Chapter 5 Fibromyalgia and hypermobility

Introduction

Within the definition of CWP lies the phenomenon fibromyalgia (FM) (Wolfe et al 1990). Equally, joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS) (Chapter 1) may present as widespread pain of a chronic nature, or indeed as regional pain.

Chronic widespread pain

Prevalence

From large population surveys the prevalence of CWP is approximately 11% and CRP 25% (Croft et al 1993, Bergman et al 2001). Bergman’s community study of over 1800 people in southern Sweden over a period of 3 years demonstrated that these figures were constant over time in this population but that individual’s pain patterns changed. It was noted that 76 individuals went from CRP to CWP and 64 moved in the other direction. Furthermore 222 moved from having no chronic pain to either CRP or CWP while 201 moved from CWP or CRP to no chronic pain (Bergman et al 2002).

CWP is a symptom, not a disease. That it truly is common in the general population without having identified disease or bias by focusing attention on those who seek health advice is perhaps best seen in the study carried out by Wolfe et al (1995) in Wichita, Kansas. Here, a postal questionnaire about pain was sent to households selected randomly from a directory of addresses. Among 3000 individuals who returned data, the prevalence of CWP was 10.6% and that of CRP, 20.1%; remarkably similar to earlier studies.

Patients with CWP often have poor health and reduced quality of life. Croft et al (1993) showed strong associations between the presence of CWP and fatigue and depression. A number of other studies have looked at the factors that influence development and/or persistence of CWP (Buskila et al 2000, McBeth et al 2001a, 2001b, Bergman et al 2002) and have shown that many of these factors are psychosocial and not related to any particular organic or physical process that causes the pain. This does not mean that the pain suffered by patients with CWP is any less real and distressing than that suffered by patients with, for example, rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis.

Fibromyalgia

Developing the concept

The fact that many patients present with widespread pain apparently emanating from soft tissues, but with no specific or readily diagnosable cause, has been recognized for many years. The clinical picture has been given various names, including fibrositis. In the mid 1970s, Moldofsky et al (1975) carried out electroencephalography (EEG) readings during sleep in patients with this clinical picture, and concluded that they showed a specific pattern – the alpha-delta pattern. It was also reported that a similar pattern could be induced in healthy adults who were deprived of non-rapid-eye-movement sleep and proposed that it might result from abnormalities in serotonin balance in the brain (Moldofsky & Scarisbrick 1976). They termed chronic pain with sleep disturbance and alpha-delta EEG pattern ‘fibrositis syndrome’. Others were to use the term FM to describe such patients. There was, however, no universally accepted definition for FM, making it difficult to carry out robust prevalence studies or clinical trials.

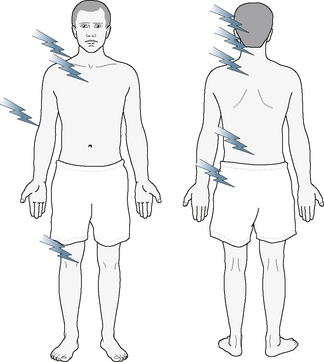

Thus, in the late 1980s, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) assembled a multicentre group to carry out a study to establish diagnostic criteria for FM (Wolfe et al 1990). The group reached consensus as to which clinical data should be gathered from each subject in the study including the sites at which the soft tissues should be palpated for tenderness. It emerged that two criteria were necessary to make a diagnosis with a sensitivity of 88.4% and specificity of 81.1%. These criteria were:

Fig. 5.1 Distribution of tender points in fibromyalgia.

There are nine sites repeated on both sides to give a maximum score of 18.

Reproduced with permission of the author (Hakim 2009)

Fibromyalgia: The size of the problem

Once thought to be a nearly random assortment of unverifiable signs and symptoms, FM has emerged as a diagnosable and regrettably common disorder. It is recognized by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), U.S. Social Security Agency, U.S. Veteran’s Administration, U.S. Federal Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMEA) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Given a prevalence of 2% in the United States, 4.7% in Europe (Branco et al 2008) and increased awareness worldwide, FM is now a major health burden for both the individual and society at large (White et al 1999, Penrod et al 2004, Berger et al 2007, Hoffman & Dukes 2008). In 2005, the cost of FM per patient ($10,199/year) was nearly equal that of osteoarthritis (White et al 2008).

In a British group of 72 patients with FM followed for a median of 4 years, 97% continued to have symptoms of pain, tiredness and/or lethargy, 85% still had multiple tender points and 60% felt worse at follow-up than at presentation (Ledingham et al 1993). Half the patients had stopped work due to their illness and 32% described themselves as being heavily dependent. These results are consistent with those of other groups. Wolfe et al (1995) showed that there was a strong correlation between FM and applications for disability benefits, and 62% of a Swedish population with FM required such benefits (Burckhardt et al 1994). In a large study using records from the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database, Hughes et al (2006) compared 2260 patients with a recorded new diagnosis of FM with non-FM controls (ten controls per case). They found that patients with FM had significantly higher rates of clinical visits, prescriptions and diagnostic tests than the control group from at least 10 years prior to the diagnosis being made.

The association with hypermobility and joint hypermobility syndrome

In routine clinical practice, FM is usually explained to patients as a condition in which the muscles become tense, tender and tight due to lack of relaxation, often secondary to a poor sleep pattern and chronic tiredness. Combining a demonstration of tender points with an explanation that this is diagnostic for FM is a powerful approach to showing a patient that the apparently inexplicable chronic pain condition actually has a reasonable and well-recognized explanation. This can reduce fear of the unknown and enables those engaged in treatment to advise the patient about what is likely to happen in the future. Although the pain is not likely to disappear completely one can be clear in advising that this syndrome does not lead to joint destruction or deformity and that the patient is not likely to need surgery or powerful drugs like corticosteroids or immunosuppressants. Furthermore, as outlined in the recent EULAR guidelines (Carville et al 2008), there are a range of different types of treatment that can be offered to alleviate some of the symptoms (Chapter 7).

If the pain of FM arises from tension and tenderness in muscles and soft tissues it would be reasonable to suppose that some patients with JHM (Fitzcharles 2000) or JHS might be prone to developing FM.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree