CHAPTER 139

Fingertip Avulsion, Superficial

Presentation

The mechanisms of injury can be diverse: a knife, a meat slicer, a closing door, broken glass, spinning fan blades, or turning gears. Depending on the angle of the amputation, varying degrees of tissue loss will occur from the volar pad or the fingertip.

What To Do:

Determine the exact mechanism of injury and inquire as to the patient’s hand dominance, age and skeletal maturity, occupation and hobbies, length of time since the injury, prior hand injuries or surgery, and tetanus immunization status.

Determine the exact mechanism of injury and inquire as to the patient’s hand dominance, age and skeletal maturity, occupation and hobbies, length of time since the injury, prior hand injuries or surgery, and tetanus immunization status.

Examine the injury to determine whether it is a crush versus a sharp injury, whether there is an associated nail or nail bed injury (see Chapter 146), or whether there is bone involvement.

Examine the injury to determine whether it is a crush versus a sharp injury, whether there is an associated nail or nail bed injury (see Chapter 146), or whether there is bone involvement.

Obtain a radiograph of any crush injury or an injury caused by a high-speed mechanical instrument, such as a hedge trimmer or lawn mower.

Obtain a radiograph of any crush injury or an injury caused by a high-speed mechanical instrument, such as a hedge trimmer or lawn mower.

Provide tetanus prophylaxis when indicated (see Appendix H).

Provide tetanus prophylaxis when indicated (see Appendix H).

Wounds that are infected; associated with tendon injuries; associated with fractures (other than tuft fractures); show exposed bone, accompanied by digit dislocations; as well as wounds greater than 1 cm with absent, destroyed, or heavily contaminated tissue, require specialty consultation with a hand surgeon.

Wounds that are infected; associated with tendon injuries; associated with fractures (other than tuft fractures); show exposed bone, accompanied by digit dislocations; as well as wounds greater than 1 cm with absent, destroyed, or heavily contaminated tissue, require specialty consultation with a hand surgeon.

With larger wounds that do not require specialty consultation, perform a digital block to obtain complete anesthesia (see Appendix B).

With larger wounds that do not require specialty consultation, perform a digital block to obtain complete anesthesia (see Appendix B).

Thoroughly débride and irrigate the wound. Uncontaminated wounds secondary to sharp amputations require only a gentle cleansing with saline or an equivalent agent.

Thoroughly débride and irrigate the wound. Uncontaminated wounds secondary to sharp amputations require only a gentle cleansing with saline or an equivalent agent.

When active bleeding is present, provide a bloodless field by wrapping the finger from the tip proximally with a Penrose drain. Secure the proximal portion of this wrap with a hemostat and unwrap the tip of the finger. Alternatively, cut the tip off a small-sized surgical glove finger; place the glove over the hand, then roll the cut end down over the injured finger, forming a constricting band. A commercial digital tourniquet (Turnicot) may also be used.

When active bleeding is present, provide a bloodless field by wrapping the finger from the tip proximally with a Penrose drain. Secure the proximal portion of this wrap with a hemostat and unwrap the tip of the finger. Alternatively, cut the tip off a small-sized surgical glove finger; place the glove over the hand, then roll the cut end down over the injured finger, forming a constricting band. A commercial digital tourniquet (Turnicot) may also be used.

For wounds with less than 1 sq cm of full-thickness tissue loss, you may allow the injury to granulate. A small patch of hemostatic gauze (Surgicel, ActCel, GuardaCare) or foam (Gelfoam) can be applied (following thorough irrigation) to reduce further bleeding. A simple nonadherent dressing (see Appendix C) with some gentle compression can then be applied.

For wounds with less than 1 sq cm of full-thickness tissue loss, you may allow the injury to granulate. A small patch of hemostatic gauze (Surgicel, ActCel, GuardaCare) or foam (Gelfoam) can be applied (following thorough irrigation) to reduce further bleeding. A simple nonadherent dressing (see Appendix C) with some gentle compression can then be applied.

If there is greater than 1 sq cm of full-thickness skin loss and there is no exposed bone, there are three options that may be followed after surgical consultation.

If there is greater than 1 sq cm of full-thickness skin loss and there is no exposed bone, there are three options that may be followed after surgical consultation.

Simply apply the same nonadherent dressing used for a smaller wound. (Use the hemostatic gauze or foam only at the discretion of the hand surgeon.)

Simply apply the same nonadherent dressing used for a smaller wound. (Use the hemostatic gauze or foam only at the discretion of the hand surgeon.)

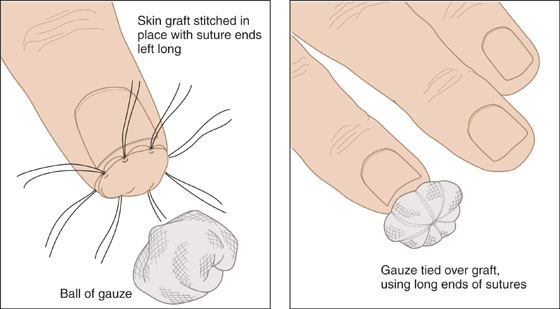

If the avulsed piece of tissue is available and is not severely crushed or contaminated, convert it into a modified full-thickness graft and suture it in place. Any adherent fat and as much cornified epithelium as possible must be cut and scraped away using a scalpel blade. This will produce a thinner, more pliable graft that will have much less tendency to lift off its underlying granulation bed as the cornified epithelium dries and contracts. Leaving long ends on the sutures will allow a compressive pad of an overlying moistened cotton bolus to be tied on and will help prevent fluid accumulation under the graft (Figure 139-1). A simple fingertip compression dressing (e.g., Tubegauze) can serve the same purpose.

If the avulsed piece of tissue is available and is not severely crushed or contaminated, convert it into a modified full-thickness graft and suture it in place. Any adherent fat and as much cornified epithelium as possible must be cut and scraped away using a scalpel blade. This will produce a thinner, more pliable graft that will have much less tendency to lift off its underlying granulation bed as the cornified epithelium dries and contracts. Leaving long ends on the sutures will allow a compressive pad of an overlying moistened cotton bolus to be tied on and will help prevent fluid accumulation under the graft (Figure 139-1). A simple fingertip compression dressing (e.g., Tubegauze) can serve the same purpose.

Figure 139-1 Simple fingertip compression dressing.

When there is a large area of tissue loss that has been thoroughly cleaned and débrided, and the avulsed portion has been lost or destroyed and there is no exposed bone, consider a thin split-thickness skin graft on the site. This option should only be pursued after consultation with a hand specialist. Using buffered 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) containing 1:100,000 epinephrine, raise an intradermal wheal on the volar aspect of the patient’s wrist or hypothenar eminence until it is the size of a quarter. Then, using a No. 10 scalpel blade, slice off a very thin graft from this site. Apply the graft in the same manner as the full-thickness one (described earlier) with a compression dressing.

When there is a large area of tissue loss that has been thoroughly cleaned and débrided, and the avulsed portion has been lost or destroyed and there is no exposed bone, consider a thin split-thickness skin graft on the site. This option should only be pursued after consultation with a hand specialist. Using buffered 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) containing 1:100,000 epinephrine, raise an intradermal wheal on the volar aspect of the patient’s wrist or hypothenar eminence until it is the size of a quarter. Then, using a No. 10 scalpel blade, slice off a very thin graft from this site. Apply the graft in the same manner as the full-thickness one (described earlier) with a compression dressing.

In infants and young children (younger than 2 years), fingertip amputations can be sutured back on in their entirety as a composite graft (i.e., containing more than one type of tissue). If the amputated tissue is contaminated or not available, the wound can usually be dressed and allowed to granulate.

In infants and young children (younger than 2 years), fingertip amputations can be sutured back on in their entirety as a composite graft (i.e., containing more than one type of tissue). If the amputated tissue is contaminated or not available, the wound can usually be dressed and allowed to granulate.

In older children and adults, composite grafts will usually fail, and therefore it is important to consult your hand surgeon before any repair is attempted.

In older children and adults, composite grafts will usually fail, and therefore it is important to consult your hand surgeon before any repair is attempted.

When the loss of soft tissue has been sufficient to expose bone, simple grafting will be unsuccessful, and surgical consultation is required.

When the loss of soft tissue has been sufficient to expose bone, simple grafting will be unsuccessful, and surgical consultation is required.

Schedule a wound check in 2 days. During that time, the patient should be instructed to keep his finger elevated to the level of his heart or above, and maintained at rest.

Schedule a wound check in 2 days. During that time, the patient should be instructed to keep his finger elevated to the level of his heart or above, and maintained at rest.

Apply a protective aluminum splint for comfort (see Chapter 111).

Apply a protective aluminum splint for comfort (see Chapter 111).

Unless the bandage gets wet, a dressing change need not be done for 5 to 7 days, at which time the cotton bolster dressing can be removed and active range of motion begun.

Unless the bandage gets wet, a dressing change need not be done for 5 to 7 days, at which time the cotton bolster dressing can be removed and active range of motion begun.

Always have the patient return immediately if there is increasing pain, purulent drainage, red streaking extending from wound, or other signs of infection.

Always have the patient return immediately if there is increasing pain, purulent drainage, red streaking extending from wound, or other signs of infection.

If the wound is contaminated, a 3- to 5-day course of an antibiotic, such as cephalexin (Keflex), 500 mg qid, may be effective prophylaxis, but antibiotics are not routinely required, even for an uncomplicated, open phalanx-tip fracture.

If the wound is contaminated, a 3- to 5-day course of an antibiotic, such as cephalexin (Keflex), 500 mg qid, may be effective prophylaxis, but antibiotics are not routinely required, even for an uncomplicated, open phalanx-tip fracture.

Recommend an analgesic, such as acetaminophen, and, if needed, prescribe a narcotic, such as hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Lorcet, Vicodin), 5 to 10 mg q4h prn for pain.

Recommend an analgesic, such as acetaminophen, and, if needed, prescribe a narcotic, such as hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Lorcet, Vicodin), 5 to 10 mg q4h prn for pain.

What Not To Do:

Do not apply a graft directly over bone or over a potentially devitalized or contaminated bed.

Do not apply a graft directly over bone or over a potentially devitalized or contaminated bed.

Do not attempt to stop wound bleeding by cautery or ligature, measures that are likely to increase tissue damage and are probably unnecessary.

Do not attempt to stop wound bleeding by cautery or ligature, measures that are likely to increase tissue damage and are probably unnecessary.

Do not forget to remove any constricting tourniquet used to obtain a bloodless field. This may lead to ischemic autoamputation.

Do not forget to remove any constricting tourniquet used to obtain a bloodless field. This may lead to ischemic autoamputation.

Discussion

The fingertip, the most distal portion of the hand, is the most susceptible to injury and thus the most often injured part. Treating small- and medium-sized fingertip amputations without grafting is appropriate in most cases. Allowing repair by wound contracture may leave the patient with as good a result and likely better sensation, without the discomfort or minor disfigurement of a split-thickness graft. This open technique is not recommended for wounds greater than 1 cm, because healing time will exceed 3 to 4 weeks, and it will significantly delay return to work. A potential complication of this technique includes loss of volume and fingertip pulp.

Skin grafting may allow the patient more use of his or her finger and less sensitivity at the injury site. This technique should only be undertaken by experienced providers after discussion with a hand specialist. The full-thickness graft will give an early tough cover that is insensitive but is more durable and has a more normal appearance. Unlike the full-thickness graft, a thin split-thickness graft will allow wound contracture and thereby allow skin with normal sensitivity to be drawn over the end of the finger, resulting in a smaller defect.

The nature of the wound, the preferences of the follow-up physician, and the special occupational and emotional needs of the patient should determine the technique followed. Explain the options to the patient, who can help decide the course of action.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree