a simple “string” or “string-yank” technique (see Figure 140-3). Align the shaft of the hook so that it is parallel to the skin surface. Press down on the hook with the index finger to disengage the barb. Place a loop of string (fishing line or 1-0 silk) over the wrist and around the hook, and with a quick jerk opposite from the direction in which the shaft of the hook is running, pop the hook out. When done properly, this procedure is painless and does not require anesthesia. The hook may shoot out in the direction that the string is being pulled; so, be careful that no one is standing in the path of the fishhook, and use protective eyewear.

When a single hook is embedded in a stable skin surface, such as the back, scalp, or arm, the best way to remove it is by using a simple “string” or “string-yank” technique (see Figure 140-3). Align the shaft of the hook so that it is parallel to the skin surface. Press down on the hook with the index finger to disengage the barb. Place a loop of string (fishing line or 1-0 silk) over the wrist and around the hook, and with a quick jerk opposite from the direction in which the shaft of the hook is running, pop the hook out. When done properly, this procedure is painless and does not require anesthesia. The hook may shoot out in the direction that the string is being pulled; so, be careful that no one is standing in the path of the fishhook, and use protective eyewear.

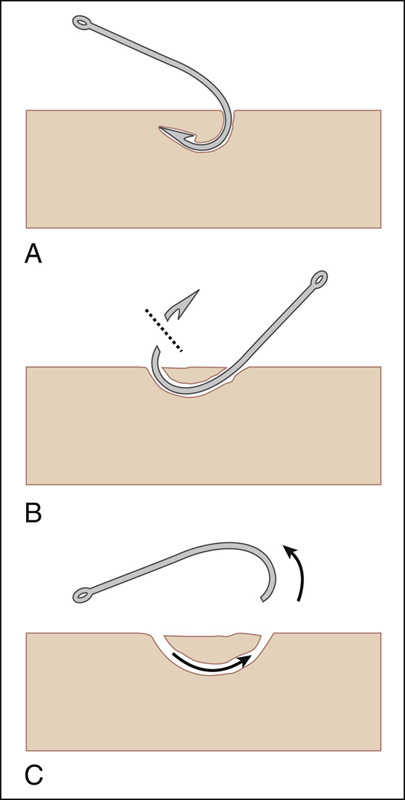

When the hook is deeply embedded, the barbed end of the hook is protruding through the skin, or the previous techniques cannot be used, proceed with the “push through” maneuver. Locally infiltrate the area with 1% buffered lidocaine. Then, using pliers or a needle holder, push the point of the hook along with its barb up through the skin. When dealing with a single-barbed hook, use an orthopedic pin cutter or metal snip to cut off the tip of the hook and remove the shaft (Figure 140-5); with a multiple-barbed hook, cut off the shaft of the hook and pull the tip through (Figure 140-6). To help push the tip of the hook up through the skin when the skin is tenting, you can place the open end of a 3- or 5-mL syringe barrel (with the plunger removed) over the tenting skin to provide downward countertraction.

When the hook is deeply embedded, the barbed end of the hook is protruding through the skin, or the previous techniques cannot be used, proceed with the “push through” maneuver. Locally infiltrate the area with 1% buffered lidocaine. Then, using pliers or a needle holder, push the point of the hook along with its barb up through the skin. When dealing with a single-barbed hook, use an orthopedic pin cutter or metal snip to cut off the tip of the hook and remove the shaft (Figure 140-5); with a multiple-barbed hook, cut off the shaft of the hook and pull the tip through (Figure 140-6). To help push the tip of the hook up through the skin when the skin is tenting, you can place the open end of a 3- or 5-mL syringe barrel (with the plunger removed) over the tenting skin to provide downward countertraction.

Figure 140-5 Advance and cut method: single-barbed fishhook.

Figure 140-6 Advance and cut method: multiple-barbed fishhook.

After the hook is removed, cleanse the wound with povidone-iodine solution and remove any debris (e.g., bait).

After the hook is removed, cleanse the wound with povidone-iodine solution and remove any debris (e.g., bait).

Prophylactic antibiotic therapy is generally not necessary but may be considered for persons who are immunosuppressed or have injuries that involve tendons, cartilage, joints, or bone.

Prophylactic antibiotic therapy is generally not necessary but may be considered for persons who are immunosuppressed or have injuries that involve tendons, cartilage, joints, or bone.

Provide follow-up in 2 days for high-risk patients. Provide immediate follow-up care for any patient who develops signs or symptoms of infection (rare).

Provide follow-up in 2 days for high-risk patients. Provide immediate follow-up care for any patient who develops signs or symptoms of infection (rare).

What Not To Do:

Do not try to remove a multiple-barbed hook or fishing lure without first removing or covering the free hooks.

Do not try to remove a multiple-barbed hook or fishing lure without first removing or covering the free hooks.

Do not attempt to use the “string” technique if the hook is near the patient’s eye.

Do not attempt to use the “string” technique if the hook is near the patient’s eye.

Do not routinely prescribe prophylactic antibiotics. Even hooks that have been contaminated by fish rarely cause secondary infection.

Do not routinely prescribe prophylactic antibiotics. Even hooks that have been contaminated by fish rarely cause secondary infection.

Discussion

In places with crowded fishing conditions, and especially in areas where fly fishing is popular, fishhook injuries are not uncommon because of the volume of anglers.

Most embedded fishhooks can be removed with minimal surgical intervention. In general, the retrograde and string-yank methods should be the first techniques attempted, because they result in the least amount of tissue trauma. The more invasive procedures, such as the advance and cut techniques, usually are reserved for more difficult cases. Sometimes multiple techniques must be attempted before the fishhook is successfully removed.

With the string, retrograde, and needling techniques, there is no lengthening of the puncture track or creation of an additional puncture wound. The quickest and easiest method for removing a fishhook is the string technique. Use it in the field with no special equipment or anesthesia. It is not recommended, however, when the hook is positioned on a skin surface that is likely to move when the string is pulled. The skin movement may cause the vector forces to change, and therefore the barb may not release.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree